The story of Oakamoor and Marlborough tunnels: The Sleeping City

- Author: Graeme Bickerdike

- Source: Rail Engineer magazine

- Published: March 09

The story of Oakamoor and Marlborough tunnels: The Sleeping City

Whatever happened to kids TV? I don’t ever recall Valerie Singleton feeling the need to surprise Blue Peter guests with an aerial bombardment of gunge; neither were the ear drums of Jackanory’s audience ruptured by John Grant bawling his way through another tale about Littlenose, the inquisitive cave boy. Yes, I know…Mr Grumpy has surrendered to middle-age again!

The weekly must-see for this child of the Seventies was Animal Magic which generally involved Johnny Morris adding silly voices to Bristol Zoo’s collection of cute and cuddlies. A fruit bat could often be spied hanging upside-down behind him – a creature with something of a spectral reputation courtesy of its role in horror films. Scooby Doo didn’t do it any favours either.

in the most unlikely of places.

Our ignorance about bats – a function of their nocturnal lifestyle – colours most people’s judgement of them. They are in fact intelligent creatures with a complex social life. Britain hosts 16 species (a 17th suffered extinction recently), all of which eat insects and are much smaller than you might think. Although their numbers have declined drastically through loss of habitat, this fall has been arrested somewhat by the protective harness of legislation, education and conservation.

Bats are far from blind but their eyes are of little use when hunting at night, hence their highly-sophisticated echo location system which allows them to catch prey and dodge obstacles in total darkness. If your mind’s eye pictures one in flight baring its teeth, this is not an act of aggression. More likely, the bat is emitting a high-pitched call, the echoes of which it uses to create a three-dimensional map of its surroundings. Very clever stuff.

With food in short supply, they hibernate through the winter, dropping their heart rate and body temperature. This helps them preserve fat. But where do they disappear to? Prepare to re-enter the world of railway engineering.

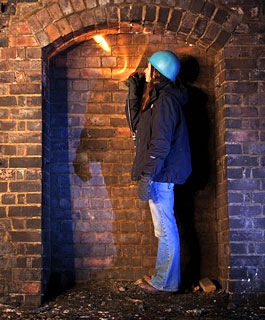

It’s Saturday morning. Frost has encased the world; brass monkeys are right to look worried. Yet Helen, Paul, Rose and another Paul have rejected warming retail therapy. Instead, they’ve chosen to spend a couple of hours combing a disused railway tunnel for hidden, sleeping guests.

The 497-yard Oakamoor Tunnel, a product of the North Staffordshire Railway, was driven through a hillside just west of the village after which it is named. To its north is the tranquil Churnet Valley. A crossing keeper’s cottage – itself a bat roost – sits in the shadow of its southern portal. Opened in 1849, this section of line was given back to nature in 1965.

The structure was notoriously wet and, without maintenance, time has inevitably taken its toll – the brickwork is badly spalled in places and repair work shows itself throughout. Towards both ends, dozens of small holes have been cut into the lining. A couple of bricks deep, they offer bats perfect winter accommodation – cold but stable temperatures with high humidity. The tunnel, cared for by Staffordshire County Council, is secured at both ends so the chance of disturbance is minimal.

Helen is a bat’s best friend, combining her voluntary role as chair and conservation officer for the Staffordshire Bat Group with her day job, an ecology consultant. She has worked in operational as well as disused railway tunnels and appreciates what Victorian engineers unwittingly created for these misunderstood creatures. She’s also thankful that we’re now more clued-up about issues which impact upon them. “People have started to understand how vulnerable bats are to things like building works, shotcreting and repointing of bridges and tunnels. Authorities don’t tend to do that now without first having bat surveys done.” The railway is no exception – several of our major consultancies are involved in this area of work. Perhaps you should give them a ring about that project you’re planning for next winter.

of Oakamoor’s refuges.

Nine bats had booked into Oakamoor – four Brown Long-eared (a widespread but declining species) and five Natterer’s. Not a vast population; village-like you might say. But in Wiltshire, another forgotten tunnel has been transformed into a sleeping city – one of the most significant bat hibernation roosts in Europe.

A railway was born five years after the Marquis of Ailesbury succumbed to the financial advances of the Midland & South Western Junction Railway. His was the land through which the company hoped to lay a three mile line, bridging the missing link in its strategically important route from Cheltenham to the port of Southampton. In its absence, the M&SWJR had been paying an annual ransom of £1,000 to run over nearby GWR metals.

