Tyler Hill Tunnel

Tyler Hill Tunnel

The world’s first tunnel on a passenger line formed a key part of the Canterbury & Whitstable Railway, known affectionately as the Crab & Winkle. Engineered by George Stephenson with John Dixon as his deputy, the six-mile route connected Whitstable’s specially-constructed harbour with the centre of Canterbury. Both people and goods were accommodated from the outset.

Royal Assent was granted on 10th June 1825; by the following autumn, 400 yards of tunnel had been excavated. Connection between the two ends was made in May 1827, but on 15th June a considerable section of roof fell in, injuring one man who was taken on a cart to the Kent & Canterbury Hospital, “covered in blood”.

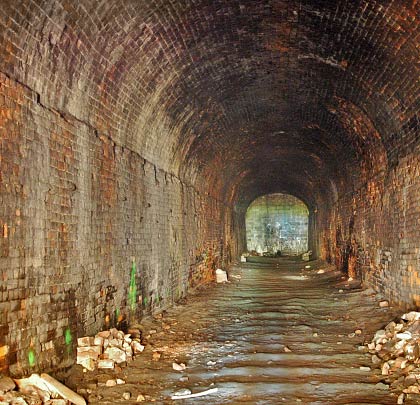

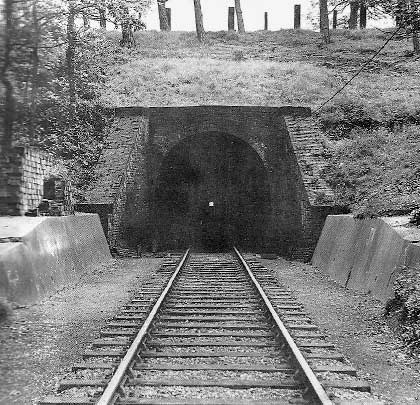

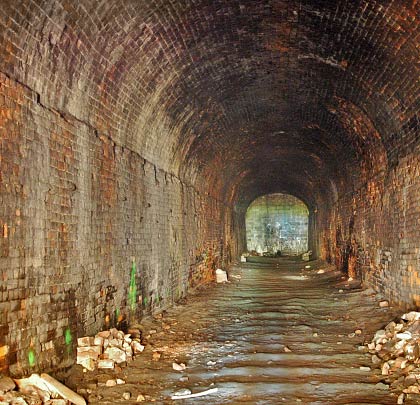

At 828 yards in length, the structure incorporated a rising gradient of 1:56 towards Whitstable and was only 65 feet below the surface at its deepest point. A series of financial crises ensured trains didn’t encounter it until 3rd May 1830 as its promoters went back to Parliament three times for authority to raise more funds. The track consisted of 15-foot fish-bellied iron rails on wooden sleepers at three-foot intervals, conventional stone blocks having been deemed too expensive.

Isambard Kingdom Brunel conducted experiments on the line in 1835, aimed at silencing critics of his proposals for the Great Western Railway, particularly the perceived dangers of operating a line through a steeply-graded tunnel, which was his intention at Box.

The C&W was divided into six planes and Stephenson recommended the use of stationary engines for the three inclines, with horse power on the level sections. However the promoters insisted on a locomotive for the shallowest incline, resulting in the procurement of Invicta from Robert Stephenson & Company. Unfortunately it was incapable of handling the 1:53 gradient to the south of Whitstable and a third stationary engine had to be installed in 1832. Modifications were carried out to Invicta during 1835 but these proved unsuccessful.

