Safety and the law

Safety and the law

Railway tunnels and viaducts have been a source of fascination for people ever since the first one became disused – and in some cases, even earlier than that. A generation ago, before the advent of Playstations and the internet, abandoned structures were a regular playground for children who learned much from them about the assessment and management of risk, benefiting them in later life.

But today’s culture is very different. Onerous and often disproportionate health and safety regulations have prompted property owners to take a much more risk-averse approach to security. This is partly driven by a genuine desire to prevent harm but also the threat of action by enforcement bodies or injured parties.

Whatever the background, those members of the public who exercise their right to be interested in railway heritage – and seek to pursue that interest through exploration – can now find themselves coming into conflict with authority.

Page last updated 1st December 2017

Understanding the risks

It is clearly the case that some disused tunnels and viaducts are fenced off despite them being largely benign. This might promote the view that all structures are secured unnecessarily and are safe to enter. That is not the case – they all pose risks although it is probably fair to say that these are rarely greater than the dangers associated with rock climbing, potholing and skiing – and there is not yet a clamour for those activities to be banned.

No exploration can be risk-free. Of the 138 accessible tunnels owned by British Railways Board (Residuary), some are deemed so risky that they are not subject to annual inspections. It is the Board’s position that the public should stay out of its tunnels and off its viaducts. But the fact that people don’t always heed that message is a reality that needs to be managed. So, if your mind is absolutely set on venturing beyond the palisade fencing, what should you do and what do you need to know?

General pointers and advice

- Think twice about it.

- Do you understand what you might encounter and where the risks are?

- Don’t go exploring alone – in case of a mishap, there needs to be someone with you who can go for help.

- Make sure someone knows exactly where you are going and how long you are likely to be. Arrange a time by which you will have phoned to confirm you’re OK.

- Wear robust footwear as well as warm, waterproof clothing.

- Mobile phones don’t work in tunnels.

- For tunnels, take a good torch and spare batteries. Hardhats cost about £10 and are a worthwhile investment in some cases.

- Is the tunnel well ventilated? If not, your health could be endangered by toxic gases.

- Confirm there’s solid ground ahead of you before putting your feet there.

- Keep checking above you for any loose brickwork.

- If you begin to feel uneasy or unwell, head for the exit straight away

Catchpits

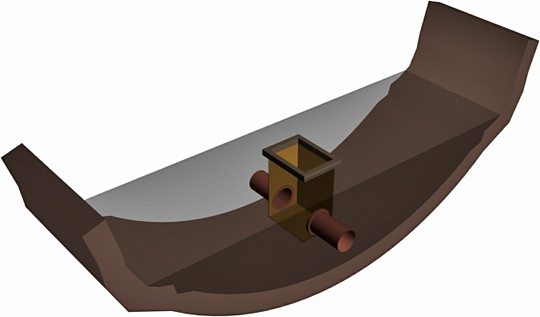

To deal with rainfall or water ingress, viaducts and tunnels have drainage systems. These involve catchpits – holes on the surface in which the water is collected – and a buried pipe to take it away. This system is generally located down the centre of structures built for two tracks, in what would have been the six-foot (the space between the tracks). With single-track tunnels and viaducts, it can be at either or both sides.

A section of exposed and collapsed drain.

With closure, the ongoing maintenance regime comes to an end. This means that drains can become blocked – causing standing water, mud or silt to collect on the surface – or give way altogether, creating holes into which people can stumble. The covers that prevented ballast from falling into catchpits in operational times were often removed by salvage crews, leaving them open. They can be 2-4 feet deep. Hidden catchpits – obscured by mud, debris or vegetation – are a regular hazard associated with most structures.

Structural failure

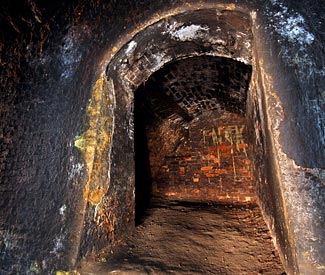

It is almost inconceivable that anyone would be standing directly beneath a brick or piece of masonry at the precise moment when, after more than a century in situ, it decided to part company from its neighbour. That said, water penetration and freeze/thaw action affects most tunnel linings, causing spalling or sections of brickwork to be lost.

