Whitrope Tunnel

Whitrope Tunnel

The Border Union line, built by the North British Railway and known as the Waverley, plotted a course through the often-remote landscape of the Scottish Borders from Carlisle to Hawick where it joined the company’s existing network. Here the first sod was turned on 7th September 1859, the line having been authorised by a Parliamentary Act earlier that year.

The Whitrope Contract, awarded to William Ritson, extended for 4 miles 5 furlongs and within it were two of the line’s most challenging structures: the 14-arch Shankend Viaduct and Whitrope Tunnel, Scotland’s fifth longest at 1,208 yards. Its construction, beneath Sandy Edge, was a remarkable triumph. It climbs a rising 1:96 gradient to the south and features curves at both ends, describing an S-shaped alignment. Rail level is 311 feet below the highest point of the hill, the strata being predominantly red sandstone, with limestone at the southern end. Whitrope Summit, 1,006 feet above sea level, lies 300 yards further Up the line towards Carlisle.

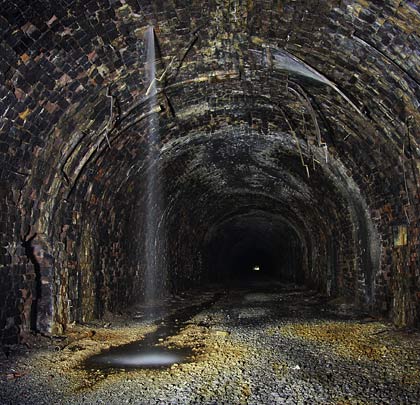

Headings were driven from five construction shafts. 400 gallons of water gushed into the workings every minute; of this, about 216 gallons entered by No.2 shaft alone. To minimise its impact on the work, this influx was managed by a complex drainage system.

At its peak, 600 navvies worked on the tunnel, experiencing huge variations in temperature which caused them to work in coats one minute and topless the next. At least two of them lost their lives. On 22nd April 1859, a ganger named Kingdom chose to descend one of the shafts by rope instead of the ladder provided. About 90 feet from the bottom, he lost his grip and fell, sustaining hideous injuries.

In March 1862, a group of Irish navvies celebrated St Patrick’s Day by stealing all the food and drink from a pub in Longburnshiels, wrecking the place and then attacking a number of Scottish and English labourers who lodged there. The rioting continued for days after.

The tunnel was inspected for the Board of Trade by Captain Tyler on 21st June 1862. Six weeks later, with freight services already running, the route’s formal opening for passenger traffic was marked by a huge banquet in Hawick, attended by upwards of 700 dignitaries.

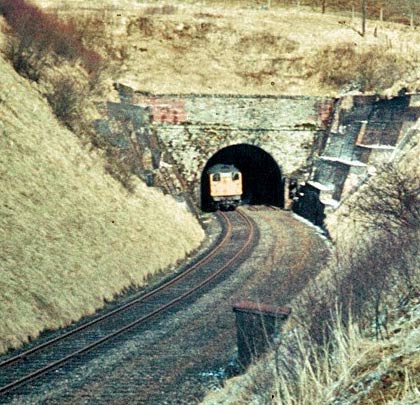

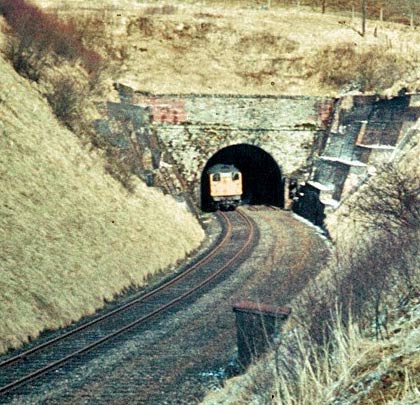

At its southern end, the tunnel features a modest masonry portal with ashlar voussoirs, projecting band course and plain spandrels, with a tall parapet set into hillside. On the approach cutting’s east side, a vast retaining wall of engineering brick – built as a result of the soft, unstable rock – comprises irregular terraces to hold back the hillside. Inset bricks are laid to form a sloped wall, all benefiting from a rock-faced ashlar supporting wall to ground level with plain copings. To the west is a lesser structure of similar style. The north portal enjoys the same design but the retaining walls are less extensive.

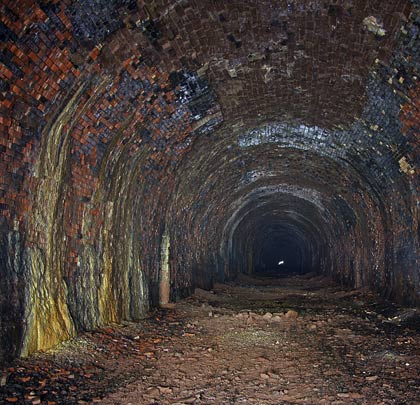

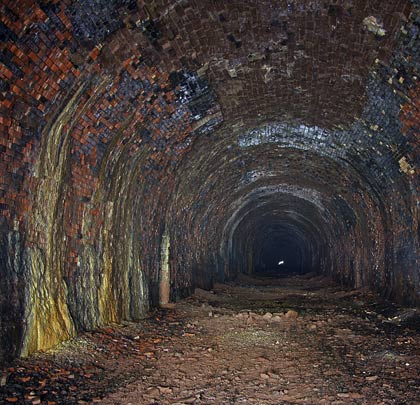

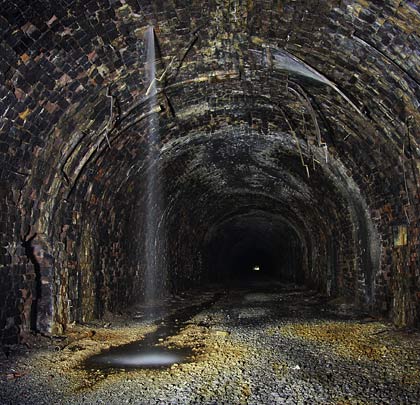

Although the tunnel was originally lined with masonry, substantial sections were replaced in brick over time. However much of this remedial work has itself deteriorated to the point where a large proportion of the bricks have lost their outer face, except where engineering brindles were used. Generally, the lining is in a poor condition, a consequence of the considerable water ingress. Despite all the shafts being hidden behind the lining, at least three of them discharge vast quantities of water into the tunnel through weep holes. The downpipes that used to carry this deluge to the drain have been removed, together with a number of catchment trays. Large areas of calcite are apparent on both walls but there is surprisingly little pondling.

The tunnel still boasts its ballast base, with one open catchpit providing access to the large central drain below the trackbed. Inserted into both sidewalls, which locally are supported on exposed rock footings, are generous refuges of assorted proportions.

At the south end, distortion of the lining prompted the insertion of 16 steel ribs with infill brickwork; several of the ribs have strengthening webs at the crown. However in March 2002, a section of roof immediately to the south of this section gave way, depositing many tonnes of rock and debris onto the solum. Since then the previously-open tunnel has been secured with steel fencing.

The Waverley line closed in January 1969 after which the Up line was soon lifted. The Down line was visited by an engineer’s special on 1st April 1970 before it too was taken up. In recent years, the efforts of the Waverley Route Heritage Association – which has laid a section of track on the approach to the tunnel – have been rewarded with the Grade B listing of the tunnel, affording it some future protection.