Mapperley Tunnel

Mapperley Tunnel

Construction of the Great Northern’s Derbyshire & Staffordshire Extension was driven by a desire to exploit local coal reserves without their competitiveness suffering due to the high transportation charges imposed by the mighty Midland Railway. Thus an Act of 1872 was passed which sanctioned a disruptive new line across the city, such was the eagerness in business circles to ensure speedy progress. The Midland’s leverage diminished when the Extension’s first section opened in 1875.

The chosen route might have minimised capital costs but this was still a difficult endeavour involving numerous viaducts and tunnels. Richard Johnson, the GN’s chief engineer, designed the works whilst W H Stubbs patiently fulfilled the role of resident engineer. For construction purposes, the route was split into two contracts, Joseph Firbank fulfilling the western section whilst Benton & Woodiwiss delivered the east end. To give scale to the challenge, the line demanded the excavation of two-and-three-quarter million cubic yards of rock and earth; 30 million bricks were used as well as 1,400 tons of wrought and cast iron.

At 1,132 yards, the longest of the tunnels by some distance penetrated a ridge to the north-west of Gedling, approached through a cutting 70 feet in depth which was crossed by a brick aqueduct. Mapperley Tunnel’s construction was expedited by sinking six shafts, steam engines being deployed at each for hoisting up the spoil. This was then taken away to form a nearby embankment. Three of the shafts were subsequently retained as ventilators. Track level was 210 feet below ground at its deepest point.

As is to be expected, attending the work was a catalogue of misadventure – minor, major and fatal. Here’s a random sample. Miner Charles Daniels was crushed to death by a fall of earth in February 1874. In July of the same year, a lad named Shepperton suffered a severely crushed hand. Two months later, William Tucker was taken to hospital with smashed hand and badly cut head after some bind fell on him. And a lump of rock landed on 24-year-old navvy George Longthorn in August 1875, causing serious back injuries.

On 23rd January 1925, a collapse triggered by mining subsidence brought down a 12-yard section of roof, blocking the line with around 150 tonnes of debris. Whilst repairs were carried out, traffic was diverted along the Nottingham Suburban Railway which took a roughly parallel course further to the west. The tunnel was repaired but the continuing effects of subsidence resulted in the imposition of speed restrictions during the 1950s. Closure came on 4th April 1960.

Today the west portal is buried and the tunnel backfilled for a distance of 510 yards, as far as the centre shaft. This – with its tower of tipped rubbish – and the eastern shaft remain open; the other is capped and located under the drive of a new house off Gedling Road. The shaft linings are supported on cast iron curbs, inserted into the arch.

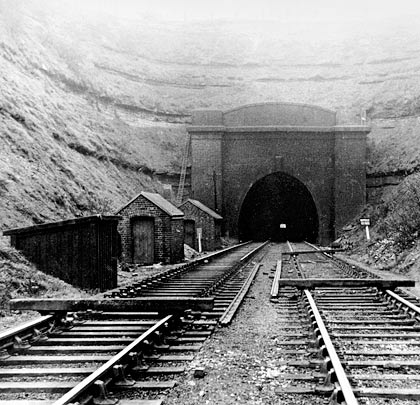

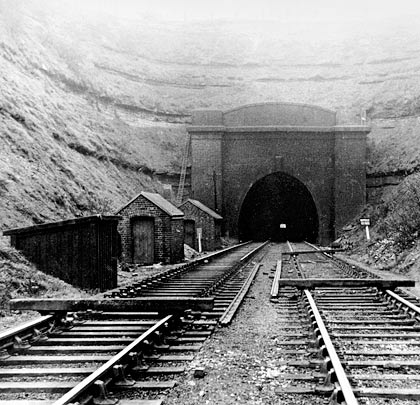

The east portal is an imposing brick structure although it looks rather lost at the end of the vast cutting. It comprises two substantial buttresses either side of the entrance and an unusually high headwall. The copings are ashlar, as is the projecting keystone. Exhibited by the arch face are ten brick rings, needed to withstand the ground forces being exerted on the tunnel.

Immediately beyond the portal, the lining – which necessitated the manufacture and laying of five million bricks – is in a poor condition, with short sections of sidewall having collapsed. A 12-inch square beam – formerly one of three – still straddles the tunnel between its haunches, presumably inserted to support a working platform.

Extensive spalling afflicts the brickwork further in, a function of the considerable water penetration. This has however washed away much of the soot. For the majority of the tunnel’s length, the crown of the arch benefits from the additional support of iron ribs – inserted at the haunches – and poling boards. The refuges are plentiful, generously proportioned and often open a window on the exposed rock behind. Accessed via catchpits, an overworked 12” drain runs beneath the centreline.

In July 2007, the East Midlands Development Agency issued a tender for investigation work in the tunnel – which is now a recognised bat roost – connected with the redevelopment of the Gedling Colliery site, a former seat of industry which was served by the railway until closure in 1991.

(Railway Dave’s photo, taken from Flickr, is used under Creative Commons licence.)