Rhondda Tunnel

Rhondda Tunnel

Through the 1870s, increasing coal production in the Rhondda severely tested the handling capabilities of its monopoly carriers, the Taff Vale Railway and Cardiff Docks. Return journeys typically took two days. This background of crippling congestion spurred the merchant folk of Swansea – where new coal shipping facilities had opened – to develop plans for the Rhondda & Swansea Bay Railway (R&SBR).

Incorporated on 10th August 1882, the company proposed a shorter export route via the Afan valley but, to reach it, the line would first have to overcome a 1,700 feet high natural barrier, Mynydd Blaengwyfni. Set that task was engineer Sydney William Yockney; his father, Samuel Hansard Yockney, had acted as engineer and manager for the contractor at Box Tunnel, bringing him to the attention of Isambard Kingdom Brunel for whom he went on to fulfil a number of other tunnel projects.

Work on the R&SBR was split into three contracts, No.3 being awarded to William Jones of Neath. Included within it was the construction of Rhondda Tunnel, the second longest wholly within Wales and critical to the success of the venture. Completion was stipulated within three years. Serving as the resident engineer was William Sutcliffe Marsh.

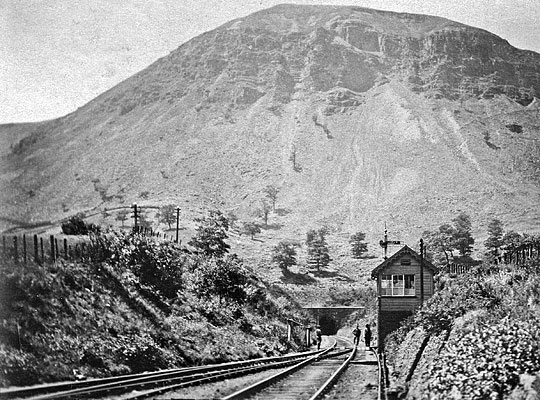

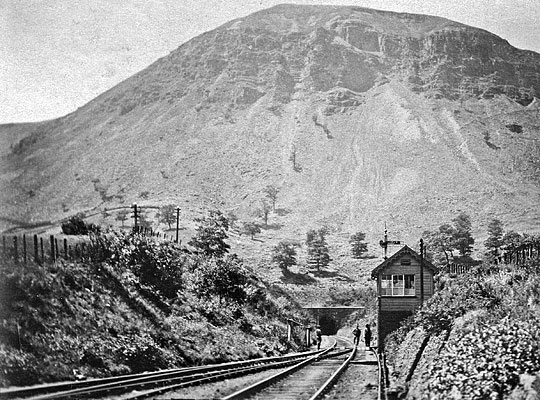

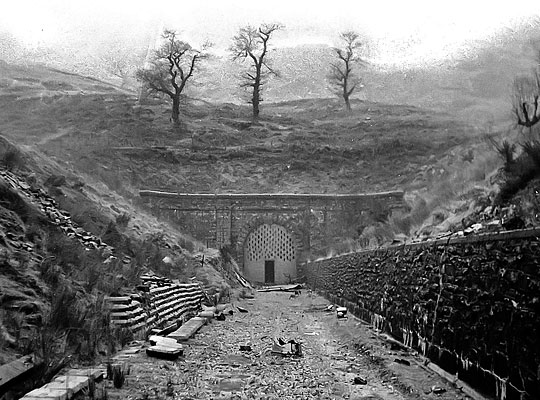

Preparatory works began on site in the autumn of 1883 – including the sinking of a shaft at the western (Blaengwyfni) end – but the official breaking of ground was delayed until 30th May 1885. Thereafter excavation of the approach cuttings was pushed forward, although difficulties securing land at the eastern (Blaencwm) end – on which an entrance shaft was to be sunk – prevented substantive progress there for another 15 months.

Driving of the headings from the western shaft got underway in September 1885. After a very slow start, Yockney reported only marginal improvement over the subsequent months despite good ground conditions and little water ingress. In Jones’ view, the criticism levelled at him was unwarranted – citing the issues over land acquisition – but the engineer clearly felt that the works were not properly organised or resourced. Either way, the main heading was being excavated through sandstone at a rate of about 40 yards per month; “only very moderate progress” as far as Yockney was concerned.

