The story of Belah Viaduct: Don't Look Down

The story of Belah Viaduct: Don’t Look Down

“Good grief!” exclaims Nigel Carmichael as his jaw hits the floor. From the lofty vantage point of a Cumbrian hillside, the retired Signal and Telegraph man peers down on two stone abutments which sit forlornly either side of the valley like a pair of forbidden lovers. When he was last here almost 50 years ago, the air gap between them was occupied by the iron leviathan that was Belah viaduct. But no longer. “It’s just empty, gone, nothing!”

Belah was the centrepiece of an ambitious trans-Pennine connection between Barnard Castle and Tebay, involving a tortuous climb up to Stainmore summit, 1,370 feet above the sea. The line was a creation of Thomas Bouch, a talented engineer whose many grand achievements would later be overshadowed by Britain’s most notorious railway disaster.

Bouch was a Cumbrian son, born in Thursby in February 1822 and educated at the local school. He was no great scholar and, aged 16, headed to Liverpool where he accepted an apprenticeship with a firm of engineers. He didn’t settle, soon returning home as assistant to railway surveyor George Larmer – the first rung on a notable career ladder.

It was the age of the train and mania for them was at its maddest. Opportunities abound. Bouch spent four years with the Stockton & Darlington Railway before securing the unlikely post of engineer and manager for the Edinburgh & Northern. He was a month short of his 27th birthday. His pioneering spirit lead him to introduce the world’s first roll-on roll-off train ferries across the Tay and Forth, earning him an enviable reputation amongst his peers.

By the time of his departure from the E&N in 1851, Bouch was already installed as an associate member of the Institute of Civil Engineers. In a consultant capacity, he surveyed and planned a network of routes across Scotland and northern England, amongst them the South Durham and Lancashire Union line through the wilderness of Stainmore.

With the support of industrialists from either side of the Pennines, the SD&LU was conceived as a two-way goods link, moving coal and coke to the blast furnaces of Barrow and iron ore back to Teesside. The sparsity of the population relegated passenger traffic to the role of second fiddle.

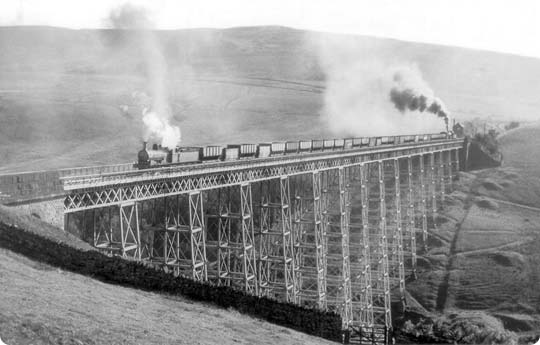

Without a murmur of discontent, Parliamentary ascent was granted in July 1857. Nine construction contracts were let, including separate agreements for three iron viaducts. The first, built on stone pillars, carried the line over the Tees at Barnard Castle whilst Deepdale, an iron trestle structure near Lartington, offered views over “a charmingly romantic glen” – rose-tinted terminology from an 1890 journal. But these two were dwarfed by a triumphant 1,040 feet span across a ravine south of Barras, through which flowed the River Belah.

© Mark Keefe

www.kirkbystepheneast.co.uk

Construction of the wrought and cast iron viaduct got underway in November 1857 when Henry Pease, the new Member of Parliament for South Durham, laid the foundation stone. Costing £31,630, contractors Gilkes, Wilson & Co erected Belah in a little over two years. At 196 feet, it was the tallest bridge in England.

Freight wagons first pressed the sleepers of the 46-mile single line on 4th July 1861, with the passenger service inaugurated one month later. Two trains per day ran in each direction, operated by the Stockton & Darlington. Bouch’s brother William was the line’s Locomotive Superintendent. It was a period of managerial upheaval. Within a year, the line had been absorbed by the S&D which, in turn, was taken over by the North Eastern Railway in 1863.

