The story of Little Weighton Cutting and Drewton Tunnel: Over The Top

The story of Little Weighton Cutting and Drewton Tunnel: Over The Top

Chaos reigned at Hull docks. Congestion stifled the prosperity which King Coal was bringing to Grimsby – the rival port across the Humber. Local businessmen were up in arms and plotted a scheme to smash the monopolistic dominance of the North Eastern Railway, which controlled every train – coal and otherwise – heading to the city. Their plan was not spawned by railway mania – this was about competition.

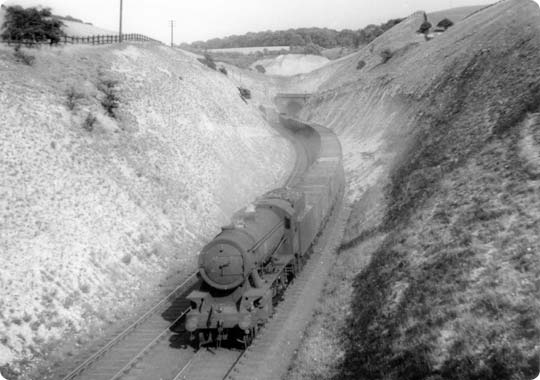

Photo: Neville Stead

The Hull, Barnsley & West Riding Junction Railway and Dock Company had a title as gargantuan as its goal. To save time, it was later renamed the Hull & Barnsley Railway. With the two most sensible routes already occupied by the NER, it chose to cut its new line through the heart of the Wolds, linking the Yorkshire coalfields with its own deepwater dock.

William Shelford, the line’s engineer, mustered all the technology that the late nineteenth century had to offer. Construction work on Alexandra Dock was a round-the-clock operation thanks to electric lighting – the first engineering project in Britain to benefit from it. Pneumatic drills made tunnelling easier. Steam navvies were deployed. But finance proved as taxing as the terrain and the company was struggling to make ends meet even before the line was completed.

Five-and-a-half million pounds later, the 53 mile route was ready for business. The first goods traffic pressed the sleepers on 20th July 1885 with the passenger service welcoming customers a week later. One of the last substantial pieces of Britain’s railway jigsaw was in place.

The 12 mile section through the Wolds was a back-breaker and contributed significantly to the line’s steep average cost of £59,000 per mile. Cuttings and tunnels had to be excavated, but the area’s loose chalk proved difficult and frequent landslips occurred. More than 8,000 men helped build the line, living in camps and rioting regularly. The largest of these temporary communities – boasting shops and a mission chapel – was at Riplingham on top of Drewton Tunnel.

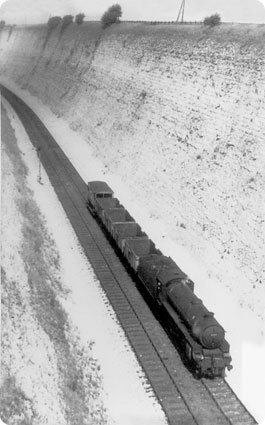

Colour photos: Four by Three

Hull-bound trains emerged from 2,114 yards of gloom at the line’s summit, whilst an 83 feet deep cutting – known by the navvies as ‘Big Hill’ – concealed their passage down the other side. Little Weighton sat proudly between these two immense achievements.

When Stan and Audrey Cash came into the world, the village was home to around a hundred folk, many of them farm workers. He always had Woodbines. She had a glint in her eye (and still has). Marriage was inevitable. “The railway was the only way out” says Stan. “There were no buses. You could get on a steam train at eight o’clock and be in the centre of Hull by twenty-past. You’d maybe go to the pictures. Back into town every other week to see Hull City, go to the Tiverley Theatre or the Gainsborough Fish and Chip restaurant. My grannie used it – she made butter and sold it on Hull market.”

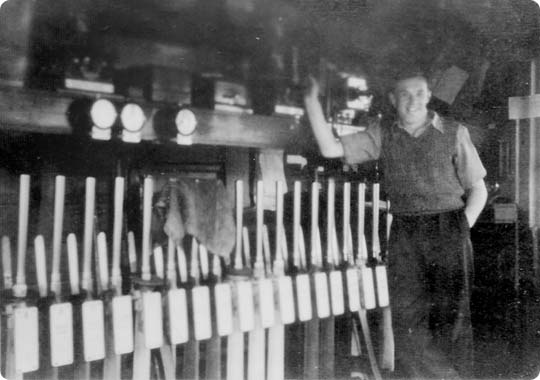

Ron Slater was also born in Little Weighton and became a railwayman whilst still a boy. In the spring of 1945 he took an examination in block signalling and, a year later, was installed as signalman at his home station – a role his grandfather had once fulfilled. By this time he was just 19.

“When I first took it on, we were on three shifts” he remembers. “I had two colleagues and a relief for the day off. I was the only one from Little Weighton and Harry King – who taught me railway signalling – was from Skidby. He’d been there a long time.”

