The story of Mierystock Tunnel: The Big Dig

- Author: Graeme Bickerdike

- Source: The Rail Engineer magazine

- Published: August 08

The story of Mierystock Tunnel: The Big Dig

Never have crusty old relics enjoyed so much exposure than on Channel Four’s archaeological extravaganza ‘Time Team’…and that’s just the presenters. Haven’t these people heard of hairdressers? Still, they perform a great service. Unearthed remains bring revelation, opening our minds to folk’s trials and tribulations through the ages. Though few can find function in the 21st Century, not all end up as museum pieces.

June 1872 witnessed Cardiff contractor J E Billups cut the first sod of a new railway connecting Gloucestershire’s Severn & Wye line with the Great Western’s network at Lydbrook. Along this artery, the Forest of Dean’s mineral wealth would flow to markets beyond.

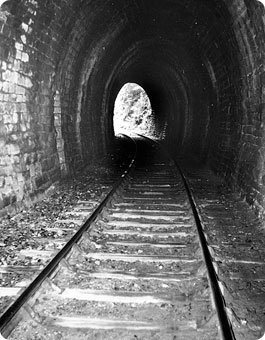

It was an unremarkable route, save for Lydbrook’s stone and wrought iron viaduct which dominated its valley until the wrecking ball of progress ripped through it in 1965. Further up the 1 in 50 gradient, the line vanished into a tight, steep-sided cutting where the 242-yard Mierystock Tunnel lurked. Therein struck tragedy during 1893 when a ganger surrendered his life to a locomotive. Five years on, fallen rock caused a derailment in the northern portal’s shadow. Runaway trucks added more colour to the picture.

Logic dictates that a railway’s prosperity closely follows that of the industry it is built to serve. So when mining in the forest began its decline in the late 1920s, local branch lines suffered an unsurprising fate. The descent to Lydbrook Junction had its death sentence passed in 1956.

Prior to closure, local lad Frank Barnett spent many-a-day picking lineside blackberries which he sold by the bucket load to “the man on the horse and cart”. Only a fool entered the cutting for fear of encountering the daily goods service – this appeared at ten o’clock and scuttled away before lunchtime. Instead, he would climb up to a nearby quarry where wild strawberries grew. Snakes, slow worms and lizards provided entertainment.

On 11th July 1960, a final train braved Mierystock’s darkness, propelling a brake van. Frank’s mate Keith Allford was aboard, surveying the scene ahead of him with camera in hand. To the rear, demolition contractors busied themselves tearing the track up.

When the health and safety brigade came to power in the Seventies, its attention soon turned to the abandoned tunnel and cutting. The former had a breezeblock wall erected just inside its entrance whilst the latter was obliterated by 30,000 tonnes of colliery waste.

The trackbed was once again harnessed as a servant to industry – this time leisure and tourism – in 1995, attracting walkers and cyclists to the forest, particularly during summer months. A half-mile bypass escorted this traffic around the tunnel, crossing the busy A4136 Gloucester-Monmouth road on the brow of a hill. Near misses and one hit are on record.

Photo: Frank Barnett

Frank often fulfilled his grandfatherly duties by taking his offspring’s offspring along the old line, reciting tales of the buried hole in the hillside. He wondered how it was doing. One day, he turned up at Keith’s house with a madcap scheme – they should dig a path down to expose the dated keystone. Off he went to buttonhole landowners at the Forestry Commission.

His claim of a hidden tunnel met with disbelief; plans to expose it found bemusement and reluctance. But Frank had garnered support in the form of his brother George and friend Michael Bennett. These four, high-mileage gentlemen would not take no for an answer.

On 1st February 2005, hard graft was heard rumbling through the trees. Financed from their own pockets and driven by a mate called Dave, an excavator had begun to chew the earth beneath a rocky outcrop. A stone emerged; shovels were set to work. Brushes cleared filth away. Willpower slowly teased masonry from its grave; the portal breathed again. By the week’s end, proof of Mierystock’s forgotten history peered skywards from an 18-foot crater.

Photo: Four by Three

The fearless foursome was about to sit back and bask in the glory of a job well done when a gift horse galloped over the horizon, staring them straight in the mouth. ITV’s People’s Millions – a competition backed by lottery cash – was offering £50,000 grants to worthwhile community projects. Instead of cycle path users playing Russian roulette on the road above the tunnel, why not take them via a vehicle-free route underground? The infilled approach cutting proved a compelling obstruction unless it could be dug out.

With a neighbour’s help, Frank set to work on the application form, popped it in the post and forgot about it. Some weeks later, a TV crew came calling. A promotional film made the case for Mierystock. Viewers voted in their thousands to make the venture substantially richer and watched Frank presented with the cheque live from a local pub. When the euphoria had subsided, the scale of their mission hit home. The small print stipulated that funds must be spent within 12 months. The clock started ticking in November 2006.

It was J E Billups’ good fortune that it had not been compelled to navigate today’s bureaucratic quagmire. The tunnel might never have been bored otherwise. Planning consent for the cutting’s excavation demanded an environmental impact study; archaeological surveys took place; lizards had to be catered for, so too bats. The world of officialdom descended from high places. Despite deafening encouragement from all-and-sundry – and the receipt of additional funds – no stone had been turned with just seven weeks remaining. The boys felt under pressure.

Autumn 2007 saw the green light belatedly switched on. A drainage channel was opened, temporary paths laid and a diversion built for the cycleway. On 1st October, two 10-tonne dumper trucks rolled onto site along with another excavator. Three labourers sliced layers of waste from its resting place, transferring it to the quarry on top of the hill. At a snail’s pace, the past was exhumed while Frank and his pals looked on. Anxiety gave way to relief when the clock struck midnight – the deadline had been met and the cutting could see the light of day again.

Of course, only half the story has yet been written. The next step is to secure support and funding to reopen the tunnel, light it and lay a cycle-friendly surface. Inaction is currently speaking louder than the fine words of authority, but Sustrans’ positive noises are a cause for real hope.

removed 30,000 tonnes of colliery waste.

funding can be found to open a

cycle path through the tunnel.

Surely, the determination of Frank, Keith, George and Michael must be a lesson for us all. It would be a travesty if backs were turned on the benefits which the tunnel has to offer. Breaking down the road barrier between the forest to its south and industrial heritage to the north would entice more people to the area whilst saving a life or two.

Whatever the final outcome, the fab four have made their mark. The cutting will serve as their worthy legacy. Generations to come have been afforded the opportunity to stand and marvel at J E Billup’s substantial endeavours.

More Information

| Walking the Wye Valley | Peter Dean traces local railway lines |