Hose (Clawson) Tunnel

Hose (Clawson) Tunnel

Proposal and counter-proposal from the Great Northern and Midland railways – some of which fell victim to opposition by local landowners – eventually resulted in the GN securing Parliamentary approval for a line from Newark to Melton Mowbray in 1872. The following year, a further section was authorised, extending the route southwards to meet the Rugby-Luffenham line, a product of the London & North Western. The upshot of this was that the GN and L&NW came together in the construction of a 34-mile north-south Joint Line between Welham and Bottesford, together with the associated connecting spurs and link lines.

Heading north from Melton, the section to Saxondale Junction on the Nottingham-Grantham line opened for business on 1st September 1879. Stathern to Newark through Bottesford, and Melton to Welham/Drayton junctions became operational on 15th December.

In places, the line demanded substantial structures, including viaducts at John O’Gaunt and East Norton. Responsible for their engineering was John Fraser, who was the Great Northern’s chief engineer before setting up in partnership with his son in the late 1870s.

Two tunnels also had to be driven, the longer of which – at 834 yards – was located just to the south of Long Clawson Station, and officially went under the name of Hose; Clawson provided its pseudonym. From the north, the line approached via a curve to the east of 40 chains radius which extended a short distance into the tunnel. Thereafter it followed a straight course before another curve of an identical radius was introduced just inside its southern entrance. The gradient throughout was 1:120, climbing towards Melton.

Benton & Woodiwiss – regular servants of the Great Northern Railway – were appointed as construction conctractors. The heading, measuring 10 feet high and 9 feet wide, was driven from two shafts, the more northerly being the deepest at 106 feet. The other measured 86 feet. Both were sealed and backfilled once construction work was completed. Two other shafts were sunk just clear of the proposed entrances to expediate work on the approach cuttings, although it appears that the north portal was eventually erected about 40 yards north of the shaft at that end.

On Saturday 14th October 1876, eight men were working at the Bottesford face of the heading being pushed forwards from No.2 shaft, about 120 yards from its base. Progress was being made through hard clay at a rate of about 1 yard per day, with blasting operations usually taking place twice during each of the two daily shifts.

About half-past nine in the evening, John Sismey, John Foster and Samuel Longman were engaged in the top heading, with their work illuminated by three candles. As he attempted to charge a hole with gunpowder, Longman – called “Scandalous” by his fellow navvies – managed to strike his container, known as a tot, against some projecting earth, resulting in the gunpowder being scattered, coming into contact with one of the candles and igniting. This caused the remaining gunpowder – about 8lb of it stored in a can – to explode, as well as that already introduced into another hole. All three sustained serious critical; Foster and Sismey later lost their fight for life. Five other men suffered burns, including the foreman who was upwards of 20 yards away.

On 26th June 1878, a young brakesman named James Clark was killed when he was run over by a waggon, 200 yards into the tunnel. He left a widow and three children.

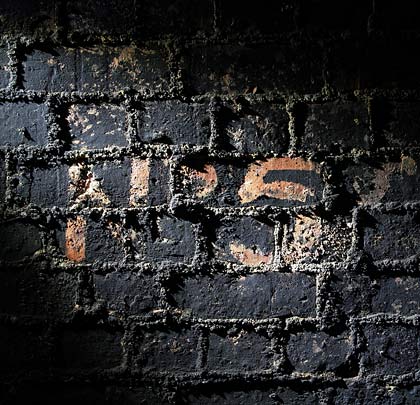

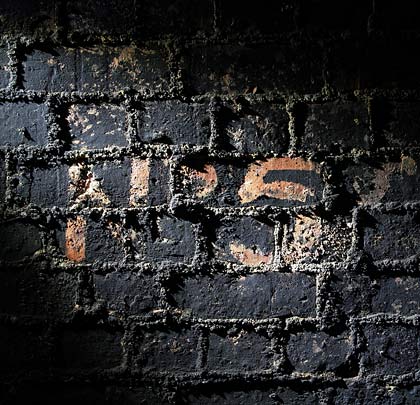

The tunnel is lined throughout in red brick although short sections of masonry sidewall are apparent – presumably later repairs. Two of these face each other near the tunnel’s centre, across an open catchpit. Another, inserted in the east wall close to the northern entrance, is badly spalled. Deep refuges are provided at both sides.

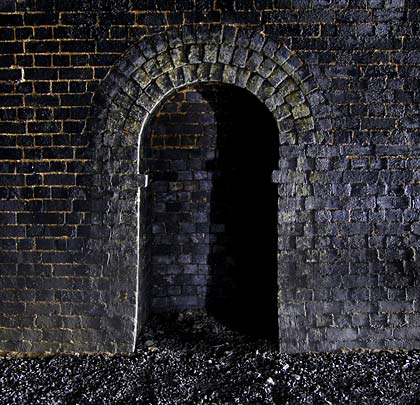

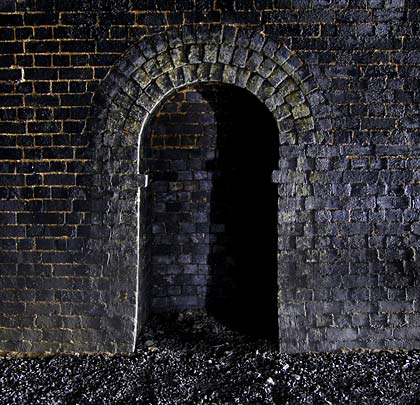

The north portal is hugely impressive, looking like it was built yesterday. It exhibits seven rings of brick and a headwall in blue brindles. The wing walls, buttresses, parapet, string course and copings are all stone, with the former aligned parallel with the trackbed. At the south end, masonry was used for the string course and copings; the rest is engineering brick. Here, the wing walls are set at right angles to the railway.

A mechanical gong was fixed to the Up sidewall, 34 yards from the northern entrance. This was used for signalling trains during shunting operations at Long Clawson. A telephone to the signal box there – with wires running through the tunnel – was located in front of the watchman’s hut on the Down side, 120 yards beyond the south portal.

Regular passenger services along the route were never well patronised and ceased on 7th December 1953. Goods traffic was more successful, continuing to encounter Hose Tunnel until the section through it was closed on 7th September 1964. A meandering line from Wycombe Junction to Asfordby Colliery – which passed over the southern half of the tunnel – was jettisoned in 1963.

Today the structure remains in generally good condition and is clutter-free except for a collection of chicken cages stored at the northern end.

February 2013

February 2013