The story of Haddon Tunnel: Hidden Haddon: its rise and fall

The story of Haddon Tunnel: Hidden Haddon: its rise and fall

If the procrastination over High Speed 2 ever gives way to construction, the line will navigate the delicate Chiltern Hills via a series of tunnels – some bored, some ‘green’. The latter comprise open-ended concrete boxes, sunk into the landscape, above which the ground is restored to something resembling its original state. It’s a modern term but a well-established principle. When the Midland Railway pushed its Buxton branch through the Peak District in the 1860s, it was obliged to excavate the 1,058-yard Haddon Tunnel so as not to blight the gentry’s views from the adjacent hall. Opened 150 years ago this month, the structure has lain silent since closure claimed it in 1968.

Those who engineer the green tunnels of HS2 will enjoy many advantages over the workforce at Haddon: laser-driven surveying equipment, high-capacity cranes and earthmovers, welfare facilities, foul weather gear, and not forgetting the restraining harness of health and safety. However much of a national embarrassment this has become in the 21st century through stifling regulation and risk aversion, better that than the havoc that was gruesomely wreaked in the 19th century at many railway construction sites.

On the defensive

Inspired by notorious mogul George Hudson, 1845 brought the depositing of Parliamentary plans for an ambitious new railway connecting Ambergate – north of Derby on today’s Midland Main Line – with Manchester. Guiding the heavy engineering was George Stephenson whose initial proposals identified a route up the Wye Valley until the Duke of Rutland’s opposition prompted a diversion through the Chatsworth Estate, owned by the supportive Duke of Devonshire. Alive to the commercial impact of being bypassed by the railway, the persuasive townsfolk of Bakewell managed to change the Duke of Rutland’s mind and he contrived to block the plans in the House of Lords. An alternative alignment was put forward, also through the Chatsworth Estate, with branches serving Buxton and Bakewell. But the delay proved critical. By the time Royal Assent was granted, the unsustainable financial drain of railway mania had caused the flow of money into such schemes to dry up. The line was progressed as far as Rowsley, opening in 1849, but the land beyond remained untouched for more than a decade.

The Midland Railway’s rivalry with the London & North Western manifested itself in a chess-like game whereby the former’s goal of securing a slice of Manchester’s lucrative rail market was thwarted by the latter’s defensive manoeuvring. With no hope of collaboration, the Midland was forced to push forward with an independent route, the first section of which involved a 15-mile extension of the Rowsley line into Buxton, authorised in May 1860.

Towards its western end, the River Wye meanders through its spectacular limestone gorge which was overcome by eight tunnels and a collection of assorted viaducts. Whilst the eastern section presented fewer obstacles, the terms set down by the Duke of Rutland for accommodation through his estate gave rise to the line’s most substantial engineering exploit, that of Haddon Tunnel which would bury the railway behind the hall from which its name was taken.

Best laid plans

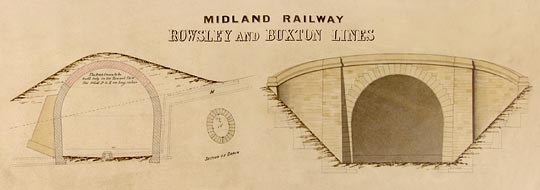

Initial drawings for the structure survive in the Midland Railway Study Centre, with three signatories. Most notable is that of William Henry Barlow, installed as the Midland’s first Chief Engineer in 1844. By this time he had left to establish a private London practice, albeit retained by his former employer following Stephenson’s retirement. Barlow was later celebrated for the outstanding St Pancras train shed and his design for the replacement Tay Bridge. George Thomson, fulfilling the role of contractor, and his brother Peter also appended their names. This was a prolific and highly respected pair, credited with building a number of lines in South Wales, the North West and Yorkshire.

