Spinkhill Tunnel

Spinkhill Tunnel

Like many others, the Lancashire Derbyshire & East Coast Railway had foundations built on coal. When plans were developed to establish collieries on his estate in the 1880s, William Arkwright determined that the best way to fully exploit them was by laying an independent railway, driving eastwards and westwards from his seat near Chesterfield. The original Act authorised a main line from Warrington to Sutton-on-Sea, an extensive network of branches and a new docks complex.

Landowners generally welcomed the plans and Arkwright acquired rights to the proposed Newark & Ollerton Railway to form the core of his new line. Whilst Robert Elliot-Cooper, a preeminent civil engineer, was appointed to take charge of construction, critical to achieving corporate success was Emerson Bainbridge, himself a distinguished engineer and local mining mogul who advised on the best route. He had immediately seen the potential behind Arkwright’s big idea.

The railway emerged from its Parliamentary passage in August 1891, however the associated euphoria soon subsided when the necessary capital proved difficult to secure. The Great Eastern Railway stepped in, seeing an opportunity to cut itself a slice of the region’s lucrative mineral traffic. The price was a severe curtailing of the scheme, with activity focussed only on the line’s central section, connecting Chesterfield to the Great Northern & Great Eastern Joint Railway at Pyewipe, as well as an 11-mile branch to Beighton, south-east of Sheffield.

Ground was broken in Chesterfield on 7th June 1892, the work having been divided into three contractual parts. By far the heaviest was that secured by Messrs S Pearson & Son; this comprised the Chesterfield-Warsop section – including several viaducts and more than 3,100 yards of tunnel – and the Beighton branch. The latter, which pushed northwards from Langwith Junction, was key to capitalising on Sheffield’s heavy industry.

As late as 1896, the branch looked set to terminate in the middle of nowhere. However that year saw an Act passed for construction of the Sheffield District Railway, diverging from the Beighton branch near Barlborough to reach Attercliffe, the city’s northern industrial centre. The Midland Railway then intervened, offering the use of its metals for part of the route and creating a connection to Attercliffe at greatly reduced costs. The Beighton branch suddenly became strategically important.

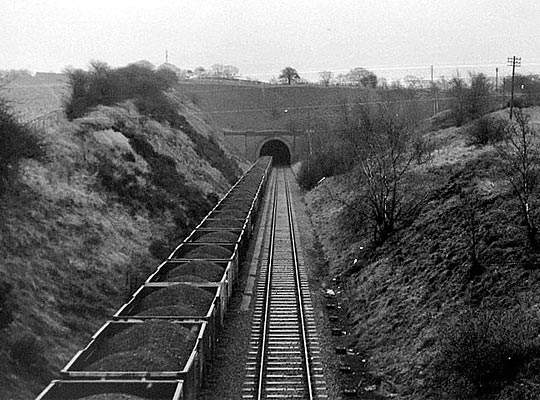

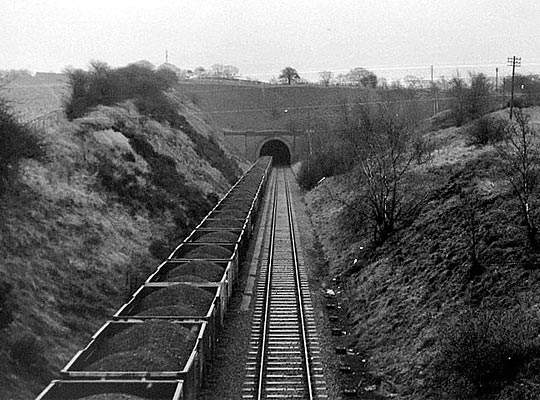

The 9 mile post was found in Spinkhill Tunnel, extending for 492 yards and the most significant engineering work on the line. From the south, trains approached through a vertically-sided rock cutting; at its end stands the minimalist portal – predominantly brick-built but featuring stone copings and oversail. Stubby triangular wing walls push outwards, parallel to the track. The arch face exhibits only four brick rings, good ground conditions having been encountered here. A construction shaft was also sunk towards this end of the tunnel, although there is no longer any sign of it. The p-way drain splits in two at the entrance to discharge, via stoneware pipes, into ditches in both cesses.

For almost 200 yards, the tunnel curves to the west on a radius of around 36 chains; thereafter it straightens. The gradient throughout is 1:100, falling to the north; the maximum width is 26 feet and height 22 feet. Horseshoe-shaped in profile, the lining at the crown varies in thickness between 1 foot 10 inches and 4 feet 10 inches. This considerable variation was a function of the very heavy ground encountered through the northern half of the tunnel. To resist the lateral forces, 158 yards of invert was built inwards from the portal, with a second section of 8 yards needed near the middle of the tunnel. Refuges are inserted every chain on alternate sides, offering an extra 18 inches clearance from passing trains.

The north portal is more substantial, with the loose cutting slopes held back by curved wing walls. These are typically 6 feet 6 inches in thickness at their bases. Behind the headwall is a brick channel with gratings at either end, allowing water to reach the track drain via 6-inch diameter pipes.

Unlike at the south end, the sides of the northern approach cutting are battered to improve their stability. However services through the tunnel were disrupted in February 1937 due to a slippage of the bank on the east side, forcing the introduction of single line working. Gangs were carrying out remedial works when there was a collapse on the opposite side, completely blocking the line. A replacement bus service had to be laid on.

Construction was attended by a typical collection of accidents. On 14th January 1896, a labourer named Burke was moving a wagon in the tunnel when he lost control of it due to defective brakes. This resulted in his shoulder being crushed between a prop and one of the wagon’s buffers. He was taken to a navvy hut where Dr Devine tended to his injuries.

The tunnel entered operational service on 21th September 1898 and was absorbed into the Great Central’s empire nine years later. Local passenger services were withdrawn at the outbreak of World War II but the route continued to be used for excursions and diversionary purposes. The section of line through the tunnel closed to freight traffic on 9th January 1967, however the tracks up to the north portal remained in use until 1984 for the shunting and storage of colliery wagons.

Precious little railway furniture remains in the tunnel. Towards the north end are two brackets on the west sidewall which might have held a gong, providing an audible indication of Spinkhill’s Home signal. The tunnel is generally dry – except at the northern entrance – but numerous weep holes have been inserted through the lining, allowing substantial quantities of ochre to accumulate; there is also extensive water staining of the brickwork at the crown.

Structurally the tunnel appears in very good condition, however cracks have developed in one of the buttresses at the north portal and a bulge is apparent at the haunch on the west side. Wedges have been inserted into the brickwork in an effort to prevent this worsening.

The tunnel is privately owned and, over the winter, is used for cattle storage.