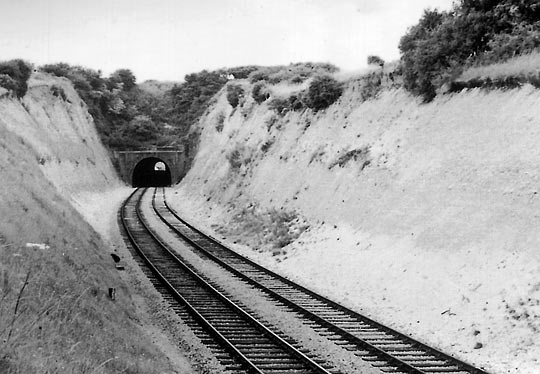

The chalk barrier of Posterne Hill, towards its northern end, was conquered with deep cuttings and the 647-yard Marlborough (aka Savernake) Tunnel. A train first emerged from it in 1898; there were no more after May 1964.

Photo:

Bluebell Railway Museum Archive

/J J Smith

If furry tenants subsequently moved in, they were left largely to their own devices until the early Nineties when a local bat group established a regime of winter surveys. In January ’93, 41 bats were found in the tunnel; many others were presumed to be hiding behind the lining. A year later, that figure has risen to 57. With evidence of disturbance from human traffic, it was decided that the site would benefit from some protection.

Although dumped chalk spoil substantially plugged the southern entrance, the northern portal had remained fully open. Over two bank holidays in May 1994, volunteer labourers supported by a local builder sealed the tunnel with concrete blocks. The northern wall, which is over 6 metres high at its centre, incorporates a grille used for both bat and inspection access. At the other end, a more modest barrier of 1.5 metres was erected, again featuring a grille.

Securing the tunnel has greatly changed its micro climate. Before the walls were put up, the temperature at its centre broadly matched that outside. Now it varies by only one degree either side of 8C, even during the summer. Relative humidity has risen from 80% to over 95%. The stiff breeze which once blew through has been calmed. Conditions couldn’t be better.

Bats seek out snug hibernation crevices, something old tunnels often have in abundance. But Marlborough’s facilities have been upgraded by the attachment of wooden planks, corrugated plastic, roofing tiles and bat boxes to the lining. All 38 refuges now have full-width plywood sheets fitted within them, offering additional shelter.

It’s an investment of time and effort which has paid huge dividends; the trend in winter visitors has enjoyed a steady rise. From a low point of 15 in December ’93, the tunnel welcomed 274 bats in January 2008. Seven different species have chosen the structure as their hibernation roost.

Ongoing responsibility for the site’s maintenance rests with the Wiltshire Bat Group, headed by Steve Laurence who’s been active in bat conservation and research for 20 years. He took part in the tunnel’s first winter survey and has managed its protection and development since 1994. The structure has claimed a significant part of his life.

In January, I joined Steve as he led an 11-strong team into the gloom to record numbers and species, something he does three times every winter. It’s a painstaking business, with noise and illumination levels kept to a minimum. A group of four people – all verifying each other’s observations – examine one side of the tunnel and its various attachments for bats. Results are checked and collated by a fifth person, the group leader. The final count is then passed onto Steve who misses all the action, standing in the middle with his clipboard and ladder. An identical process is going on at the other side of the structure.

The reason for this approach becomes apparent when you understand just how difficult bats can be to spot, squeezing themselves into some ridiculously tight places. At least one was found sleeping in a perished mortar joint.

A few bats have forearm rings which are read by licensed bat workers – that apart, they are left undisturbed as the law requires. After seven hours, the job was done. And what an occasion it turned out to be, with the previous record count smashed to oblivion. A remarkable 383 bats were in residence including a lone Serotine which is not supposed to be found deep within underground sites. This one had clearly not read its text book.

Facing a future of terminal decline, Marlborough Tunnel’s fortunes have been turned around in a manner which was unimaginable when the railway moved out. Today it is a renowned ecological success story. As Steve acknowledges, “Railway tunnels are proving massively important to bats as they adapt to a loss of natural habitat, and I’m very grateful to the people who put in all that effort to build them.”

Many thanks to Helen Ball and Steve Laurence for providing information and site access for this story.

More Information

| Swindon’s Other Railway | Photo of train leaving Marlborough Tunnel |

| Swindon’s Other Railway | Gallery of plans and contemporary photos |

| Exploring the Potteries | Photo of train leaving Oakamoor Tunnel |

| Valley Wanderings | Pictures from the Churnet Valley |