Demolished viaducts

Demolished viaducts

They were erected through grit, determination and ingenuity, costing serious money and all-too-often lives. Each demanded many months of toil. But their demise, after the railway had done with them, sometimes took just moments.

Although many of our finest viaducts are now afforded legal protection, a great many others linger only in the memory and on faded photos, having been sacrificed at the respective altars of health ‘n’ safety and blinkered economics.

This page will recall some of the grandest structures to be stolen from the landscape since the railway’s reshaping of the Fifties and Sixties.

Crowhurst Viaduct

A product of the Crowhurst Sidley & Bexhill Railway, the 17-arch Crowhurst (aka Filsham, Sidley and Combe Haven) Viaduct was built over two years at a cost of £244,000. Traffic first tested it in 1902. Engineered by Lt Col A J Barry, it carried the line over marshland for 416 yards at a height of 67 feet. As a result of the soft ground, each pier had to be built on huge concrete plinths sunk 30 feet into the earth, conventional piles proving unsuitable.

Closure came to the Bexhill West branch on 15th June 1964. Despite local protests, the grand structure that formed its centrepiece – comprising nine million bricks – was blown from the landscape in two phases during May/June 1969 (click here to see the video).

Crumlin Viaduct

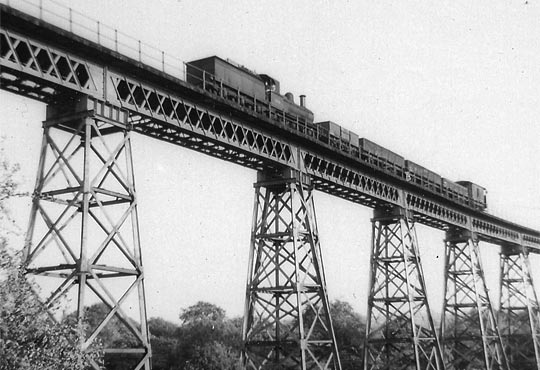

Built to carry the Taff Vale Extension of the Newport Abergavenny & Hereford Railway, Crumlin was the highest railway viaduct in the United Kingdom throughout its operation life and, relative to its size, was amongst the least expensive to build.

Approved by a Parliamentary Act on 3rd August 1846, the structure posed two significant challenges: the need to span two valleys – the Ebbw and the Kendon – and resisting the anticipated high wind speeds. This latter issue prompted Chief Engineer Charles Liddell to decide in favour of cast iron; as well as being expensive and unstable, stone would have compressed the wind flow around rail level, creating a possible hazard for trains passing over.

Two submissions were received in response to the tender invitation, with a design by Scottish engineer Thomas W Kennard being chosen. Contracts were signed in December 1852 and progress was first made in October 1853 when works were built to receive the castings from Kennard’s ironworks in Falkirk. These arrived on site via Newport Docks. The first girder was hoisted into place on 3rd December 1854 and the structure was completed by the end of May 1857, five months ahead of the contractual deadline. It was formed in two sections with a spur of land between the two valleys effectively acting as a ninth pier.

Load tests involving six locomotives took place in the presence of Colonel Wynne from the Board of Trade. Deflection of less than 1½ inches was recorded. Lady Isabella Fitzmaurice officially opened the viaduct on 1st June 1857. Its statistics are impressive: 200 feet high and 550 yards in length across its ten spans.

The last scheduled passenger train ran over the girders on Saturday 13th June 1964. A subsequent survey deemed the viaduct to be in a poor state and the decision was taken to dismantle it. Carried out by Birds of Swansea, work began in June 1966 and took nine months. Even while this work was taking place, scenes were shot on the viaduct for the film Arabesque involving a chase across the maintenance walkway and a helicopter flying beneath it.

Today only the masonry abutments remain.

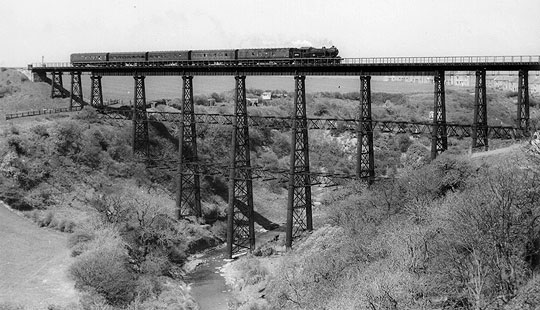

Dowery Dell Viaduct

(taken from Geograph and used under Creative Commons licence)

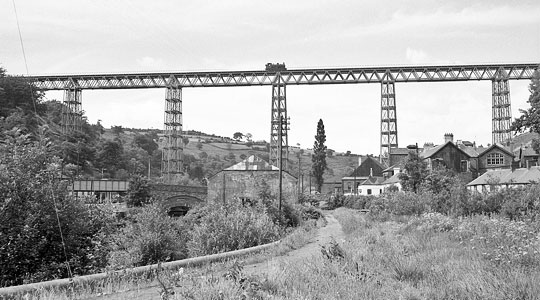

Found near Hunnington, Worcestershire, Dowery Dell Viaduct was a rare – and unusually high – example of a lattice girder structure supported on trestles. It carried the Halesowen Railway for 220 yards as it curved westwards over a steeply-sided valley at a height of about 100 feet. Opened in 1883 and dismantled in 1964, all that remains of the viaduct are its dilapidated abutments and a number of brick bases for the piers.

