The tunnels and viaducts of the Whitby-Loftus line: Against all odds

- Author: Michael Aufrere Williams

- Source: Journal of the Railway & Canal Historical Society (No.218)

- Published: November 2013

The tunnels and viaducts of the Whitby-Loftus line: Against all odds

As finally built there were three tunnels on the sixteen mile line between Whitby and Loftus. These were the Sandsend (or Deepgrove), the Kettleness, and the Grinkle (originally Easington) tunnels. The longest was Sandsend tunnel (1,652 yards [1511 m]). The tunnel is, for the most part, straight; however, there is a curve to the north for the last 350 yards –

Kettleness tunnel was 308 yards [282 m] long –

Grinkle (originally called Easington) tunnel was 993 yards long [908 m] –

However, the only tunnel authorised in the original 1866 Act was the Easington, which was then to be 1,324 yards long, where work on the line began with the cutting of the first sod on 25th May 1871. Progress was satisfactory along some sections of the line, but the Engineer’s Report presented to the Directors of the company at their meeting of 9th May 1872 stated baldly that on the Easington tunnel to Loftus section, “Nothing has been done. Machinery there, then found the tunnel could be halved by a slight deviation. Careful examination of the ground satisfies us that we shall not meet with any extraordinary difficulty in the execution of the tunnel.” The Engineer, Mr J H Tolmé, was often given to exaggeration and prone to telling the directors what he thought they wanted to hear. His forecast concerning the future construction of the Grinkle (Easington) tunnel will, as will be shown, incorrect. The tunnel was shortened, though, for Tolmé’s report of 9th September 1872 mentions that, after arrangements with the landowners, the tunnel has been shortened from nearly a mile in length to considerable under half a mile (792 yards). This deviation, along with other changes to the 1866 plans led the directors, at a meeting on 12th October 1872 to note that “it is desirable that parliamentary sanction should be obtained to the deviations which have been necessary in carrying out the works upon the railway”. At the directors’ meeting of 11th February 1873 they “resolved that the Bill now submitted for authorising the diversion and alteration of the line and levels of the WR&MUR and for other purposes be and the same is hereby approved”. It is interesting to note that work had already been undertaken on these alterations, the main ones being bringing the line closer to the sea between Whitby (West Cliff) and Sandsend and the tunnelling changes at Grinkle and along the cliff face between Sandsend and Kettleness. Thus the 1873 Deviation Act was passed. The plans issued with the 1873 Act clearly show the new length of tunnel at Grinkle and six new ones proposed between Sandsend and Kettleness. However, there is no mention of any moneys spent on tunnelling until the twenty-first Engineer’s certificate presented to the 4th April 1873 meeting of the directors where it was noted that £1,000 had been spent on tunneling. This must have been on the Sandsend-Kettleness section where, Tolmé reported to the directors on 1st September 1873 “the headings for the short tunnels through the jutting points of the cliff are nearly all driven”. Unfortunately, in the same report, Tolmé had some bad news concerning the Grinkle tunnel: “A slip which took place in the embankment at the southern end of the Easington tunnel has caused a great deal of trouble and delay… A bed of quicksand was also met with in the tunnel heading, which considerably retarded the work…”

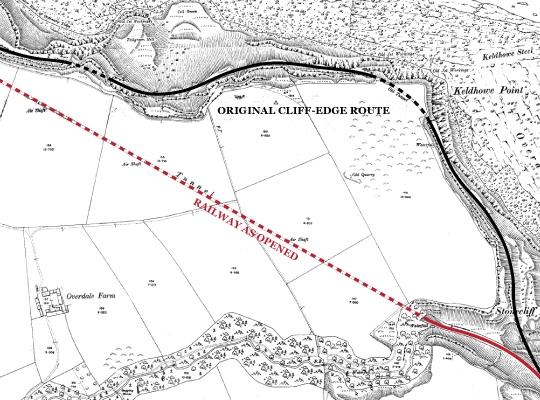

Without any doubt at all, the decision to initially construct the line around the cliffs between Sandsend and Kettleness was not only a major mistake, but the cause of the line’s failure. Nevertheless a considerable amount of work was done on the various tunnels as is indicated by Mr Tolmé’s last engineer’s certificate. In that certificate of 20th October 1873 he reports that, so far, £4,681 had been spent on the various tunnels. The problems caused by the cliff edge works as well as those at Grinkle tunnel brought the company to the edge of bankruptcy, and resulted in the sacking of the contractor, John Dickson at the end of 1873 and of the Engineer a few months later. It is impossible now to know how much work was actually done (no earthworks of any kind remain on the cliff edge section). However, a more recent historical Ordnance Survey map (before 1923) shows a tunnel at Keldhowe Point on the abandoned section of the line. There is no evidence for the existence of this tunnel other than the map. However, even the major tunnelling works which eventually took place further inland did not lessen the cost.

