Elliott Simpson recalls his Sixties incursion into Law Tunnel: An underground adventure

Elliott Simpson recalls his Sixties incursion into Law Tunnel: An underground adventure

One of my early childhood memories was of my dad lifting me up to look over a wall to see the entrance of the railway tunnel “under” the Dundee Law – in fact it started just below the crest of a shoulder of the hill. That night, in my dreams, we found another entrance behind the High Kirk, which stands more or less directly above the tunnel, and we found an ancient steam engine in the middle of the tunnel. I think that, subconsciously, I was still searching for it when I later explored the tunnel, only to find its spitting image 40 years later and 400 miles away in the Canterbury Museum.

In the mid-1960s, I took a series of photos showing the remains of the railway which ran from Dundee to Newtyle. The stimulus to start looking for it – and particularly for the buried north end of the tunnel – was probably a conversation with the mother of a former school friend who said that, in her youth, it had been possible to walk through the tunnel, although she had never done so.

I had heard that there were traces of the trackbed out in the countryside and, within the town, there were several buildings which sat at odd angles to the adjacent roads because they had been built to align with the track. I was surprised to find that one of these buildings was my father’s own printing works where I used to watch the steam trains shunting the trucks on the Fairmuir marshalling yard and another was the laboratory block at the Royal Infirmary where I started my career as a biochemist.

The railway was fairly frequently referred to in the local newspaper, the Courier. Typical of these items was the following, which had found its way into the envelope in which I kept the photos.

The train with a sail

Did you know a railway train with a sail once ran from Dundee?

In Auchterhouse Old and New, by the Rev J Kirkland Carneron and M Oliphant Valentine, the authors say this about the old railway from Dundee to Newtyle (the first in Scotland): “On the level sections of the line traffic was brought by horse haulage. When the wind was favourable, speed was accelerated by the hoisting of a wagon sheet on a pole attached to the carriage. When the breeze failed or the wind was contrary, William Whitelaw and his horse brought the train to the station.”

One picture taken in 1898 showed a railway coach, with sail hoisted, approaching Ardler on the Newtyle to Coupar Angus line. On the track behind the train is the “driver” on horseback, ready with his mount to come into action. In these days a single coach made up the train.

Today the railway continues to make appearances in contemporary documents, such as the Dundee Royal Infirmary Site Planning Brief. In the description of the site, there is noted that “there is a clear change in level between the site of the original building and the Gilroy/Caird/Dalgleish/Loftus wings to the north. This is marked by a series of retaining walls. The site falls sharply to the south boundary from the parterre. To the east the former Burns Unit, Pharmacy and Maternity Wings mark the change in level between Clarence House and the east site. It is through these buildings that the route of the former Dundee and Newtyle railway line runs.”

The railway company was formed in 1826 and in the following year tenders were invited for contractual engineering works. This was the first railway to be built in the north of Scotland. It was planned as a link between the manufacturing city of Dundee and the fertile valley of Strathmore. However it terminated at Newtyle which, at that time, was little more than a mill and a few houses, rather than Forfar or another of the larger Strathmore towns.

The line was built with a 4 feet 6½ inches gauge – there being no accepted standard gauge at that time. It had several unusual features. Rather than going round them, Charles Landale, the engineer, decided on a policy of ‘up and over’ for the Sidlaws – a range of hills – and this resulted in three inclines, at Law (1:10), Balbeuchly (1:25) and Hatton (1:13). The inclines were worked by stationary steam engines. Initially the coaches and wagons were pulled by horses over the intervening level stretches of line. Later two steam locomotives were used although horses provided the back-up when the locomotives broke down.

In its own way the railway was one of the most important early lines in Scotland, opening to traffic on 16th December 1831. It was the first not to rely on a coalfield for the bulk of its traffic, being built to connect the farming areas to the north of the Sidlaws to the harbour in Dundee, carrying general traffic in both directions. The railway was leased to the Dundee & Perth Railway in 1846 and became part of the giant Caledonian system in 1865. Standard gauge was adopted in 1849 and during the 1860s deviation lines were opened to avoid the three inclines, which then fell into disuse.

Photo: J F McEwan

The Law incline ran parallel and to the west of Constitution Street, through the grounds of the Royal Infirmary. The following details are taken from the Account of the Dundee and Newtyle Railway in The Quarterly Journal of Agriculture, Volume IV No XIX, 1833.

“The depot at Dundee is 84 feet above the low-water mark at spring tides in the harbour. The first inclined plane, then, rises from the depot in the Ward to the east side of the Law, 244 feet perpendicular height, along an inclination of 760 yards, at the rate of 1 in 10; then the tunnel is passed through in 400 yards.”