Indeed he had – Mr King was the main man. He was on duty on 9th May 1930 when, according to his entry in the Occurrence Book, “I saw a man running from Drewton Tunnel waving his arms. I immediately placed all signals to danger after being advised that the Drewton East signal cabin was on fire and likely to cause an obstruction.” It was never rebuilt – traffic levels didn’t warrant it.

Little Weighton’s box backed onto a cutting and was a sun-trap during the summer. The station was a bustling enterprise, with a goods yard, cattle dock, coal sidings and quarry line. Another quarry was served by a siding up towards the tunnel. “You could be reasonably busy but not dashing around – we had time to sit and read a book!” says Ron. “There was a mixture of passengers and goods – mainly mineral trains from the West Riding. The passenger service would stop at eleven o’clock. And, on the night shift, it was just coal trains – empties going west and loaded trains heading east into the docks. We were open 24 hours-a-day for quite a spell.”

Photo: Hull & Barnsley

Railway Stock Fund

Photo: Hull & Barnsley

Railway Stock Fund

The cutting first impinged on Ron’s working life during the severe winter of 1947. As he recalls “We were down to single line working. The east winds were blowing and the snow drifted over the top of the cutting and brought the chalk down, blocking the line into Hull. The back end of a coal train – three or four wagons and a brake van – was stuck in there until it thawed.” The platelayers had a tough time, clearing drifts from the point-rodding and signal wires only for the snowplough to come along and cover them again.

Little Weighton survived that winter thanks to the railway. “There was one line open and that’s what kept us alive” declares Audrey Cash. “Normally the co-operative man used to come and collect your orders, but he couldn’t get in. So he sent all the groceries up on the train.”

Photo: Ron Slater Collection

A signalman’s life is solitary and, for the most part, Ron Slater was left to his own devices. A brief consultation with Mad Jack at control would resolve occasional pathing conflicts. “If a goods train was fully loaded coming up the gradient from South Cave – making heavy weather of it – you’d have to put him into the siding” he recalls.

On one such occasion, a light engine was scurrying up the hill behind a passenger train. The passenger went through and Ron cleared the signals for the engine. But the driver of a coal train, waiting in the siding, saw the signal change. “Why he thought it was for him I don’t know, but he set off. And of course there was a catch point. I heard this bang. Next thing I knew, the fireman was coming up the cabin steps. ‘We’re off the road!’ he said.” A crane was summoned. Patience was a virtue amongst goods train drivers and, at times, in short supply. They were not averse to dirty looks and colourful language.

Like many tunnels, Drewton had a climate of its own. It could be very wet and perishingly cold. During the winter, icicles would form – often several feet long – and the first train through on a morning would collect a batch in its tender. One loco had its cab window smashed.CAPTION: Two spectacular shots from

It was also the scene for Ron’s only heart-stopper. A young signalman at South Cave – the next box back – had authorised a driver to pass an intermediate signal at danger following a track circuit failure. But this was almost a fatal error – a heavy goods train was still in the section ahead, making painfully slow progress up the hill. “So I was there waiting at the signal box door – listening. If he’d caught him up in the tunnel there would have been a heck of a mess. Then suddenly I heard it – ‘chuff chuff’. I had the signal off, waiting for him to go through and as soon as the engine passed the signal, I put it back to danger. The brake van was passing the cabin as the other train came into view. By, it shook me up!”

But a bigger shake-up was on the cards. Hull’s coal commitments were waning and, during the 1950s, British Rail hatched a plan to divert all remaining traffic over the easier NER route. The Hull & Barnsley’s decline was swift. Little Weighton’s passenger service bit the dust on 1st August 1955. Ron Slater had already left to pull the levers at Beverley North but, before the year was out, had said his goodbyes to the railway and was working on a farm.

Photo: Ron Slater collection

Stan Cash was not a happy man. “It should never have been closed” he claims. “East Yorkshire put buses on but they used to shake your bones. From here to the bus station in Hull would take an hour.” The village certainly lost out but the sums just didn’t add up.

Through freight traffic ended in December 1958, marking the tunnel’s retirement. A shuttle service from Hull fed the coal yard until 1964 but, that summer, Little Weighton’s rail connection was finally severed, having survived less than 80 years.

Despite forty years of neglect, Drewton still exudes magnificence and is now the protected home to a colony of bats. Chalk-falls have almost engulfed one entrance but the eastern portal sits proudly at the head of its cutting, resisting encroachment by landfill. It’s a different story east of the village. Half-a-million cubic metres of household and industrial waste are slowly consuming Little Weighton Cutting. Within a decade, all traces of it will be gone.

The Hull & Barnsley only enjoyed a short life and the harsh truth is that it failed to meet its promoters’ considerable expectations. But it was a triumph in so many ways and no amount of landfill can obscure the role it once played at the heart of a small Wolds community.

More Information

| Hull & Barnsley Railway Stock Fund | Body maintaining surviving H&B rolling stock |

| Andrew Grantham | Recent photos of tunnels through the Wolds |

| Ley Transport | Images of the Hull & Barnsley |

| Martin Limon | A Victorian White Elephant |