By the summer of 1874 the company was in considerable financial difficulty. Creditors were threatening to take legal proceedings against the company; horses and locomotives belonging to the company were sold at auction; complaints from members of the public regarding damage caused by the company and letters from disgruntled shareholders were arriving regularly; attempts to attract further investment failed dismally and, by 12th November 1874, the company’s bank account stood at £963.15.6 [£44,054] (and this only after the better of the two locomotives had sold for £750). The contractor had been sacked, and work on the line had ground to a complete halt. There was only one option open to the directors if the line was to be completed: an agreement with the North Eastern Railway company. On the 12th November 1874 the directors met to a consider a letter they had received from Mr C N Wilkinson, the Secretary of the NER, dated 23rd October 1874 in reply to the WR&MUR’s directors’ wish to open negotiations with the NER for taking over the construction of the line. At this moment the NER’s reply was cautious:

Central to the demands of the NER was that the cliff edge line be abandoned; clearly it was not, in their opinion “properly laid out”. At last in May 1875 an agreement was made, ratified by the Whitby, Redcar and Middlesbrough Union Railway Act of 19th July 1875, between the North Eastern Company and the Directors of the Whitby, Redcar and Middlesbrough Union Railway to complete the line “with all despatch”, and “in a substantial and satisfactory manner”. The NER would find the necessary capital and work the line upon completion.

Initially, the idea was for a major deviation away from the coast to be made. This would certainly have been a cheaper and easier option, but the new line was never begun. Interestingly, it would have included a tunnel near Mickleby of 525 yards in length at an estimated cost of £13,650. The cliff edge section between Stonecliff End and Holmsgrove was indeed abandoned, but the deviation line inland was never built; instead, a tunnel of length 1,652 yards was built which by-passed the cliff edge line and ran from Deepgrove to Holmsgrove where it emerged for a short section in the open air before entering another – Kettleness – tunnel. It is likely that the North Eastern Railway (with, no doubt, the agreement of the WR&MUR) considered that too much had already been invested in the line to make such a major deviation, or, more likely, that the additional new cost would not be recouped by savings in working or maintenance.

The Directors’ Report to their shareholders of 22nd February 1876 clarified the position: “As provided by the terms of the Agreement, the North Eastern Company has applied in the present session for powers to make a Deviation of the authorised line, and the Bill is about to be submitted for your approval. The deviation is less extensive than was proposed last Session, and substitutes for the line along the cliff about a mile and a quarter of railway almost all in tunnel.” On the 13th July 1876 powers for the deviation of the line through what was then known as Deepgrove tunnel (and for the abandonment of the partly constructed works along the cliff top) received the Royal Assent. The North Eastern Railway had immediately recognised the main problem, but its expensive solution (the construction of Deepgrove tunnel) was to become an important contributory factor for the line’s financial difficulties throughout its life and, indeed was, as will be seen, to be the immediate cause of its closure.

However, between 1875 and 1879 no work on this new tunnel was undertaken. The reason for this is clearly explained by the memorandum of the NER Chief Engineer, Mr T E Harrison. Mr Harrison was writing just after the long-delayed opening of the line in December 1883 and felt the need to explain and justify the length of time it had taken to construct such a relatively short line. According to this memorandum almost every element in the construction of the line when taken over by the NER in 1875 was faulty. This document has been discussed elsewhere and it is a most important source for understanding the early history of the line. Concerning the tunnels Harrison wrote, “…the surveys were so inaccurate that had the original tunnels been completed [those around the cliffs and at Easington], they were so out of line with each other, that no junction could have been made with them at all.” The Harrison memorandum gives the clearest explanation as to why the construction of the Deepgrove tunnel began so late in the proceedings. It was necessary to get all the other deficiencies remedied first. At Grinkle tunnel problems continued; the Harrison memorandum indicating that the delay in opening the line was caused in part by two major landslips at the south end of the tunnel and another a little further south “extending over four acres of land which slid away for 300 yards.”