With ground cover exceeding 900 feet, the conventional approach to expediting progress in lengthy tunnels – the sinking of intermediate shafts – was deemed impractical. However the miners did benefit from rock drilling machines, operated by compressed air which was generated by a pair of horizontal engines and stored in an iron tank before being passed into the tunnel. The machine’s exhaust acted as effective ventilation at the working face.

The drills’ arrival prompted a considerable upturn in fortunes, with the heading advancing thereafter at a rate of about 75 yards per month. Matters improved further when the contractor gained access to the outstanding parcel of land at Blaencwm, allowing work to begin on the shaft. The eastern heading was first pushed forward in November 1886.

Despite the miners’ industry, alarm bells were ringing loudly early the following year as progress started to slip; according to Jones, this was the function of a manpower shortage and the underground springs encountered towards the tunnel’s eastern end. Reluctantly, the company pushed back the contractual completion date to 31st July 1889.

It wasn’t until 16th March that year – with only 20 weeks to go – that the headings finally met. Yockney reported that the levels were out by just half-an-inch whilst the line was perfect, a remarkable result considering the length of the drives; he attributed it to “the care and skill” of Mr Marsh. The event was signalled by the firing of cannon and, four days later, the contractor entertained a hundred navvies to supper, song and recitals at a nearby hotel. But the glory was short-lived for the Tunnel Driving Company, subcontractors to Mr Jones. In December 1889, an extraordinary general meeting heard Chairman Tom Brown assert that it was “unable to continue in business by reason of its liabilities”.

Inevitably, the tunnel claimed more than just corporate casualties. John Harris, 24, killed by an explosion; William Shod, a haulier, run over by a wagon and fatally injured; Isaac Watson, 36, also succumbed to dynamite. And then on 22nd January 1889, news of a huge rock fall spread across the district; seven deaths were reported. Although an exaggeration, the reality – two victims – proved no consolation to the families of George Lever, a 28-year-old miner, and labourer George Smitherham, known to everyone as “Soldier”. Gangs of men laboured for many hours to extricate their bodies from the debris.

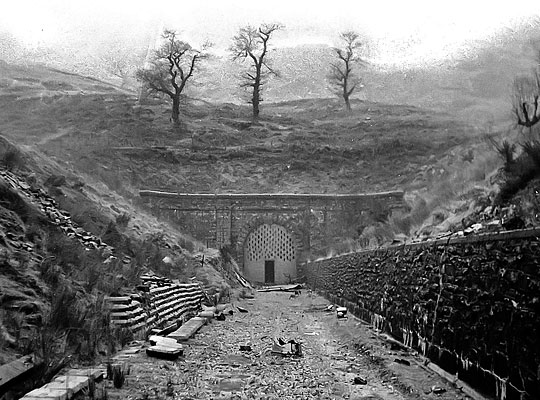

With the tunnel’s full excavation falling to just 98 yards per month – less than half of the rate required – the company dispensed with William Jones’ services in September 1889, bringing in Messrs Lucas & Aird from Westminster. Employing more than a thousand men to finish the line, they set about erecting new accommodation huts at both ends of the tunnel and, for four months, workers therein benefited from electric lamps. The western end was lengthened slightly, presumably due to instability of the cutting slopes.

A contractor’s engine became the first to pass through the full length of Rhondda Tunnel on 17th March 1890. Seven weeks later, with Yockney confident of a tick in the box, Colonel Rich attended to fulfil his inspection duties for the Board of Trade. He expected to find the tunnel fully lined, but it wasn’t. So before he would pass it as fit for passenger traffic, 753 yards of brick arch had to be hastily inserted, springing off arched concrete sidewalls. Operations resumed the following day, Lucas & Aird having already prepared for such an eventuality. Completion came just 54 days later, allowing the tunnel to start earning its keep on 2nd July 1890.

Wise practice in mining areas was for railway companies to buy pillars of coal that supported significant structures. Failure of the Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway to do so resulted in Bolsover Tunnel sinking by eight feet in 60 years. The R&SBR fell into the same trap of short-term economics, the upshot being areas of worsening distortion resulting from seams being worked both above and below Rhondda Tunnel.