Eastville Viaduct

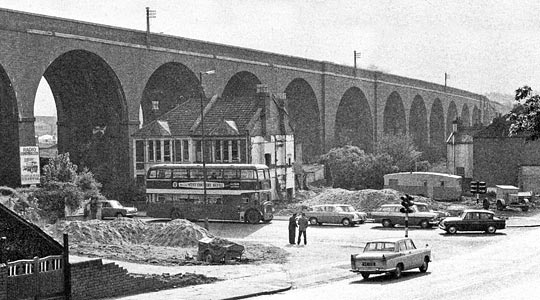

The Clifton Extension Railway linked the Channel Docks at Avonmouth with both the Midland and Great Western networks, the two companies jointly funding its construction. However each had to build their own connecting line, the Midland’s extending for 1½ miles from Kingswood Junction to the east of Bristol. The engineering proved disproportionately challenging, demanding two substantial viaducts.

The seven-span structure at Royate Hill, crossing Rose Green Road, is still standing but the longer one at Eastville – known locally as the Thirteen Arch Viaduct for reasons that need no explanation – succumbed to explosives in 1968 (click here to see the video), making way for the M32 motorway. The viaduct had seen its last traffic three years earlier.

This notable local landmark opened in 1874 and was built entirely in durable engineering brick, curving to the south on a radius of around 44 chains and extending for almost 200 yards.

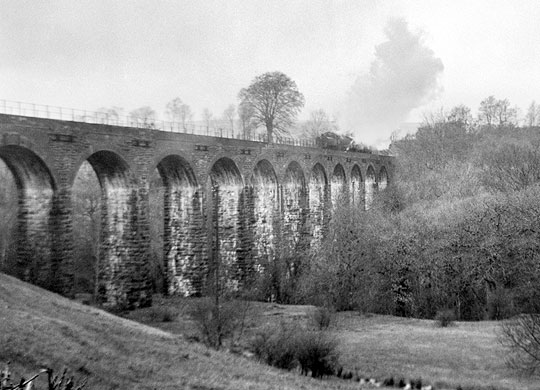

Giltbrook Viaduct

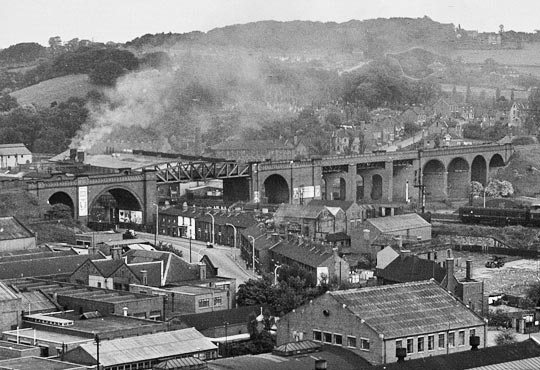

Forming part of the Great Northern’s Derbyshire Extension, Giltbrook Viaduct was erected between May 1873 and November 1875 by contractor Joseph Firbank to a design by Richard Johnson, the GN’s Chief Civil Engineer. Samuel Abbott acted as its resident engineer.

Known locally as Forty Bridges, the S-shaped viaduct reached 60 feet in height and extended for 572 yards across its 43 red brick spans. The structure comprised clusters of 30-foot arches separated by single spans over roads, canals or other railways, with king piers between them.

Counting from the Awsworth end, spans 8 and 23 were converted into dwellings, acting as makeshift air raid shelters.

The viaduct was demolished in 1973 to make way for the A610.

Horns Bridge Viaduct

Consisting of seven brick arches and four girder spans – all flanked by substantial embankments – was a dramatic viaduct at Horns Bridge, just south of Chesterfield. Carrying the Lancashire Derbyshire & East Coast Railway at a height of 63 feet, this was reputedly one of only two places in the world where three railways owned by separate companies crossed at the same place on different levels, the other being at Richmond in Virginia, USA.

Passing beneath the viaduct was the Midland Main Line, off which ran a branch to Brampton. Below these were the rivers Hipper and Rother, the roads to Derby and Mansfield, a couple of footpaths and the Great Central’s Chesterfield Loop line with its associated Hyde’s Sidings.