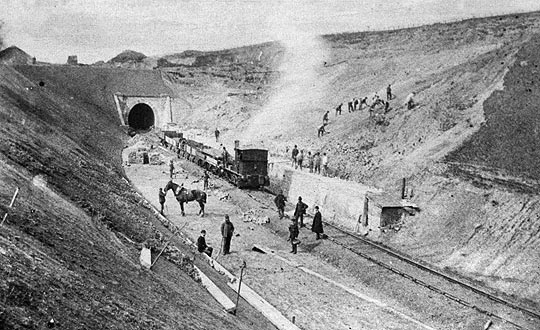

Photo: Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society

Reports submitted to the half-yearly meetings of shareholders between October 1879 and October 1882 indicate that this was the period of the construction of the tunnels between Sandsend and Kettleness. On Friday 24th October 1879 the shareholders of the company were informed that “The Mulgrave [Deepgrove] tunnel is commenced, also involving in its construction a large amount of very tedious work; but the Directors have reason to believe that the Contractor is proceeding surely and steadily (about 800 men being daily employed…” Six months later the shareholders were informed that, “Much time, however, must yet elapse before the line can be opened throughout, owing to the very heavy amount of tunnelling to be accomplished…” Another optimistic report in October 1880 indicated that, “The Directors are informed that rapid progress is now being made…where the tunnel through the ironstone beds, near the Alum Works, is being vigorously pushed forward…” However, it was at the next shareholders’ meeting that the problem of landslips on the line became serious. At this meeting (17th March 1881) a letter from Harrison was presented in which he gave details. “The material at the Easington tunnel had for some distance turned out to be wet sand instead of shale as was expected, and this requires the tunnel to be invested with stronger brickwork and all to be timbered in the tunnelling, which as near as I can estimate will cost about £10,000 more than the contract.”

The line around the cliffs at Kettleness proved equally problematic. Harrison recalled in his 1883 memorandum that, “The three great slips that have taken place on this line are such I have never before in my long practice experienced… The slip in the face north of the Kettleness Tunnel has rendered it necessary to make a considerable deviation of the line for a length of 726 yards, including a tunnel 308 yards in length… The Kettleness (sic) [he means Deepgrove] tunnel is 1,621 yards long; a heading is made throughout its whole length, and there are only 540 yards remaining to be completed, 1,081 yards being finished…”

Photo: Whitby Literary and Philosophical Society

This work proved costly: Kettleness tunnel cost in the region of £5,000 to construct. The tunnelling work was still in progress as late as February 1882. A complaint by the master of a ship that had run aground near Whitby because lights on the cliffs near Sandsend had been mistaken for the Whitby lighthouse was investigated by Trinity House. Coastguards at Staithes and Whitby stated that these “lights” were in fact open fires at the entrances to the long tunnel at Deepgrove and Holmsgrove, provided for illumination for the shift workers involved in the tunnelling. This had been going on for two or three years. After the complaint was dealt with these lights were discontinued. It seems that the tunnels had been completed (or nearly completed) by the October of 1882, for the Shareholders’ report for that month stated that, “…general engineering works…nearly completed…extra works…required on the viaducts…”

The North Eastern Railway spent a considerable amount of money on the construction of the three tunnels on the line. The final cost for the line amounted to £655,077 of which the NER contributed well over £350,000. This high cost was due almost entirely to the need to improve the viaducts, to build or complete the tunnels and to make all the improvements so clearly delineated in the Harrison memorandum. Nevertheless the final product reflected the money spent upon it. Visual evidence, showing the interior of the Sandsend (Deepgrove) tunnel over 120 years after its construction and 50 years after its abandonment shows a very solid and well-built structure. Indeed, so well-built were the tunnels that there is very little reference to them in the three formal inspections carried out by the Board of Trade in 1883, thus indicating that they were not a cause of any concern for the inspectors.

There were two slightly unusual elements in the construction of Sandsend tunnel. Two adits or spoil tunnels were constructed so that some of the excavated material could be taken right to the cliff edge and easily dumped onto the rocks below.