Traffic levels exceeded all expectations, so much so that the route struggled to cope with the insatiable hunger of Furness’ burgeoning iron and steel industry. As new works sprung up around Workington, the burden grew heavier. The NER board responded in 1870 when authority was granted for the line to be doubled. Within a decade, the annual haul of coke heading west over Stainmore reached one million tonnes.

Those loaded trains felt the strain as they laboured optimistically to the summit. The 13-mile climb from Barnard Castle was rarely flatter than 1 in 67 whilst the ten-mile descent towards Kirkby Stephen was even steeper, with one section falling by 1 in 59.

The line’s success mirrored the fortunes of its engineer. In 1854, Thomas Bouch had submitted a proposal to bridge the Firths of Tay and Forth to directors of the North British Railway. It was dismissed as “the most insane idea ever to be propounded” but, by 1870, the case was overwhelming and work finally got underway on a crossing of the Tay in January 1873. Bouch was at the helm.

It was Britain’s largest single engineering project and, at over two miles, comfortably the longest construction anywhere in the world.

The undertaking was beset by problems. Surveys had indicated a foundation of bedrock but gravel was found instead. Bouch hastily redesigned the structure to lighten the load. Six men died in an underwater chamber. One of the main girders succumbed to the weather and fell into the river. And yet, despite these setbacks, the bridge was completed just a few weeks behind schedule and passed a painstaking inspection by the Board of Trade.

In June 1879, a year after it opened, Queen Victoria crossed the water on Bouch’s bridge and duly rewarded his endeavours with a knighthood. The events of the following winter were tragic and well charted. On Sunday 28th December, both the bridge and a train plunged into the Tay during a violent storm, claiming 75 lives. The subsequent inquiry placed the lion’s share of blame at Bouch’s door, bringing his career to a screeching halt. He died four months after the verdict had been delivered.

Belah though was still standing and did so for 102 years.

As the 20th Century opened its doors, the NER was running five trains either way across Stainmore, connecting Barnard Castle with Tebay in three-quarters of an hour. Specials ran at holiday time through to Morecambe and Blackpool. Durham miners enjoyed the view down the Eden valley en route to their union’s convalescent home in Ulverston.

Like many others, this community service was forced to surrender to the howling blizzards of 1947. In early February, a Darlington-bound night train foundered near the summit. Passengers were transferred to the trailing carriage which was uncoupled and hauled back to Kirkby Stephen. For eight weeks, clearance teams fought the biting weather, assisted by Army flame throwers and a pair of rail-mounted jet engines. Victory was eventually secured by shovel power and elbow grease.

For seven years during the fifties, the unenviable task of keeping Stainmore’s linewires well connected sat on the shoulders of Nigel Carmichael and his mate Albert. Based at Barnard Castle, this pair of adventurers toured the railway by train or Wickham trolley, looking after the signal and telegraph equipment. This often involved working at heights, for which Albert was not well suited as he had a fear of them. Their patch extended up a branch line to Middleton-in-Teesdale and across the Pennines to Merrygill signalbox.

Life in the open air had much to commend it, though its appeal withered during those harsh winters. “It became a completely different world” shivers Nigel. “There used to be a lot of faults – telegraph wires coming down. And that was my job – to climb the pole. My mate used to pull the wires up and I had to join them. Your fingers were frozen! However, you got over it and it got warmer the longer you were up there. Except the toes – they were always cold!”

Belah was a regular haunt. They’d travel up to Barras and walk the last mile, crossing the viaduct to the signalbox by the western abutment. A handful of telegraph wires ran the length of the structure, supported on three-foot long arms extending out from the northern side. A copper binder attached the wires to insulating pots but sometimes, in strong winds, the binder would break and the wire swing out over the drop.

“If the furthest one went, we’d get a stick to try and hook it back. Sometimes I used to go out onto the arm. You never looked down! They provided safety belts but we didn’t use them. You never thought about falling – all you were interested in was getting those wires through and the job completed.” When a train came, the girders would rumble and shake a little, “especially if you were out on those arms and couldn’t get back. The signalman would shout ‘what the hell are you doing there!’”