Between 1938 and 1957, steel ribs were installed over a distance of around 220 yards at the east end and through two sections totalling 170 yards about half-a-mile in, the intention being to resist inward movement of the haunches and consequential pushing-up of the crown. Speed restrictions were imposed and several lengths of arch were relined as loose material fell onto the track; settlement of 15 inches was recorded in just 12 years. All this was exacerbated by considerable water ingress close to the east portal which extensively washed out the mortar.

In 1967, severe distortion was observed near the 2¾ milepost – around a third of the way through from the west end, close to a geological fault. So rapid was its deterioration that the engineer closed the tunnel on safety grounds on 26th February 1968. This was supposedly a temporary measure whilst a decision was made on the future of the line.

Three months later, a special inspection revealed a 9-inch bulge on the north side of the arch over a distance of 100 feet, with signs of the stone lining being crushed and a hinge at the crown. As a result, it was decided to erect timber cribbing – now known as ‘the cog’ – from 2 miles 61 chains 57 feet to 2 miles 62 chains 63 feet, a distance of 72 feet. A second inspection in October 1969 found that the distorted section had extended by 9 feet.

After much prevarication, the Ministry of Transport cited a decline in usage and the provision of a bus service as justification for the formal withdrawal of passenger services in December 1970. A cynic might suggest that the tunnel’s estimated minimum repair cost of £105,000 also had an influence.

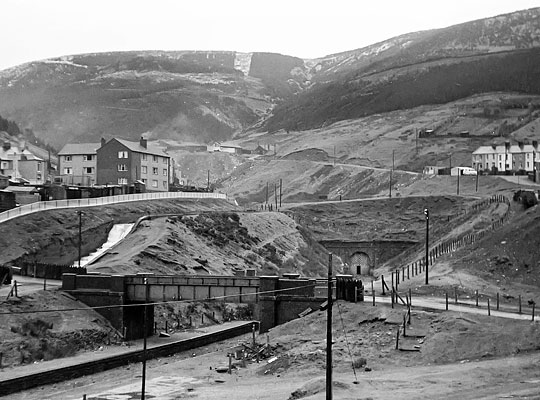

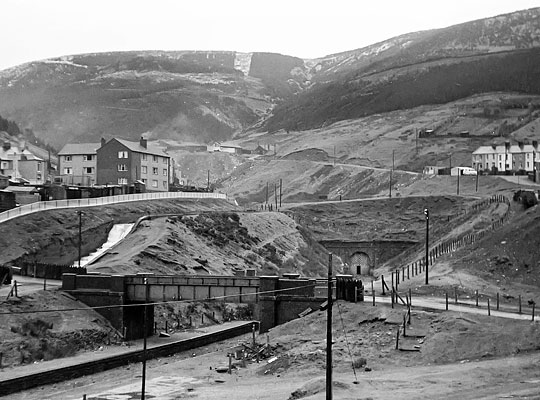

For ten years, the tunnel was largely left to its own devices. Then, with locals persistently breaching its protective blockwalls, contractors infilled the approach cuttings on behalf of the local authorities. At the western end, a double-diaphragm wall was erected adjacent to the tunnel’s only ventilation shaft, creating a sealed section of about 90 yards in length. At the other end, an access shaft was created using precast concrete rings, although no-one officially descended it for 35 years.

In September 2014, 19 locals assembled at The RAFA Club in Treorchy to discuss plans for the east portal’s cover stone – which had recently been discovered under a bush – to be rescued, restored and put on display. One of those in attendance suggested that they should campaign for the tunnel to be reopened as a walking and cycle route. Thus, the Rhondda Tunnel Society was established to progress this ambitious aspiration.

Engagement from the Welsh Government and other relevant bodies has been positive, and a detailed examination of the tunnel took place in spring 2018 with a view to developing a repair scheme. It was concluded that, from an engineering perspective, all defects could be rectified and managed. Based on this finding and the associated costing, a decision will be taken as to the viability of transferring the structure’s ownership from the Department for Transport, a pre-requisite of the reopening proposal being moved forward.

In August 2018, the Welsh Government awarded Rhondda Cynon Taf Council £250,000 to help it develop its plans for the reopening of both Rhondda and Merthyr tunnels.