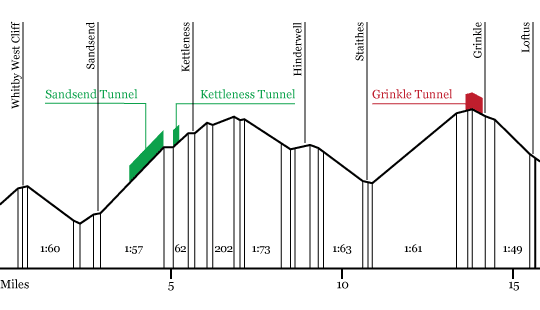

The line was difficult to work. The gradient map shows the many steep rises and falls between Whitby and Loftus.

Especially difficult for train crews was the 1 in 57 bank from Sandsend to Kettleness (with a short stretch of 1 in 62). Most of this steep climb was through Sandsend tunnel; it is not known whether any ventilation shafts were built at the time of the construction of the tunnel, but there is evidence to show that by 1895 there were two in existence. These were not enough and it was decided to ease the difficulties for the drivers and firemen labouring up this difficult stretch of line. Although there is no direct evidence, complaints from the train crews must have been regular enough and loud enough to make the NER construct three new shafts. Detailed plans of these exist in the National Archives. They were built in 1900.

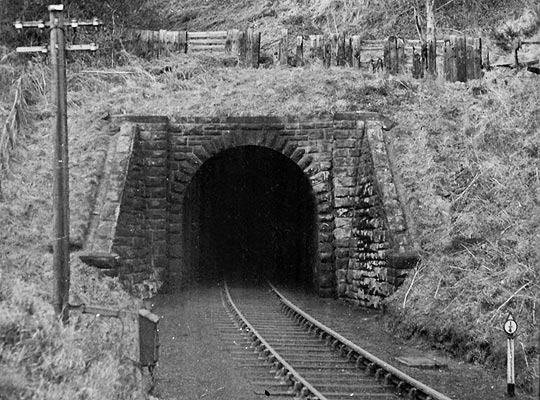

As far as the primary sources are concerned, the tunnels pass out of history until September 1957, when the announcement was made that British Railways were to close the line. The ostensible reason was the cost of immediate and future maintenance, it being considered that £57,000 needed to be spent, mainly on the tunnels and viaducts, in the next five years. This, plus the limited income from the very few passengers that the line carried, was a difficult argument to counter. A glance at the north portal of Sandsend tunnel shows the distortion of the brickwork and the out of alignment tunnel mouth. This photograph was taken c.1956. British Railways were sufficiently alarmed by the inherent danger of the situation that they put in place temporary repairs, reinforcing the misshapen brickwork with steel rails.

However, while maintenance problems were absolutely necessary, it is more likely that the demands of the 1955 Modernisation Plan had more to do with the closure of the line than the (admittedly large) expense of maintaining the tunnels and viaducts.

When the line closed to all traffic on 5th May 1958 (the last trains running on 3rd May) the tunnels were left to the vicissitudes of time and weather. However, as has been noted, so well-built were they that well over 50 years later the interiors of Kettleness and Sandsend tunnels are still in good condition, except for the collapse at the north portal of Sandsend. Access to the south portal of Sandsend tunnel is straightforward, as is the north portal of Kettleness tunnel, but the respective north and south portals of these tunnels can only be reached by passing through the tunnels, as the track bed on the cliff face at Holmsgrove is totally inaccessible. While the ventilator shafts of Sandsend tunnel exist, the exits in the fields above have been capped, and there is now no sign of them.

More Information

| Kettleness Tunnel | Forgotten Relics website |

| Sandsend Tunnel | Forgotten Relics website |

Sources

- HL/PO/PB/1/1873/36 & 37 V1 n 162 [Local Act, 36&37 Victoria I, c. cxxi (1873)]

- HL/PO/PB/3/plan1873/W13

- Tomlinson, W W,

- The North Eastern Railway; its rise and development

- (London, 1914)

- The National Archives: RAIL 527, RAIL 743, RAIL 1110, MT 29

- Michael Aufrere Williams,

- The Whitby – Loftus Line

- (Staithes, 2012)