Thurgoland New Tunnel

Thurgoland New Tunnel

Railway promoters kept parliament busy in 1836, depositing more than a hundred bills for its consideration and approval. Amongst these was the Sheffield Ashton-under-Lyne & Manchester Railway, led by Lord Wharncliffe, backed by 56 local bigwigs and guided by engineer Charles Vignoles. Over the course of that summer, Vignoles and Joseph Locke independently surveyed routes, coming together in October to reconcile any differences. Their joint plan involved a summit 966 feet above sea level at the eastern end of the three-mile Woodhead Tunnel.

To the south-east of Penistone, the meandering Don Valley demanded another – but much shorter – tunnel at 315 yards in length. Close to Huthwaite Hall, it accommodated two tracks on a generally curved alignment but the curvature was erratic due to failures in laying it out, varying from 20 to 100 chains in radius with straight sections in-between. As a result, the six-foot had to be reduced and the levels of the tracks made to differ in order to achieve minimum clearances.

Stone was used for both its lining and portals – the latter benefiting from buttresses either side of the entrance and bull-nosed voussoirs reminiscent of Great Northern architecture. No refuges had been provided when the first trains passed through in 1845.

At around 9:15am on 14th July 1855, a group of farm workers – employed by Mr Corbett at the Hall – “heard noises of a great disruption of the earth”. One of them ran to the tunnel and found it blocked by a collapse a few yards in from the south portal; he then proceeded to Thurgoland Station to report the emergency. All trains were stopped. Repairs to the affected section – which did not exceed 10 yards in length – were protracted by further falls of shale, loosened by ground water. At its peak, 500 men were involved in the recovery works, including 200 from Grimsby docks. The line was reopened after 10 days. Over the intervening period, men were required to walk over the summit whilst ladies were carried in Mr Corbett’s carriage.

Electrification of the Woodhead route was given the go-ahead in 1936. With accommodation of overhead line equipment (OLE) impossible due to the restricted structure gauge, the Sheffield-bound line was slewed onto its centreline whilst a second bore was driven alongside for the other track. Nationalisation of the railways occurred during the construction resulting in both LNER (1947) and BR (1948) datestones being fixed at its south end.

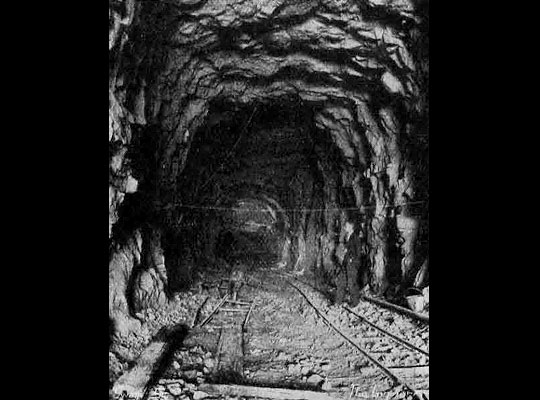

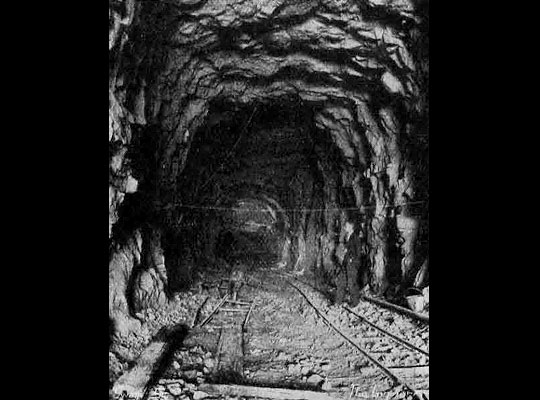

Concrete-lined but with masonry portals, the New tunnel features a tighter curve of 60 chains and is slightly longer than its neighbour at around 339 yards. It falls to the south on a gradient of 1:131. The OLE registration arms were fitted in recesses at the crown and identified by wall-mounted plates.

The tunnel demanded the excavation of around 70,000 tons of rock and earth. Work got underway in November 1946, but progress was slow owing to the almost continuous support needed for the poor rock. Labour shortages and winter weather conditions exacerbated the delays. The headings eventually met on 9th January 1948. In charge of the engineering were the chief engineer of the London & North Eastern Railway, G B Barton, and Sir William Halcrow & Partners; the contractors were John Cochrane & Sons Ltd.

Amidst much controversy, the Woodhead route was closed in 1981 but the Deepcar-Barnsley Junction section – which included the tunnel – survived until 16th May 1983.

Since then the original tunnel has been backfilled at its southern end and a wall built across the north entrance. Inside, two sections of brick arch are apparent close to the south portal, presumably for strengthening purposes. A distinct flattening of the arch can be seen at these locations. A row of cable hangers – which formerly carried cables along the east sidewall – have been cut off, but still in-situ at the haunches are short lengths of rail used to support the OLE. A collection of old railway furniture, including a solitary concrete sleeper, evaded the salvage crews.

The new bore is now lit and forms part of the Trans Pennine Trail.

Click here for more of Roger5450’s pictures.

Click here for a gallery of pictures showing Thurgoland Old Tunnel.