The story of Brackley Viaduct by John Quick:

A modern railway by any standards

The story of Brackley Viaduct by John Quick:

A modern railway by any standards

The pleasant market town of Brackley lies in the south-west corner of Northamptonshire, very close to the counties of Buckingham and Oxford. It is an ancient borough and was of considerable importance in medieval times. Indeed, it was at Brackley where the Barons met King John before the signing of the Magna Carta. Its long, unusually wide main thoroughfare is lined with attractive stone buildings and the area is well-known for hunting, with the Grafton and Bicester kennels nearby.

The railway age arrived at the town on 1st May 1850. The Banbury to Verney Junction line of the Buckinghamshire Railway was a single track cross-country branch with a station serving Brackley at the bottom of the town. Naturally enough, when the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway – later to become the Great Central – opened its station, it was known as the top station. The news of the MSLR’s intention to build a new railway through Brackley and on to London created much debate and excitement. It became evident that the MSLR planned to build a locomotive shed and workshops. The opposition to this was considerable and was lead by the Squire of Turweston, John Locke Stratton. He was also Mayor and a major landowner. The MSL eventually decided to construct their engine depot at Woodford, about 10 miles to the north. With a population of well over 2,000, Brackley would have been a useful source of labour for the company.

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

Royal assent to the MSLR’s bill to build the line – often termed the ‘London extension’ – was received in late March 1893. Tenders were issued for the construction of 92 miles of main line which commenced at Annesley North Junction, about 9 miles north of Nottingham, thence to Quainton Road in Buckinghamshire. At that point, trains were able to use the Metropolitan Railway into London.

The construction of the London extension was split into northern and southern divisions, the dividing point being the viaduct over the Oxford Canal near Rugby, 51 miles 69 chains from Annesley. The engineers for the southern section were Sir Douglas and Mr Francis Fox, and it consisted of contracts 4, 5, 6 and 7. The line in the immediate vicinity of Brackley fell entirely within contract No.5. This was 12 miles 39 chains in length, began just south of Woodford and terminated nearly half-a-mile south of the bridge which crossed the Banbury-Verney Junction line – this was structure No.532.

On 7th September 1894, the engineers recommended that contracts 5 and 6 should be let together. This was because there was little suitable ballast on contract No.6 but more than sufficient on No.5. Topham, Jones & Railton of Westminster put in the lowest tender but that company had already secured contract No.3. As a consequence, J T Firbank was nominated for contracts 5 and 6. However, on 21st September, the MSLR board gave contract No.7 to J T Firbank, then instructed William Pollitt, General Manager of the MSLR, to offer contracts 5 and 6 to Walter Scott & Co of Newcastle. This was accepted at a reduced tender of £470,000. Other contractors who failed to get any work were Kirk, Knight & Son of Sleafard, Monk & Newell of Bootle and S Pearson & Son of Westminster. The first brickwork on number 5 contract was laid in November 1894 when work started on a small 6’ culvert, a few hundred yards north of the passenger station site.

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

Looking at the engineering features on contract 5, we begin at the northern end, a little more than a mile north of the station. Crossing a cutting at Brackley Fields was built a brick arch bridge, No.524. It was 31’0″ high with a square span of 56’6″. It carried a farmer’s track and, in common with the vast majority of similar structures on the line, was built in Staffordshire blue brindle bricks. The line continued in cutting until it passed beneath the road to Towcester. The official plan of the line shows three possible sites for this bridge. The central site was selected and became bridge No.525. It consisted of three arches, the outer two being made wide enough to accept additional tracks which, unfortunately, were never needed. Structure 525 was about 25′ high and over 100′ long. It was demolished some years ago in an attempt to straighten the road which, by this time, was carrying a lot of traffic.