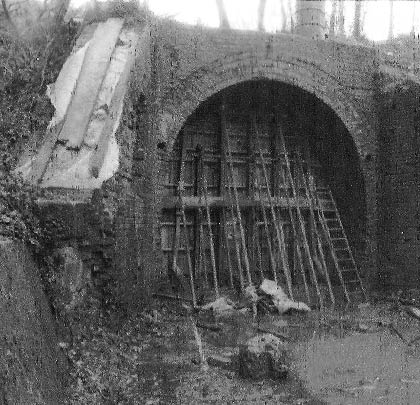

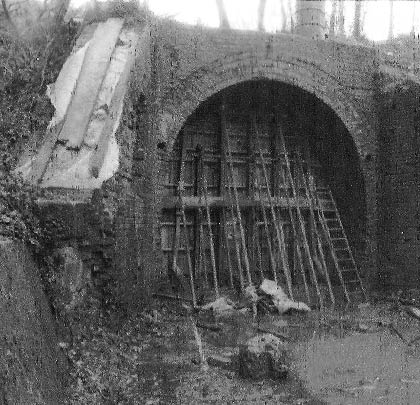

Three years later, following an exceptionally wet summer, inspections found cracking and subsidence at the tunnel’s north portal. To stabilise it, the crown of the arch was stripped and concrete puddling applied, buttresses built as reinforcement and the parapet lowered to improve drainage.

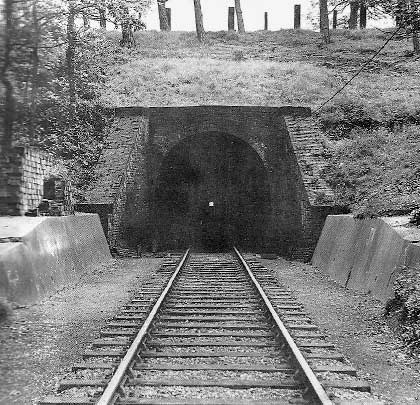

The C&W was leased by the South Eastern Railway in 1844 and the company set about relaying the track. The stationary engines were taken out of service two years later, with locomotives operating the line thereafter. However severe restrictions on motive power and rolling stock were created by the diminutive size of Tyler Hill Tunnel, measuring just 12 feet wide by 12 feet high.

Passenger services were withdrawn from 1st January 1931 whilst freight traffic ceased on 1st December 1952. The line was briefly reprieved in February 1953 due to flooding of the nearby London Chatham & Dover Railway. Track was lifted from within the tunnel a year later.

In 1963, the University of Kent – which was then being established – acquired the structure for £70. An inspection determined that it was safe to build over and part of the campus was subsequently erected on land above it. However a 1973 report found significant defects in the tunnel, including bulging of the vertical sidewalls. Tenders went out for the repair work but it was too late: on 11th July 1974, the Cornwallis Building was affected by subsidence, sinking 18 inches in about an hour. Responsible was a 30-yard collapse, filling the tunnel with brick and clay 260 yards from the north end.

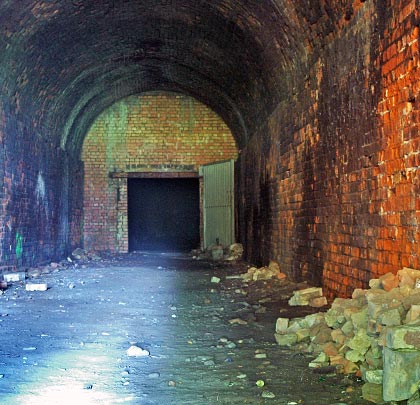

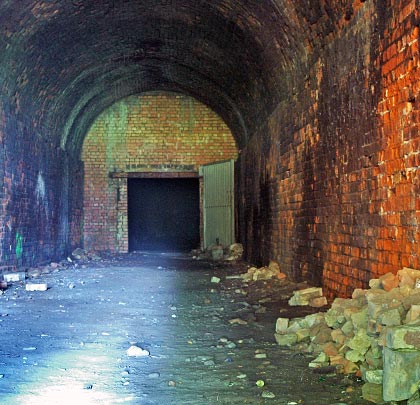

Part of the building was subsequently demolished and Pulverised Fuel Ash (PFA) pumped into the tunnel via a series of boreholes. A recent survey revealed this material to have settled, leaving a space of 100mm at the crown. Since the original work, a bulkhead has been assembled about 100 yards from the south end and further infilling carried out beyond it. A brick partition wall has also been inserted 30 yards in from the entrance.

The south portal, built in red brick, was the focus of a restoration project in 2009. Until recently, the north portal was in a particularly poor state due to a blocked land drain and tree growth. However these have now been felled, remedial works undertaken and the brickwork repointed. The portal features an elliptical yellow brick arch of four rings, wing walls with tooled ashlar blocks as copings.

Since 2009, the structure has been protected by a Grade II* listing.

(Andy Parrett’s picture is taken from Geograph and used under Creative Commons licence.)