Scotland Street Tunnel

Scotland Street Tunnel

Authorised by Parliamentary Acts of August 1836 and July 1839, the Edinburgh Leith & Newhaven Railway inaugurated its 1¼-mile horse-drawn service from Canonmills to Newhaven on 31st August 1842, establishing a passenger and goods link between the city and a port on the south bank of the Forth.

Following a name-change to become the Edinburgh Leith & Granton, the line was extended to reach a new harbour at the latter named place in 1846 and a branch to Leith opened two years after that. 1847 brought two significant developments: horse power gave way to steam and services were pushed deeper into the city by means of the 1,007-yard Scotland Street Tunnel.

This was an undertaking of very considerable scale and complexity as it had to be driven beneath a thoroughfare that ran northwards from Princes Street, through the New Town to the reach the terminus at Canonmills. To allay fears regarding the impact of the works on adjacent properties, Edinburgh’s Sheriff appointed respected civil engineer George Buchanan to oversee the works on the city’s behalf. Thomas Grainger looked after the engineering for the railway company whilst William Paterson acted as resident engineer.

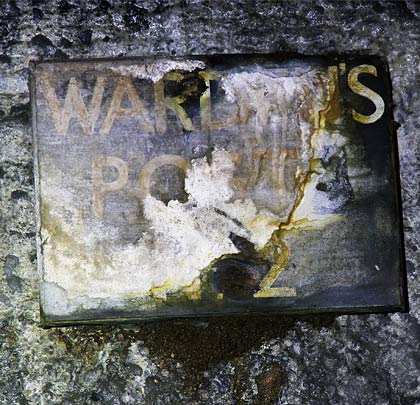

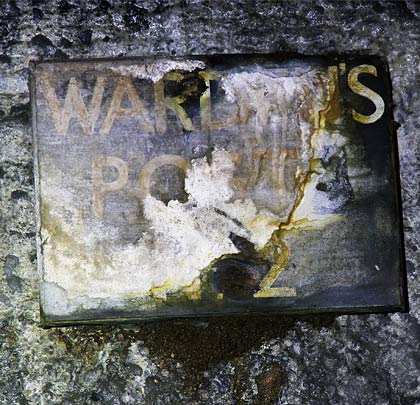

Work on the tunnel got underway in earnest early in 1844 with the sinking of five construction shafts. At 88 feet in depth, the first to be sunk was located outside the National Bank in St Andrew Square, 165 yards from the south portal. No.2 shaft, 89 feet deep, was 207 yards further along North St Andrew Street. Located at the top of Dublin Street, No.3 shaft was sunk to a depth of 59 feet. About half-way down was No.4 shaft, 48 feet in depth. And on the south side of Drummond Place was the most northerly shaft, just 39 feet deep.

Six-feet square headings were driven outwards from the bottom of these shafts, progress with which proved quite speedy. Early on the morning of 29th November 1844, two miners were working at the face of the heading to the south side of No.3 shaft, their aim being to affect a junction with the heading from No.2 shaft, the contract for which had been completed seven months or more earlier. With no work taking place therein, it had filled with water.

Unbeknown to the miners, the direction of their heading had been incorrectly surveyed, such that it was passing to the east side of the one it was intended to meet. Between them and the huge volume of water was a narrow partition of clay. At about six o’clock, the men’s ganger and superintendent arrived to check on progress. About half-an-hour later, a great roar was heard by those above ground, followed by a powerful surge of water which fiercely struck the roof of the shed enclosing the shaft top. All four men perished and floods engulfed properties as far north as the Canonmills terminus, 500 yards away.

Contracts for excavating and lining the southern section of tunnel were awarded to John Barr & Co early in 1845. By March, the tunnel was complete from the south end to a point beyond No.1 shaft, with rapid progress being made elsewhere. Three months later, the only parts yet to be finished were between Nos. 2 and 3 shafts, and to the north of No.5 where a ridge of whinstone was hampering operations.