The passenger station was situated immediately south of bridge 525. This station has been described as ‘typical London extension’ but this is not really correct. In truth, it is unique on this line. The MSLR was hoping to use the bridge for public access to the platform but the local authority was unhappy at the proposal as they considered the arrangement would interfere with road traffic! Perhaps the Squire was busy again? The MSLR then had little choice but to build its booking and other offices at the top of the embankment on the Down side. A footbridge connected the public entrance with the platform. The station master’s house stood on the Up side, more or less opposite the booking office.

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

The platform buildings were identical to those at Rugby. In fact, all the buildings on the line between Whetstone and Calvert were executed by a Rugby firm, J Parnell & Son, for about £30,000. The platform was the usual island type but there is evidence that a third platform was considered. Opposite the Down side were the earthworks for this and, on an official plan, the words ‘future platform’ are noted alongside. It has been referred to as the ‘Northampton platform’ but this is generally thought to be a myth. The earthworks were extant when the line closed in 1966. The goods yard contained all the necessary features to deal with a variety of traffic.

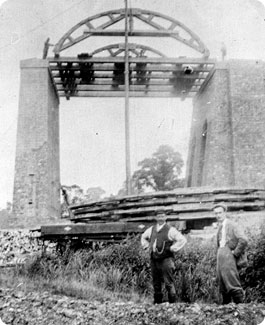

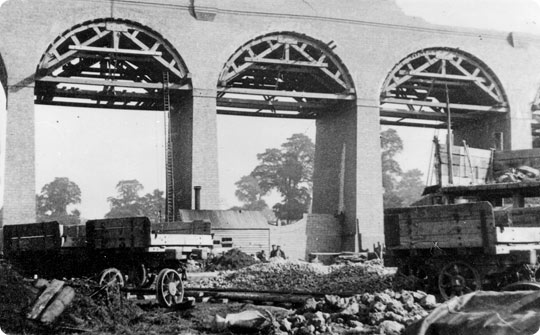

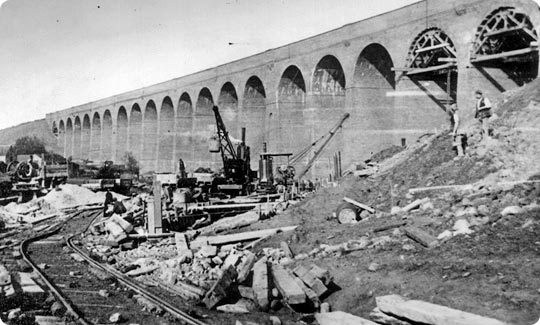

Passing the station, the line continued on its slight curve to the south-east on embankment. A small underbridge, No.526, pierced this, giving the farmer at Burwell Farm access to fields on both sides of the line. It stood nearly 19’ high with a span of 12′. Then came the valley of the River Ouse. Standing more or less at the 147½ mile post was built Brackley Viaduct, one of the major works on the London extension. With the corn mill standing alongside, construction probably began in the winter of 1894/5. It was intended to build 22 arches but this was not the outcome. Locals warned the contractor of unstable ground in the district and, despite the placing of large quantities of wool in the foundations, serious problems were encountered. The viaduct was largely complete when cracks were noticed in the southernmost two arches. Photographs show these and also damage to a nearby store. Urgent remedial action was required and this consisted of the removal of the offending arches and replacement with two steel girder spans, with a massive reinforcement of the next pier. Viaduct No.527 was over 750′ long and a little over 60′ high. It was demolished with great difficulty during the autumn of 1978 – against locals’ wishes – apparently for the hardcore. Immediately south of the corn mill, the contractor had their local head office, with workshops, stables and accommodation for 200 men.

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

The main road to Buckingham was carried over the line, about ¼ mile to the south, by bridge No.528 which stood close by the county boundary. It had one arch only, was 17’ high and had a skew span of 33′. The cuttings on the approach to this bridge have now been filled. South of this point, the railway crossed the main valley of the Ouse on a high embankment which contained over 270,000 cubic yards of rubble. The nature of the clay here was already understood from the days of the construction of the Verney Junction line. Consequently few problems were found in this area. The line of that railway was crossed on an overbridge, No.532, with a skew span of 51′ and a 26′ square span. It consisted of four plate girders, 58′ long. A temporary siding was laid to assist with the considerable traffic in construction materials. Ten chains to the south, contract 5 ended with a small under bridge. This was structure No.533 and crossed a footpath which connected the villages of Evenley and Westbury.