Having begun in 1897, passenger services over the structure ended on 3rd December 1951, with the line’s complete closure coming in 1957. Although the tracks were lifted, the embankment and viaduct remained intact until 1960 when the girder spans were dismantled. The brick piers and arches disappeared in 1985, making way for road improvements.

Today, the only remnant of the structure is some blue engineering brickwork beside the Midland Main Line.

Kilton Viaduct

In 1865 the North Eastern Railway was authorised to build a line – known as the Saltburn Extension – to serve the ironstone mines around Brotton. This included a spectacular curving viaduct over Kilton Beck, comprising 13 iron girder spans supported by stone piers and reaching a height of 150 feet.

Mining activity caused the viaduct’s foundations to subside in 1911 so the decision was taken to bury the structure in 720,000 tons of shale (mining spoil), forming an embankment instead. During the work, which took two years, one of the piers showed signs of stress – possibly due to uneven tipping – so traffic had to be stopped for a fortnight while the problem was rectified. The work also demanded construction of a long concrete culvert to accommodate the water course.

So the structure is not strictly demolished, but as it’s no longer a visible part of the landscape we deemed it worthy of inclusion.

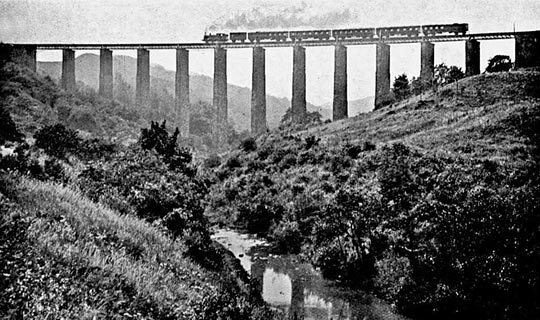

Staithes Viaduct

Built by the North Eastern Railway and its contractor John Waddell, Staithes Viaduct formed part of the fabulous Whitby Redcar & Middlesbrough Union Railway which clung precipitously to the east coast. The project was significantly delayed by financial and construction difficulties.

Designed by John Dixon and comprising 17 spans, the viaduct launched its single track over a deep valley for 263 yards at a height of 152 feet. Its piers were fashioned from wrought iron tubes filled with concrete. Additional bracing was fitted following the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879 although there was no evidence to suggest that the structure would suffer a similar fate. However five years later, a wind gauge was also fitted; this rang a bell in the adjacent signal box when the wind pressure exceeded 28lb/ft2, resulting in traffic being suspended until the viaduct had been inspected.

The line opened on 3rd December 1883 but survived only until 3rd May 1958. Like four other similar structures further down the line, closure brought the viaduct’s dismantlng for scrap.

Tarras Viaduct

The North British Railway’s branch to Langholm opened on 11th April 1864 but became two separate lines a fortnight later following the partial failure of Byreburn Viaduct. Two miles away, Tarras Viaduct had proved equally problematic during its construction, so much so that it delayed the line’s opening. The work was marred by the instant death of a young man in January 1864 who fell to the ground after a plank slipped.

Trains started rolling in earnest over the viaduct in November 1864. Accommodating a single line, it comprised 12 brick arches supported by masonry piers. Eventually steel plates and ties were installed to prevent outward movement of the spandrels.

Beeching’s axe brought an end to Langholm’s passenger service in 1964 although freight continued for another three years. In October 1987, after Tarras Viaduct had been declared unsafe, a firm from Selkirk was brought in to blow it up. So ‘unsound’ was the structure that only half of it fell at the first attempt.

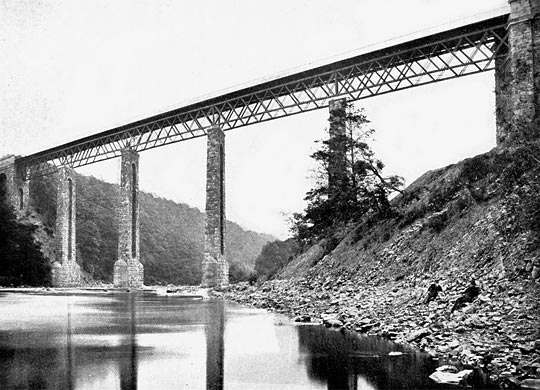

Tees Viaduct

Tees Viaduct, just to the west of Barnard Castle Station, measured 244 yards in length and 132 feet high. Designed by the ill-fated Thomas Bouch for the South Durham & Lancashire Union Railway over Stainmore, it took the strain of its first passenger train on 8th August 1861. Some of those on board were apparently nauseated by its height and movement. Bouch’s original girders (pictured) were later replaced by more substantial steel versions.

Although the main line closed in 1962, the branch to Middleton-in-Teesdale survived for another three years, resulting in the structure remaining operational until April 1965. But on 29th November 1971, demolition men arrived and began the job of salvaging the 120 foot spans. The piers have also gone but the huge stone abutments still cling to their respective hillsides.