“The waggons and carriages are drawn up and let down the incline by a rope three inches in diameter. The rope passes over metal pulleys and cylinders set about 20 feet apart. It is wound round a large drum of 12 feet in diameter, which is under the command of the engineer by a powerful drag. The inclined plane has a siding upon it. The [stationary] engine [at the entrance to the tunnel] works a double rope, and as this has the steepest inclination of the three, the ascent of waggons at the same time moderates the speed of the descending weight. At the plane where the waggons pass on this incline, the rope is of course bent out of the straight line, and is kept in that position by a sheave of metal of a conical shape, revolving on its longitudinal axis.”

“The [stationary] engine…is a high-pressure one of 20 horse power, made by Messrs Maudesly & Co London. A telegraphic board is placed at the bottom of each inclined plane, to announce to the engineer at the engine that the waggons or carriages are ready to be hauled up; and in thick weather a large bell is rung. A lantern could be used at night, but it is thought inexpedient to use the railway after night-fall for the present.”

In James Nasmyth: Engineer, an autobiography, there is a description of the first adventure by train of an old woman from Newtyle to Dundee. “The woman was on her way down hill, with a basket of eggs by her side. Suddenly the rope broke and the train dashed into the Dundee Station, scattering the carriages, and throwing out the old woman and her basket of broken eggs. A porter ran to her help, when, gathering herself together, she exclaimed, “Odd sake, sirs, d’ye aye whummil (whummil: to turn upside down) us oot this way?” She thought it was only the ordinary way of delivering railway passengers.”

Photo: Elliott Simpson

The tunnel through the Law was completed in 1829. Its construction was also described in The Quarterly Journal of Agriculture. “The greatest difficulty occurred in cutting the tunnel through the eastern acclivity of the Law of Dundee. The greatest portion of this hill composed of greenstone and greenstone porphyry, a stone well adapted for the paving of streets in towns. It was reasonably expected, that the sale of the larger blocks of this rock for paving stone, and the smaller for broken stones for roads, would have realised as much cash as would have paid the expense of mining the tunnel, while the rock itself would have formed a natural archway. But, as Burns truly says, “the best laid schemes of men and mice aft gang agley.” After penetrating a short distance at both ends of the tunnel, it was unfortunately discovered that the line of it had accidentally been fixed up from below with a soft steatitic rock, in a highly disintegrated state, quite unable to withstand the process of mining. Under these unfavourable circumstances the tunnel had to be lined up on both sides with walls, and arched over with freestone and mortar. Thus, instead of realising the reasonable anticipations of a saving of expense, the formation of the tunnel incurred an extraordinary outlay.”

Photo: Elliott Simpson

At the outbreak of World War II, the emergency Committee asked the LMS Railway Company for the use of the Law tunnel as a shelter. According to This Dangerous Menace: Dundee and the River Tay at War, 1939 to 1945 by Andrew Jeffrey, “This was agreed to at a rent of one pound per annum, provided the Corporation undertook to return the tunnel to the condition in which they found it. In February 1941 Ellen Wilkins, Minister at the Home Office, noted that the Law tunnel had no amenities and described it as one of the wettest shelters she had ever seen. In addition it was very cold and was never a success. Plans for a grid square of tunnels westward of the present tunnel with exits to Kinghorn Road were quietly dropped.”

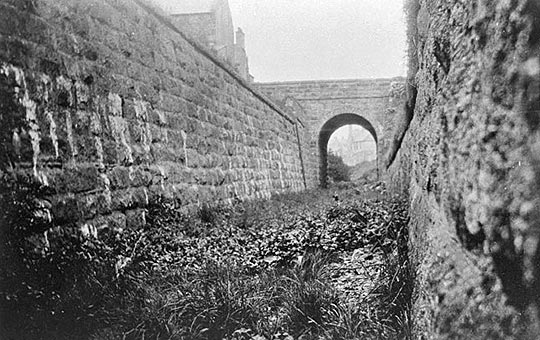

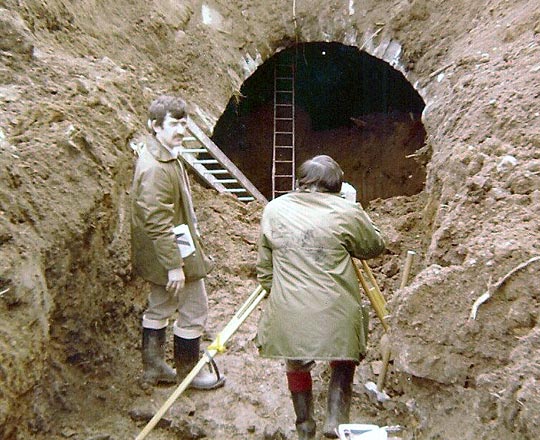

The south entrance was still open in the 1960s, tucked in below a wall at the top of Upper Constitution Street. It then ran under some allotments and between houses on the north side of Law Crescent. It was in some nearby allotments that my friend and I found the north end of the tunnel. It had been covered with rubble but over the years the ground level had lowered, revealing the top of the arch – and that gap was wide enough for us to get inside. A few minutes later we were at the south end, congratulating ourselves that we had achieved what his mother had not.