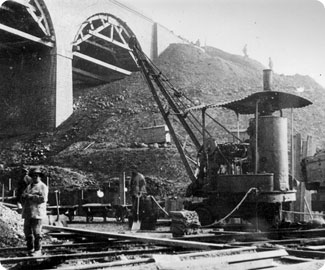

The early days of railway building depended a lot upon men wielding the tools of their trade. These were mainly hand tools – pick, shovel, wheelbarrow. Horses were used as well. But the construction of the London extension was a vastly different affair. Small, four or six wheeled steam locomotives worked over the lightly-laid tracks of the contractor, moving materials and spoil. The steam excavator – or ‘steam navvy’ – was used with great success. They were supplied by Ruston, Proctor & Co of Lincoln and, on an average day, could move about 250 loads, equivalent to about 1,000 cubic yards.

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

They revolutionised the removal of material, saving both time and money. It has been estimated that one excavator was the equal of perhaps 70 men and the cost of removing one cubic yard of material could, depending on the nature of it, fall by anything between 25% and 45%.

When the first main line railways were built, the activities of the makers were recorded by artists such as J C Bourne, but this was not the case with the London extension. The construction of this line was comprehensively photographed by a young, very enthusiastic Leicester photographer, S W A Newton. Newton took very many photographs during the line’s construction, showing the men, their plant and many more subjects. Something in the order of 3,000 photographs and negatives exist and a great many have been published. The Newton Collection is available for study at the Leicestershire Record Office. It is a unique record of the construction of what has been called ‘the last main line’.

The MSLR became the Great Central Railway whilst the line through Brackley was being built, only a change of name was required. On 15th March 1899, the first passenger trains called at Brackley although the line had been in use for coal traffic from July of the previous year. The GCR became part of the LNER in 1923 and, in turn, that company was absorbed into British Railways in 1948. The London Midland Region of BR took responsibility for the line through Brackley in 1958 but, by then, successive governments were desperately trying to cut the heavy losses incurred by the nationalised rail network. The run-down of much of the system began almost immediately. By the time the London extension was closed as a through railway – which occurred on 3rd September 1966 – the line was only a shadow of what it once was. The demolition contracts were implemented, in some areas, with immediate effect.

Photo: GCRS/John Quick collection

The London extension was engineered to an extremely high standard and to a generous loading gauge, often referred to as the ‘Berne’ gauge. Apart from a very short section north of Nottingham at a gradient of 1 in 100 and a longer part of 1 in 132, the gradients were easy at 1 in 176. With just one exception, curved sections of track were set at a minimum of 1 mile radius.

Many do not realise the complete absence of road level crossings on the line. Even the farmers’ cart tracks was carried over or under by a bridge. Indeed, the first level crossing out of the GCR London terminus at Marylebone is at Beighton, about 6 miles south of Sheffield. It will be seen then that the London extension that passed through Brackley – which was built and opened in the last decade of the 19th century – was virtually built to 21st century standards! What a most useful route it would have been had it not been deliberately destroyed.

One or two schemes have been proposed to reopen the line, mainly for heavy freight in connection with the Channel Tunnel. After all, it was all part of Sir Edward Watkin’s grand plan to run MSLR trains into the Gare du Nord in Paris. The idea of a tunnel under the English Channel is not new.

A preserved part of the line at Loughborough runs passenger trains on a regular basis. It is possible however that a much longer piece of it at the southern end, including the part through Brackley, may reopen as a new high-speed railway to Birmingham and the Midlands.

More Information

| Leicestershire County Council | Historical views of the completed viaduct |