Mansfield Road Tunnel

Mansfield Road Tunnel

For many years, the Manchester Sheffield & Lincolnshire Railway sought an independent line to the capital as almost 70% of the coal it transported had to complete its journey southwards on the metals of rival companies. In 1873, it promoted a Bill for the construction of several joint lines in association with the Midland Railway, the intention being to reach St Pancras, but this was strongly opposed by the Great Northern. Powers to extend its own line from Sheffield to Chesterfield were sought in 1888, however opposition from the Midland stifled this plan. A year later, a Bill was deposited for a more extensive scheme, linking Beighton with Annesley via Staveley, and a branch to Chesterfield. This was passed and first welcomed traffic from the Derbyshire coalfield in 1892.

In the meantime, engineers Charles Liddell, Edward Richards and Edward Parry prepared Parliamentary plans for a 92-mile extension to London, comprising a line from Annesley to Quainton Road where it would form a junction with the Metropolitan Railway. A Bill was presented to Parliament in 1891, but this was rejected. The following session brought an amended scheme, including an extension at the southern end to reach Marylebone.

Royal assent was granted at the end of March 1893, with construction contracts let in September 1894 and the first sod cut on the 13th November. By July 1898, the line had been sufficiently readied to allow the running of coal trains and the route was formally opened to passengers on 9th March 1899. By this time the company had changed its name to the Great Central Railway and spent around £7 million on the project, the equivalent of £7.4 billion today.

For engineering purposes, the line was divided into sections, with Parry being appointed as engineer for the Northern division (Annesley to Rugby). Fulfilling the construction contracts alongside him were Messrs Logan & Hemingway (Annesley to East Leake), Henry Lovatt (East Leake to Aylestone) and Messrs Topham Jones & Railton (Aylestone to Rugby).

The line entered Nottingham through a series of tunnels or covered ways, emerging into the open at Victoria Station where a huge cutting offered a floor space of 12¾ acres. Reaching 58 feet deep, it demanded the excavation of almost 600,000 cubic yards of sandstone.

Immediately to the north, trains entered the 1,189-yard Mansfield Road Tunnel, encountering a reverse curve through its southern half, then a straight section and finally a westerly curve before exiting at Carrington Station. The gradient throughout is 1:132 and the tunnel reaches a depth below ground of 120 feet where Forest Road East/Mapperley Road crosses its line.

Large enough to accommodate the contractor’s locomotives, 12-foot square bottom headings were progressed from four shafts, in Corporation Yard, the Forest Recreation Ground, Huntingdon Street and at the junction of Mansfield Road/Alfred Street. The operations were watched by crowds of interested spectators, but those shafts affecting the highway proved a great inconvenience to residents, business folk and pedestrians; these were fenced off behind unsightly timber hoardings.

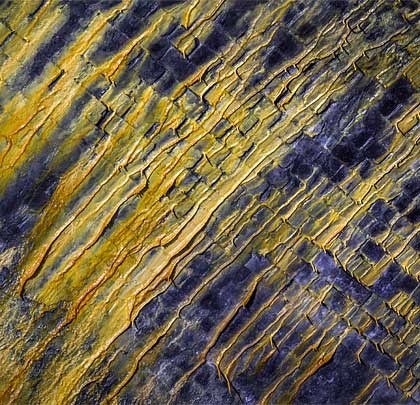

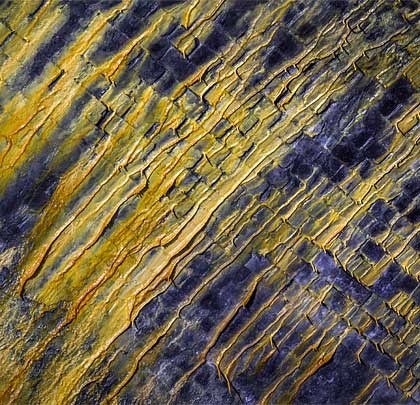

Top headings were driven from break-ups between the shafts, the work being carried out from temporary platforms erected over the bottom heading. The lining was turned in lengths varying from 12 feet 6 inches to 18 feet, the centring being supported on rock left at the sides for this purpose. As the tunnel passes through bunter sandstone, no built sidewalls were necessary; instead the arch springs off benches cut into the rock. Throughout the brickwork is built in Old English bond, using common bricks faced in Staffordshire brindles. The arch is 30-34 inches thick, with a rise of 8 feet 6 inches, giving a clearance of 20 feet above rail level.

Every 22 yards, refuges were cut into each side of the tunnel; three botheys, each 10 feet square, were also provided at intervals of ¼ mile for the platelayers to use during rest breaks or for the storage of tools and materials. These incorporate seating ledges.

Although the Great Central’s passenger service ended in 1966, traffic continued to use the tunnel for another couple of years, exiting at its southern end to pass through the developing dereliction of Victoria Station. Today the station site is occupied by a soulless multi-storey car park.

The tunnel has been sealed by a concrete blockwall at its northern end, the cutting beyond it having been backfilled. Access is maintained by means of a shaft, the opening to which is in front of an office block. The south portal, brick-built and with its attractive datestone, is being lost to vegetation; the entrance is blocked by wooden sheeting which has fallen into disrepair.

Inside the tunnel is dry and relatively benign. Numerous relics of the railway’s signalling system remain in-situ, such as mountings for signal heads, their associated ladders, a wooden troughing route along the Up-side wall and assorted hooks and pulleys. There is also the typical accumulation of modern detritus.

Further development of the nearby shopping centre has been approved by Nottingham City Council which is likely to result in access to the tunnel’s south end being rendered impossible.