Merthyr Tunnel

Merthyr Tunnel

The Vale of Neath Railway (VoNR) was a logical extension of the strategic opportunity offered by the South Wales Railway (SWR) which cut through an area rich in minerals. The development of ironworks and collieries up the valley towards Aberdare created an aspiration for quicker and easier access to the new line, as well as nearby ports. Hence a railway eastwards from Neath was promoted by Town Clerk Henry Simmons Coke. Support proved forthcoming from the SWR’s directors with whom he discussed the idea in May 1845; their key stipulation was that broad gauge must be adopted.

As proposed, the first ten miles from Neath featured relatively gentle climbs; thereafter they became more severe as the summit was reached, before falling to the terminus at Aberdare. One section involved a gradient of 1:50 for 4½ miles. To reach the ultimate destination of Merthyr, a branch would have to be pushed under the mountainous ridge separating the Cynon and Taff valleys. Thomas Joseph surveyed the route, acting for engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel.

IKB reassured the Parliamentary Committee that traffic would not be unduly compromised by the steep gradients and authority for the line was granted by an Act of 3rd August 1846. The company could raise share capital of £550,000, however this proved difficult due to the turmoil on the money markets that accompanied the end of ‘Railway Mania’. As a result, the South Wales Railway agreed to take about £127,000 of unallocated shares, an arrangement ratified by Parliament in 1847.

The first construction contract was awarded during that summer. Tenders for the tunnel and approach cuttings on the Merthyr section – which comprised Nos. 3, 4, 5 & 6 contracts – were requested in December, the successful submissions coming from Messrs Fowler, Sharp, Jones and Davies. They undertook to complete the work in 21 months, but a delay of five months was then incurred whilst financial settlements were agreed with the landowners at both ends.

By August 1849, the contractor for the south-west (Abernant) end of the tunnel – responsible for two shafts and the connecting headings – had defaulted, whilst work in the approach cutting at the other (Merthyr) end was at a standstill due to a dispute between the contractor and his creditors. Progress was better through the north-east half of the tunnel where two deep shafts had reached half way; two others were complete and almost 500 yards of heading driven.

But the shareholders were getting restless. In order to earn revenue, the company decided to focus its efforts on the branch to Aberdare, the engineering for which was less arduous. An inaugural train for the directors and their friends ran from Neath on 23rd September 1851. Public services started the following day and were immediately well patronised, with three trains each way most days. The journey time was 70 minutes. Goods traffic started in December, but silting at Swansea docks and delays in completing wharves at Briton Ferry meant that coal trains didn’t run until April 1852.

During this period, work on the tunnel was largely in abeyance, with only piecemeal progress being made by the company’s agents. The headings advanced at a meagre average rate of one yard per day.

Either side of the summit, the two deepest shafts were abandoned when only partly sunk. The next deepest – at 275 and 354 feet – were more than 1,200 yards apart and a single heading was driven to connect them, 7 feet by 6 feet in size. Fans blew air into the workings through horizontal troughs; however this arrangement proved inadequate and choking powder smoke lingered after shots were fired. It was therefore decided to install a 1-inch diameter pipe – connected to a cistern at the top of a shaft – which split in two at the bottom and terminated in rose heads, each with six small holes drilled in it. The enormous pressure forced water out like a blast of condensed steam, the current of air in the troughs thereafter attaining a speed of 600 feet per second, sufficient to clear the smoke.

Early in 1850, the company directors had been told that a further £7,000 was needed for work on the shafts and headings. They agreed to the investment and, in May 1851, William Ritson – who had constructed Pencaedrain Tunnel, further up the VoNR – was appointed to complete the tunnel. By this time, the six shafts had been sunk to their correct level and just 230 yards of heading was left to be driven under the highest point of the hill.

At its south-west end, the tunnel had already been opened-out to full size, with enough space to accommodate two broad-gauge tracks; however, for speed and economy, the remainder was excavated for only one line of rails. The sum spent on the tunnel eventually exceeded £60,000, but it started to produce a return on 29th October 1853 when the first commercial service passed through.

As built, Merthyr Tunnel had a length of 2,497 yards and was ventilated by two shafts, 410 yards from the south-west end and 877 yards from the north-east end. Approaching from Abernant, trains climbed a 1:81 gradient which eased to 1:411 about 60 yards into the tunnel. A curve to the north of 30 chains radius continued as far as the first shaft. After 610 yards, the gradient began to fall – first at 1:91, then 1:116 – followed by a section at 1:100 for about half the tunnel’s length. The last 200 yards was level. A curve to the south of 80 chains radius was encountered for 300 yards before a short straight section took over on the approach to the exit.