Photo: Elliott Simpson

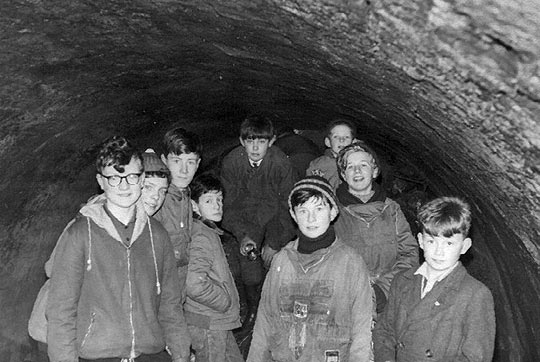

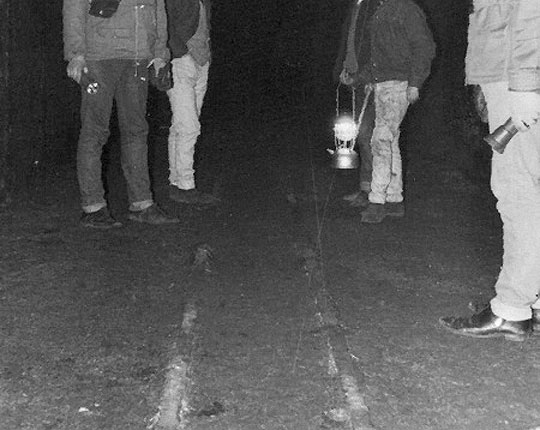

A few weeks later, we returned in the evening with a group of kids from the Broughty Ferry Crusader Bible Class, where I was a leader. As we were crawling into the tunnel, three local lads came to see what we were doing. Rather than leaving them outside to report who-knows-what to who-knows-who, we took them – very willingly – along with us.

The mound of rubbish inside quickly descended to the original tunnel floor level. Half way through there was a blast wall and on the north-facing side were the words “EMERGENCY EXIT”, so one assumes that the north end of the tunnel must have been open in the 1940s when it was used as an air raid shelter. Rails were still in place, said to have been laid for a narrow gauge track way used by a company which grew mushrooms in the tunnel. Hanging from the masonry lining were hundreds of stalactites.

Photo: Elliott Simpson

The track through the tunnel and the north side of Dundee ran more or less level for 4¾ miles until it reached the second incline at Rose Mill in the Sidlaws. In 1833 The Journal of Agriculture stated that “The level spaces are so constructed that they each form two straight lines, with the view that should it afterwards be thought expedient to adopt stationary engines instead of horses, they could be erected at the meeting of the straight lines for the dragging of waggons along the levels.”

It is probably for this reason that there are several buildings which now appear to be out of align with the road system, because they were aligned to the track. One of these was the station master’s house in the grounds of Kings Cross Hospital on Clepington Road; another was Trendell Simpson, the printers in Lintrathen Street. This latter building was bought by my father in 1948 and the business has been in the family ever since.

Photo: Elliott Simpson

In Priestley’s Navigable Rivers and Canals, the length of the first level section is given as nearly 4¾ miles. At the end of this was the second incline which took the line up a height of 200 feet over a distance of 1,690 yards. This was the Balbeuchly incline. It had a gradient of 1:25 and was named after the farm at the summit. The bottom end of the incline was at Rosemill. In 1966 there were two intact bridges, and another without its spans, which crossed the Dighty Water – the local stream – and a mill lade at Rosemill. The centre bridge led to the deviation line which was opened in the 1860s.

The Journal of Agriculture states that “a difficulty occurred at the forming of the inclined plane at Balbeuchly. Here the great hollow in the fields had to be filled up to the height of about 40 feet above the ground; and this great embankment was formed of travelled rubbish. To obtain materials for filling up as near to the spot as possible, a portion of the ground at the top of this inclined plane was removed, which had the effect of keeping down the height of the level over the bog of Auchterhouse, and affording space for the engine-house.”

