Kelvingrove Tunnel

Kelvingrove Tunnel

June 1888 brought the passing of a Parliamentary Act for the construction of a predominantly underground line through the centre of Glasgow, appropriately entitled the Glasgow Central Railway. It was aligned north-west to south-east, running for about seven miles from Maryhill to Rutherglen. The company was absorbed into the Caledonian Railway’s empire a year later. The ceremonial cutting of the first sod, on 10th June 1890, was undertaken by Master J B Montgomerie Fleming, son of a local bigwig.

For construction purposes, the line was divided into four contracts. The third of these covered the section between Stobcross Street and the River Kelvin, a distance of 2,323 yards. Successful in tendering for the work, at a cost of about £250,000, was James Young & Co. Responsible for the engineering on behalf of the Caledonian was Charles Forman of Forman & McCall; the resident engineer was Donald Matheson.

Having briefly enjoyed daylight on leaving the short tunnel under St Vincent Crescent, trains were again plunged into darkness as they travelled northwards under Kelvingrove Street and the park beyond it for around 942 yards. They emerged in the shadow of a bridge carrying Gibson Street over the railway and river, before curving westwards to reach Kelvinbridge Station.

The tunnel demanded a number of construction methods. At its south end, “core tunnelling” was used to get under buildings on the south side of Argyle Street. This involved short sections of heading being driven at the crown of the intended tunnel, 4 feet square, from which excavations were progressed around the profile, down to invert level. These voids were then filled with concrete and brickwork, allowing the ground beneath to be safely removed. It was thus possible to construct this part of the tunnel in lengths of 4 feet, without affecting the buildings just inches above.

The next 270 yards used a “concrete safety arch” as a means of minimising disruption as it passed 35 feet under Kelvingrove Street. The roadway was opened up on one side and, to protect adjacent properties from subsidence, timber piles were then driven to a depth 4 feet below formation level. This was accomplished by a piling machine with a 2½-ton ram which could simultaneously drive three piles 3 feet in 1½ hours. In constructing this section of tunnel and another at Stobcross, 5,500 piles were needed – each 28 feet long and 12 inches square – which would have extended for 30 miles if placed end-to-end.

The exposed ground below the removed roadway was shaped to form a half-arch. From the low point of this arch, a trench was then sunk down to track level – alongside the piles – within which the tunnel’s sidewalls could be built. Thereafter, concrete was poured into the excavation, creating a saddle 2 feet 3 inches thick at the crown and more than 6 feet at the haunches. The roadway was then reinstated before the same process was carried out at the other side, resulting in a concrete arch being formed the full width of the tunnel. The material beneath it could then be excavated from shafts along the street and the lining constructed.

Hampering activity was a sewer running up the middle of Kelvingrove Street which had to be transferred temporarily into a wooden trough. A new brick sewer was built to replace it as the work moved forward.

On 2nd September 1892, with this portion of the tunnel almost complete, the arch collapsed beneath the junction of Kelvingrove Street and Royal Terrace, resulting at a 10 feet square hole in the lining; at street level, it was 30 feet square. Nobody was injured below ground, the navvies having received enough warning to make good their escape; on the surface, a horse and cart had passed over just seconds before the road gave way. The cause of the accident was thought to be heavy rain percolating through the ground and washing out the mortar.

Beyond Kelvingrove Street, the line passed under West End Park, the gradient easing from 1:100 to 1:260. It had originally been intended to have a station here and, to that end, hoardings were put up, behind which a large box was excavated to accommodate it – 100 yards long, 44 feet wide and 24 feet high. This would have been spanned by steel girders supported by concrete sidewalls, dressed in white glazed brick. But Glasgow Corporation rejected the idea with the station already well advanced, concerns being raised about the impact of a working class influx on the delicate middle classes thereabouts. Had this decision been made sooner, conventional – and much cheaper – tunnelling methods would have been adopted. As it was, a brick arch was instead installed, the box backfilled and the parkland restored to its previous state.

To the north, the railway passed under the hillier part of the park in a bored tunnel of 465 yards, reaching 90 feet below ground level at its deepest point. A summit was encountered close to the midpoint, climbing northwards at 1:100 before falling towards the exit at 1:850. The alignment here curved first to the east before a short westerly curve took over through a final 50-yard cut-and-cover section adjoining the portal.

The excavation work here benefited from two shafts. The southernmost was rectangular in plan, the full width of the tunnel, 45 feet deep and lined in dressed stone above arch level. The adjacent lengths of lining are 10 bricks thick. On completion, this shaft was capped at the top with a vaulted brick roof; there is no sign of the other. The mining here was hard going, but the arisings provided a good source of freestone, useful for the portals, bridge piers and abutments further along the line. The self-supporting rock meant that a lining just 18 inches thick was needed through most of this section.

The railway was inspected for the Board of Trade by Colonel Addison in July 1896 and fully opened on 10th August. To ensure the route remained well ventilated, seven specially constructed condensing engines plyed their trade on the line whilst a substantial fan was installed near Wellington Court.

The line retained its operational status until 5th October 1964.

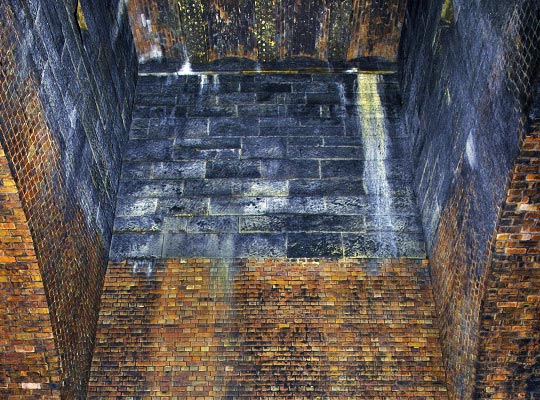

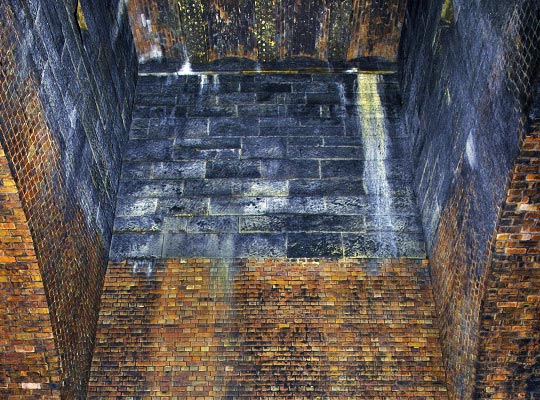

The tunnel today is in generally fair condition, although considerable water ingress results in the solum being wet, with extensive calcite deposits on the lining; there are also large localised accumulations of ochre. In 1994, floodwaters from the River Kelvin entered the tunnel and were carried as far as Central Station (Low Level). Perhaps as a consequence, the p-way drain failed and the southern part of the tunnel – together with its approaches – was affected by deep pooling. Remedial work was carried out in 2012 during which stone was tipped, raising the floor level by around 5 feet.

For much of its length, the tunnel has a rounded profile. But in the cut-and-cover section under Kelvingrove Street, the sidewalls are vertical and, for the most part, the brick arch springs off benches in the concrete safety arch at a height of 6-8 feet.

Refuges are plentiful and deep. The lining still hosts a collection of old railway furniture including several timber boxes and fixings, together with rows of cable hangers. Under Sauchiehall Street (formerly known as Sandyford Street where it crosses the tunnel line), a cast iron sign is affixed to the wall. Also here, the lining is cut through by an iron trough carrying a sewer.