During its first 50 years, Merthyr Tunnel was subject to considerable subsidence as a result of coal being worked beneath it. Miners could hear trains passing above them and a number of vehicles derailed due to problems with the track. The settlement occurred in waves, progressing from one end of the tunnel to the other, with some sections being displaced by as much as 10 feet. No movement was recorded at points where wide faults were located so, here, the invert had to be lowered to maintain the correct track geometry.

In 1870, the Cardiff Times reported that “Many complaints may be heard in this locality of the way in which the carriages jump up and down as they pass through this tunnel. Several times of late the writer has seen numbers of females in nervous trepidation in consequence. They fancy the state of the rails is not satisfactory, and bearing in mind the number of serious railway accidents that have occurred of late, they work themselves into a state of excitement and alarm.”

On the evening of 7th January 1874, the driver and fireman of a goods train leapt from the footplate about 300 yards from the Abernant end after observing an obstruction ahead. The tunnel had collapsed and the locomotive half-buried itself in the debris before coming to a stand. A large workforce attended and, despite continued falls of brickwork, the line had been cleared by midday on the 9th January. However, just as a passenger train was about to depart Merthyr, news came through that about 100 yards of the tunnel had fallen in. A visit by the chief engineer revealed the extent of the damage to be far worse than had originally been recognised.

Substantial repairs were carried out, the void being packed with bundles of brushwood before a stone arch was erected and a further five rings of brickwork turned below it. On 20th February, Colonel Rich attended for the Board of Trade, examining the tunnel from one end to the other with the intention of allaying public fears about the stability of the structure. Heaps of debris were retained at the trackside for his inspection.

The company undertook further strengthening works around the site of the collapse over the autumn of 1877, a secondary lining being installed. Unfortunately, on 11th November, the morning shift’s exertions were halted when the tunnel suddenly gave way over a distance of about 100 yards, depositing thousands of tons of material onto the track. The failure was attributed to heavy rain. Two shifts of men worked around the clock at both sides of the blockage but further falls were reported over the next few days. Traffic did not resume until the following summer.

Whilst the collapses had a commercial impact, there was thankfully no loss of life. However, just months after the 1874 repair had been completed, the tunnel played a bit part in an accident that could have killed many.

At 3:26pm on 16th May, a passenger service operated by the Brecon & Merthyr Railway (B&MR) pulled into Merthyr Station which was shared with the VoNR. Those on board casually disembarked.

Around 20 minutes earlier, a goods train hauled by two engines had left the adjacent yard for Swansea, climbing to reach Merthyr Tunnel up gradients as stiff as 1:50. Also on board were three guards and a brakeman. David James, one of the drivers, described “a sudden lurch” about 150 yards into the tunnel as the coupling to 22 laden coal wagons snapped. In the rear van, Robert Lewis put the brake on hard and strapped it; he then jumped down and succeeded in applying the brakes on several wagons, running alongside the train for about 200 yards before it left him behind.

The runaways gathered speed down the incline and, after a mile and a quarter, entered Merthyr Station, smashing into the back of the stationary passenger train. The locomotive was propelled through the buffers, into the building and across the road where it was embedded 4 feet into a retaining wall. 52 people sustained injuries ranging from cuts and bruises to fractures requiring amputations; one woman subsequently lost her life.

Merthyr Tunnel’s unpredictable operational history came to an end on 31st December 1962 when the line through it was closed.