Priestley’s Navigable Rivers and Canals gives the length of the second level section as being four miles and a furlong, with a rise of only 3 feet 9 inches. The track bed from the top of the Balbeuchly incline can be seen as a wooded embankment crossing the fields and meeting the end of the second deviation just to the north of Auchterhouse Station.

The line from Auchterhouse north runs across a former marshy area. In the Journal of Agriculture it is said that “One difficulty was the passing over the bog of Auchterhouse, the moss in which has always been of so soft a consistency that no cattle could walk across it. The passage over it was accomplished by digging the moss to a considerable extent on each side of the railway, and throwing it up in the shape of an embankment, upon which the railway is placed above the ordinary level of the moss. The large ditch thus formed on each side of the railway not only dried the moss upon which the railway rests, but it has drained the bog for a considerable distance on each side; so that corn and grass may be seen growing where they never did before. The slopes of this mossy embankment are planted with trees appropriate to their situation, such as willows, poplars, spruces, and alders.”

The 1:13 Hatton incline at the northern extreme of the line, was the last of the three stationary engine-worked inclines to close, when it was superseded by a deviation line in August 1868.

The station at Newtyle was the terminus of the Dundee & Newtyle Railway. In 1833 the line had 31,000 passengers, a number which had risen to 61,000 by 1839. In a very real way, the railway brought Newtyle into being.

Although it was always intended that the line should be steam powered, it was recognised that horses would provide the pulling power in the early stages. In the Journal of Agriculture, it is pointed out that, “although at the time when this railway was constructing, the Stockton and Darlington railway was the only one which was in existence on the same principle, the workmanship of the Dundee and Newtyle one is very superior to any one even now in use. The using of large stone-sleepers to support the rails, the placing the rails high above the horse foot-track out of the reach of mud, and the peculiar mode in which the rails are keyed into the iron chairs, which prevents their starting up, are peculiarities and superior modes of workmanship on railways which were first exhibited here. Indeed, on the whole, this railway is a piece of work, both as to the direction of the line and the style of the workmanship, that reflects the greatest credit on the professional talents of the engineer.”

Some idea is also given of the rolling stock. “Carriages for the conveyance of passengers are made of various forms, but they all move on the same kind of wheels as common waggons. There are close-bodied coaches, open vehicles with awnings, parcel waggons, and covered carts with benches, for poor people on market days. One horse trots with a number of them together at the rate of eight miles in the hour. Once we were conveyed along with 64 passengers by one horse at that rate. The motion in riding is not so smooth nor so noiseless as one might imagine; but this may be owing to the rails being placed on hard stone-sleepers, for on those parts where the wooden sleepers have not yet been removed, the motion is much smoother.”

“The service waggons are made of wood or plate-iron, we believe the later are preferred. They discharge their contents through the bottom. They are placed on a frame-work, supported on four wheels of cast-metal, 35 inches in diameter, and they weigh about one ton each, and are intended to carry a burden not exceeding two tons. They are fastened together by a strong iron bolt passing through eyes in bars of iron, and at the inclined places they have precautionary safety chains attached to them. They have each, besides, a drag, like a hammer-headed lever, which operates on the tires of the fore and hind wheels at the same time. Four waggons loaded, of a gross weight of 12 tons, is one horse draught; and he can walk away with this at the rate of at least three miles in the hour.”

In the Journal of Agriculture there is a series of calculations on the weight of crops, etc. which might be expected to be transported out of the Vale of Strathmore. There is also the following section which estimated the costs of running steam locomotives on the lines, rather than using horses.

“The level part of the railway has hitherto been served by horse power; and at the outset of such a work as this, when the business upon it had to be acquired, and no certain anticipations of great immediate traffic could be depended on, it was highly expedient not incur the expense of locomotive steam-engines. As the strength of the rails is only 28lb per yard, it is very questionable whether that strength could have borne the locomotive engines which were first used, especially such as those used on the Liverpool and Manchester railway, which weigh from 6 to 8 tons each, and are borne on a rail of the strength of 36lb per yard. Under these circumstances, Mr Nicholas Wood, the eminent colliery surveyor at Kilingworth, recommended the weight of carriages with the goods not to exceed 3 tons each, and that they should be propelled by horse-power. In this manner the business of the railway has gone on hitherto very smoothly, one horse dragging along four loaded waggons of 3 tons each, at the rate of perhaps more than three miles per hour. The rate of freight is 4d per mile per ton.”