The northern portion, extending for about 250 yards beneath Scotland Street, was built under a separate contract by cut and cover methods due to the sandy nature of the ground, although there is evidence that attempts had been made to sink one or two shafts here. The work involved progressively excavating the roadway to a depth of about 40 feet, inserting the lining and then reinstating the ground. To facilitate this, the old Custom House in Drummond Place had to be demolished. June 1846 brought this phase to its completion. Structural work on the bored tunnel was concluded in September; Captain Coddington carried out an inspection for the Railway Board in April 1847 and the tunnel opened on Monday 23rd May.

Scotland Street Tunnel measures 24 feet wide, rising towards Princes Street at 1:27. The severity of this gradient meant that traffic had to be hauled up to the new terminus at Canal Street on an endless rope. Mr Hawthorn provided a stationary engine for this purpose. Trains heading down to Canonmills were arrested by brake wagons. On 4th June 1847, after less than two weeks operation, the rope broke and services through the tunnel were suspended for ten days.

The Edinburgh & Northern Railway took control of the Edinburgh Leith & Granton on 27th July 1847, with the North British assuming control in 1862. It established a link into Waverley (then known as North Bridge) Station six year later and brought closure of the route through the tunnel to passengers. Scotland Street depot at Canonmills continued to serve goods and mineral traffic which arrived from the north.

During the Second World War, the tunnel was returned to funtionality, acting as an air-raid shelter for 3,000 residents of central Edinburgh and the London & North Eastern Railway’s emergency headquarters and command centre. For this latter purpose, a collection of brick and timber buildings were erected against the west sidewall, with communication links provided to key railway facilities – stations, depots, signal boxes and the like. Toilet blocks and blast walls were also built.

Peacetime brought further activity in the tunnel. It hosted a mushroom farm in the Seventies and was subsequently taken over by a car dealer to store vehicles. More recent proposals for its reuse have included the installation of a power generation plant and incorporating it into an Edinburgh Metro network. None has been progressed.

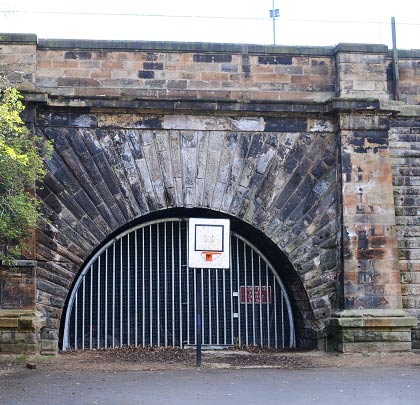

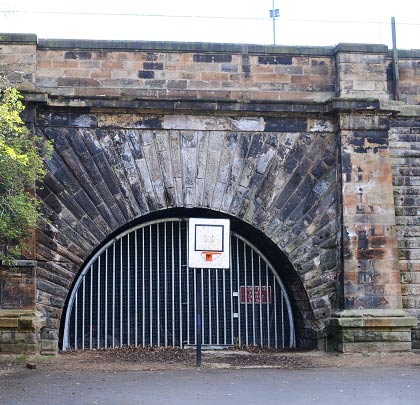

The north portal of the tunnel, now fenced up, looks out onto a park and play area. In keeping with other portals on the line, it features long rusticated voussoirs tapering outwards to meet ashlar buttresses. Beyond these are retaining walls, all topped by a string course beneath ashlar coped parapets.

At the north end where cut-and-cover methods were used, an ashlar lining was erected; brick becomes predominant through the bored section although occasion lengths of ashlar sidewall are encountered. It is clear from the extensive localised mineral deposits that there has been significant water ingress, although the floor of the tunnel is generally dry. A white circular deposit is visible at the crown, probably caused by seepage from a construction shafts. At one location, cracks have opened at both haunches over a length of about 20 feet, resulting in the formation of hinges.

No refuges are provided although, near the south end, there is a single arched entrance on the west side leading into a small unlined chamber. Further north, there is a square opening in the same wall, topped by a decaying lintel. An assortment of furniture – tablets, brackets, timber supports – are attached to sidewalls.

A concrete blockwall has been built about 20 yards from the former location of the south portal, beyond which the surrounding area has been developed. However a gate in the north wall of Waverley Station provides access to a metal tube which leads into the tunnel.

Click here for more of James’ pictures.

Click here for more of K-Burn’s pictures.

October 2014

October 2014