Nigel delighted in Stainmore’s wildlife, particularly during springtime when the birdsong was at its sweetest. He played delivery boy for one of the signalmen who had a profitable sideline catching rabbits to feed his friends in Barnard Castle. Peewit eggs were also a favoured delicacy. One day he looked down from the girders to see the Belah hounds in pursuit of a fox, closely followed – on foot – by the huntsmen and a handful of platelayers. And a chap called Moscoff once tried fishing from the viaduct. “He had this long line weighted by a great big stone so the wind wouldn’t blow it too much. He didn’t catch anything!”

Despite its isolation, Nigel and Albert were rarely alone. A permanent way gang of a dozen men fettled the track down from the summit. They were often around. And three girls from a remote farm used the track as a walking route to Barras station, where they caught the bus to school.

© Mark Keefe

www.kirkbystepheneast.co.uk

Belah box was a bleak outpost, employing three men and open around the clock. The fire was always burning. Passing trains dropped off lumps of coal together with cans of water to supplement supplies from a nearby well.

Nigel would sit in the window, watching the world go by and putting it to rights. Occasionally the signalman would announce “I’m going out for ten minutes – do you mind looking after the job?”, so Nigel was left pulling the levers. He’d return a couple of hours later saying “sorry, I was delayed!”

Evening entertainment was laid on by an old tramp who’d set up home in an abandoned cottage and appeared regularly in the box. “Fantastic fella” declares Nigel. “He’d been in the Army and the Palestine police, and he’d tell these stories of his time on the road, living in haystacks! I could have listened to him for hours. He had a great knowledge – very well educated – and liked his way of life.”

The livelihood of our S&T duo came under threat as the decline of Britain’s railways gathered pace in the late fifties. “I heard rumours that the line was going to close so I thought I’d better get another job at Darlington.”

Proposals to withdraw Stainmore’s passenger services spoiled the Christmas party of 1959. Local forces were marshalled and a petition marked the start of a vociferous campaign, aimed at securing a reprieve. Ultimately the quest was futile. The remaining coke traffic was soon diverted via Carlisle although the line’s new diesel units continued to carry travellers for another couple of years.

© Four by Three

The closure programme finally claimed Stainmore on the 20th January 1962. Four hundred enthusiasts jemmied themselves onboard a double-headed steam special, bedecked with a wreath and accompanied on bagpipes by the melancholy sounds of Auld Lang Syne.

It was the end of the line for Belah. Piece-by-piece, in an act of extraordinary vandalism, its ironworks were dismantled and salvaged for scrap. A year after the axe fell, one of the railway’s greatest engineering masterpieces had been cut from the landscape.

Part of the route still clings to life through the exploits of volunteers from the Eden Valley Railway, who operate tourist trains between Appleby and Warcop. Their official aim – though clearly a pipe-dream – is to relay track across the moors and reconnect Barnard Castle with the railway network. This mind-boggling aspiration would involve a £25million investment at Belah.

For those who can’t wait for pigs to fly, three survivors of Belah’s past await the attention of folk on Shanks’ pony. Two colossal abutments – notable feats in themselves – still mark the extent of the former span whilst the tattered remains of the signalbox, abandoned by the maintenance men, have withstood the ravages of forty Stainmore winters. Footpaths pass beneath these relics, within 400 yards of public, if rather minor, roads.

As Nigel muses, “I thought this railway would last forever but, with modernisation, it’s all gone.” And the Belah valley is palpably poorer for it.

More Information

| Cumbrian Railways | Brief history and photos of Belah viaduct |

| Cumbrian Railways | Timeline of the Eden Valley and Stainmore Railway |

| Eden Valley Railway | The Eden Valley Railway, past and present |

| Stainmore Railway Company | Kirkby Stephen East station, past and present |