“Now, however, that locomotive engines are improved in their construction, and the economy in their consumption of fuel seems to be brought down to the minimum point, it is worthy of immediate consideration, whether they should not be employed on this railway in preference to horses. The two level plains would require an engine each. The light engines of Mr Gurney’s construction could work upon them with great advantage.”

“But as example is better than precept at all times, and particularly in matters of experiment, we shall state what one of Mr Gurney’s locomotive engines performs on a railroad in Wales. Mr Crawshay of the Cyfarthfa iron-works in Glamorganshire, South Wales, states in a letter to Sir Charles Dance in February 1832, that the engine which he got from Mr Gurney for his railway at Hirwain, did not weigh above 35cwt, including water and fuel, and every other thing in a working state; that this engine conveyed, between 1 January 1831 and 1 January 1832, of coal, ironstone and iron, from 20 to 30 tons at a time as suited convenience, exclusive of the weight of the carriages on which they were drawn, 42,300 tons a distance of 2½ miles; that during that time the engine was half idle, though it was kept “working idle”, as he expresses it, in order to keep the boiler full; that the quantity of coals consumed in that time was 299 tons at 3s per ton, £44,17s; that the wages of the engineer was £52, and those of a boy £15,12s; and that with oil and other trifling matters the whole expense amounted to £112,9s, or less than one farthing per ton per mile for the goods conveyed; and that from his long experience of horse power on railroads, he conceives that steam power is cheaper than it, in the proportion of 1 to 20 or 30. He concludes by earnestly recommending the cheaper power of steam, wherever practicable, for that of horses, and says there are “many other valuable considerations in favour of that of steam, known only to those who have large and expensive stable.”

Photo: Elliott Simpson

In 1810, James and Charles Carmichael founded the Dundee company which produced the first locomotives for the Dundee and Newtyle Railway in 1833 – these were, in fact, the first locomotives made in Scotland. It is said that they were the first in the UK to have bogies. Prior to that, the company’s main activities were marine work, weighbridges and turbines.

The first locomotive, No.1 and named Earl of Airlie, was delivered on 20 September and No. 2, Lord Wharncliffe, on 25 September 1833. These were the names of two of the local land owners who were principal share holders in the company. They were both 0-2-4s. The cylinders were placed on each side of the boiler; the crossheads above the cylinders were connected to large bell cranks, the longer arms of which were coupled to the connecting rods fastened to outside cranks on the leading 5 feet 4 inches diameter wheels. All wheels had laminated springs above the frames. The steam admission was by means of a valve on the boiler barrel, operated from the footplate by a handle and shaft. The feed check valve was on the side of the raised firebox.

Early in 1834 a third locomotive was built by Stirling of Dundee to the same general design as the first two, and named Trotter. A fourth, called John Bull, was obtained in 1836 from Robert Stephenson & Co of Newcastle. Unlike the other three, this had the 0-4-0 wheel configuration.

An extension of the railway onwards to Glamis was authorised in 1835, opening to goods in 1837 and to passengers in 1838. It was built by an independent company, the Newtyle & Glammiss Railway, the company using the old spelling of the village name. Around the same period, the separate Newtyle & Coupar Angus Railway opened. Eventually both of these railways were taken over by the Scottish Midland Junction Railway and used in part for the new route between Perth and Forfar, opened in 1848.

Passenger trains operated on the Dundee & Newtyle from its earliest years. All trains were operated according to parliamentary regulations introduced in 1844. In February 1862, there was a service of three trains in the Dundee-Newtyle direction and four the other way, with a fifth on Fridays. Some trains were mixed, for both goods and passengers. Connections onwards from Newtyle to Coupar Angus, Blairgowrie, Alyth, Glamis, Kirriemuir and Forfar were available; also a service of short workings between Dundee and Lochee. By this date both the Law and Balbeuchly inclines were closed but trains would have required to use the stationary engine-worked incline between Hatton and Newtyle until 1868.

Photo: Elliott Simpson

Closure of the railway came in stages, with the section between Newtyle and Auchterhouse the first to succumb in 1958. The rest survived into the 1960s but the history of the Dundee & Newtyle Railway ended on 6 November 1967 when the Law incline deviation line closed between Ninewells Junction and Maryfields Goods station. The north end of the Law tunnel was lost again when housing was built on the allotments where I had found it; the southern entrance was bricked up and buried in 1982. But however much it gets hidden, the tunnel will always remain in my memory thanks to the excitement of that underground adventure.

More Information

| Elliott Simpson | Elliott’s personal website, with more railway reminiscences |

| Theatre Organs | The route of the Law incline and tunnel today |

| Retro Dundee | Photo of another children’s adventure about to begin |

| Dundee Community Podcast | Wider view of the southern entrance |