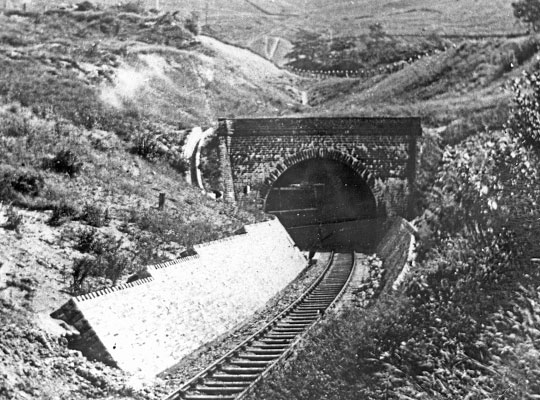

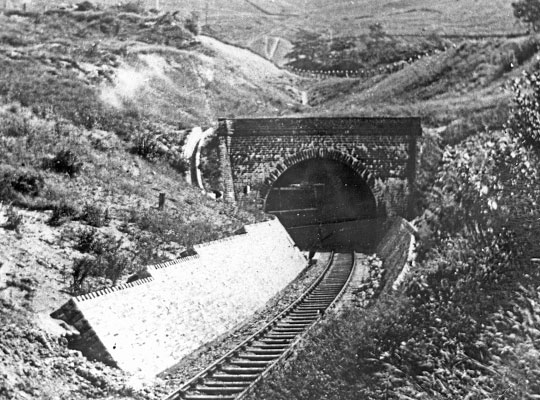

The south-west portal is stone-built, its headwall turning outwards at both ends to form triangular wing walls. Framed by the original voussoirs is a secondary brick lining of six rings. The north side of the approach cutting is held back by a retaining wall, battered back to an angle of 55 degrees.

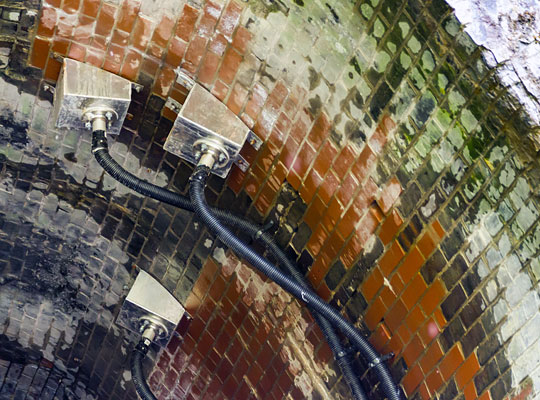

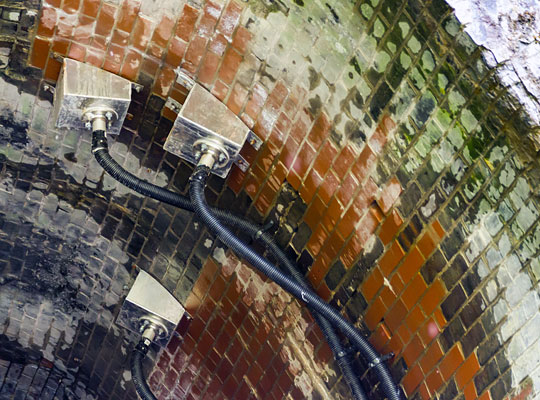

Until recently, the first 40 yards of tunnel comprised brick sidewalls supporting a series of steel arches and laggings. These are now encapsulated in sprayed concrete. Beyond this point, structure gauge is reduced by four additional rings of red brick, heavily coated in soot and packed with stone to the rear. Three timber frames are then found, probably erected to support centring for arch repairs.

After 160 yards, the tunnel becomes wide enough to accommodate a double track layout. Two small buildings occupy the trackbed on the north side, both with fire places. Opposite, a refuge reveals the brickwork to be only two rings thick, but at the back is the arch of another refuge – at a lower level – with stonework above. This suggests a relining scheme has taken place here, together with changes in the invert.

The tunnel abruptly becomes single track width 222 yards from the entrance. The lining is predominantly stone through the remainder of the curve, but with a strip of brickwork at the crown and patches in the bottom half of the sidewall. As the alignment becomes straight, the first bricked-up ventilation shaft introduces running water, the pans and pipes which previously discharged it into the drain being missing.

For 25 yards beyond the shaft, the tunnel’s section becomes circular with the installation of a corrugated steel liner, grouted behind with foamed concrete. This was presumably prompted by eccentric loading which had caused the arch to distort. Shortly after, the invert appears to have been gradually lowered by as much as 5 feet, resulting in changes of profile with lengths of high arch and over-tall refuges.

Located at the midpoint is a platelayers’ cabins, equipped with a fireplate, benches and whitewashed walls; there was a smaller one 680 yards from the entrance. The remaining part of the tunnel offers fewer features, although four hidden shafts are passed. Numerous open catchpits allow a glimpse of the drain at the toe of the Up sidewall. Refuges are numerous and of variable depth; many have open backs, exposing rock or coal.

A concrete arch has been cast at the base of the former ventilation shaft which is sprung off brick buttresses built up to the haunch. New pans and pipes have been installed to manage the water ingress. Signs identify three more hidden shafts as the exit is approached, daylight being introduced after a short curve.

The north-east portal is an imposing stone-built structure, pushed into the end of a steeply-sided approach cutting. The arch face presents six brick rings with some spalling and separation.

In August 2018, the Welsh Government awarded Rhondda Cynon Taf Council £250,000 to help it develop plans for the reopening of both Rhondda and Merthyr tunnels as cycle paths.