It is rare but not unheard of for major failures to occur. Burdale Tunnel in the Yorkshire Wolds is blocked in two places; Perridge and Cheadle tunnels have also suffered collapses, resulting in an exit route becoming unavailable and preventing the through passage of air. Be aware of bulges in the lining – this is indicative of pressure building behind it.

Photo: Mike Elliott

On iron viaducts, the threat posed by corrosion can be locally significant, compromising the strength of handrails and the integrity of the deck plates which can become thin and unable to withstand any weight. Earth and vegetation could mask this potential danger.

Loss of oxygen

Longer tunnels and those with no ventilation shafts or a completely sealed/buried entrance are more likely to contain low levels of oxygen or other gases that pose a risk to health. Generally those risks are greatest in places where atmospheric pressure drops, allowing gases to escape from rock faces or from behind linings. Adits and side chambers are potential hot spots.

Carbon dioxide, carbon monoxide, methane and hydrogen sulphide all present threats. They are often produced by the decomposition of organic matter and are odourless, with the exception of hydrogen sulphide which smells of rotten eggs. Methane is the most destructive of these gases.

If deprived of oxygen, the human body can sustain itself for five minutes without permanent damage. The gases present in air enter the bloodstream within seconds and, if absorbed into body tissues, can disrupt normal physical processes. Increased breathing or heart rates, impaired judgement or coordination, headaches, dizziness and nausea are all symptoms of these gases already having an impact.

British Railways Board (Residuary) carries out risk assessments and puts in place special arrangements to facilitate safe tunnel inspections. These involve the wearing of Personal Protective Equipment, the appointment of attendants at entrances as well as the use of gas detectors and rebreather sets by those who go underground.

Over the past five years, inspection and maintenance staff have been alerted to the presence of health-threatening gases on five occasions. Whilst this might seem a very low number, each one of those events represents a relatively high risk.

Legal matters

Trespass

Trespass is generally a civil rather than criminal matter, except on the operational railway and military land/bases. Landowners may use reasonable force to evict a trespasser. A prosecution for trespass is likely to net the claimant only nominal damages although their legal costs might also have to be met. These can be high.

In Scotland, statutory rights of access to most land and water have been established under the Land Reform Act 2003, on the proviso that these rights are exercised responsibly. This blog offers an overview of the Scottish Outdoor Access Code.

In England, the public can walk freely on some areas of mountain, moor, heath, downland and registered common land without having to stick to paths. This results from the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (CROW). This came into effect on 31st October 2005 and applies to around 865,000 hectares of land.

The walker’s responsibilities under the Act are detailed here whilst maps showing the land currently covered is searchable here.

Criminal acts

A criminal prosecution resulting from trespass would only normally occur in the event of criminal damage – for example, as the result of someone smashing a lock or removing/breaking a section of fencing. The Criminal Damage Act of 1971 sets out two levels for this offence –

- A ‘summary offence’ is limited to damage valued at less than £5,000. The case is heard by a magistrate. The offender can receive a jail term of up to three months and/or a fine of up to £2,500.

- Higher value cases could be heard in either a Magistrates or Crown Court. A magistrate can impose a maximum sentence of six months imprisonment and a fine of up to £5,000. In the Crown Court, the maximum penalty is a ten year prison term.

Over the past five years, damage caused to fencing has allowed children to enter BRB(R)’s tunnels on at least nine occasions, with obvious potential consequences. So beyond their cost and illegality, such acts can expose the vulnerable to real danger.

Who’s liable?

The remarkable relics of our former railway network are a source of understandable fascination. This website exists for that reason and we are not so hypocritical to suggest that you shouldn’t explore them. But it should not be forgotten that people who venture into a fenced-off tunnel or onto a viaduct do so entirely at their own risk and are generally committing a trespass. Having taken reasonable steps to secure their structures, the owner cannot be held liable for any illness or injury that occurs as a result of unauthorised access or criminal damage.