Courtesy of Midland Railway Study Centre

On paper, Haddon was envisaged as two tunnels, separated by a short cutting. The most southerly would extend for 120 yards, sitting on a ledge cut in the gently-graded hillside and covered to conceal its segmental arch to a depth of just a few inches. Beyond this, a longer structure of 900 yards – punctured by two ventilation shafts – would comprise cut-and-cover sections either side of a bored portion. Towards the southern end, a series of drains were planned to channel ground water beneath the tracks where the land fell to below the height of the arch. Even at its deepest point, the crown was barely 30 feet below the surface.

But anyone visiting the tunnel today would struggle to recognise it from that description. Two shafts became five; the cutting disappeared; substantial changes in section are met; an open box near its centre brings 11 yards of daylight. Engineering contracts generally demand that work is carried out in accordance with the plans and specifications unless unforeseen problems are encountered. Trouble is, with activities below ground, virtually everything is unforeseen. So it should come as no surprise that the design evolved in response to prevailing circumstances. And clues to what they were have been left for us by civil engineer John S Allen.

The earth moves

On 12th December 1861, Allen presented a paper on the tunnel’s construction – which by then was just a month from being finished – to the Civil & Mechanical Engineers’ Society. This records that the stratum traversed throughout was shale overlying limestone, with a varying thickness of clay above it. During the course of the work, movement of the clay caused several extensive slips to occur, whilst ground pressure was sufficient to break 18-inch timber crown bars.

As built, the structure rises towards Bakewell on a gradient of 1:102 and comprises three sections: from the south portal, a covered way of around 490 yards, then a 350-yard tunnel, followed by another cut-and-cover section of 220 yards incorporating a curve to the east of 40 chains radius. Ground was broken on 10th September 1860 with the sinking of a shaft close to the main tunnel’s midpoint, from which a heading was driven to meet those already advancing from its ends. April 1861 saw work get underway at two points within the heading to excavate the tunnel to size, allowing four faces to be worked simultaneously. Progress was made in lengths of 12 feet, each requiring 12 crown bars, two miners’ sills and about 30 props of varying dimensions, as well as rakers and poling boards.

Allen described the production line process: “The masons follow and build in the side walls, which are of sandstone grit, excellent in quality. This stone is found in great abundance in neighbouring quarries. The walls are built in block-in-course masonry – one header and two stretchers. These courses are backed up with rubble work, in sandstone or limestone. The thickness of the work is on average 2 feet 3 inches.”

“A profile is erected at the end of each length to guide the masons. The bricklayers follow as soon as the centres are set, which are of great strength and excellent in design. The arch, which is a semicircle, consists of 5 or 6 rings of bricks, as the ground may require it. These bricks are made on the contractor’s premises; good clay fit for the purpose being found adjoining the works.”

Ground force

Beyond the tunnelled portion, the covered ways took shape. Having opened the ground to the requisite depth, side walls and arching was inserted and the excavation then backfilled. “There are several sections of arch used”, declares Allen. “The principal one is that of a low stone arch, having a rise of 6 feet from the springing line. A semicircular arch of stone is also employed when the cutting is deep. The thickness of the arch is in all cases 2 feet.”

Towards its southern end, it is possible to walk alongside the tunnel at track level, such is the shallowness of the fill and gradient of the slope. As a consequence, the ground could not sufficiently counteract the thrust of the arch, prompting the introduction of “strong counterparts”, in the form of buttresses, to support the west wall, as well as increasing its thickness. Several buttresses are now exposed, the land having slipped off them over the years.

Allen concludes that “The works are of an interesting and instructive character, and have been carried on with very slight interruption night and day.” In just 16 months, Haddon Tunnel had been buried seamlessly beneath the Duke of Rutland’s estate. Whilst Allen was right to celebrate it as an engineering success, one unmentioned failure – the cause of that “very slight interruption” – had a human impact that should not be overlooked.

A nomadic existence

Alfred Plank was a lad of 15. On 7th April 1861, the national census records him as living in one of five ‘sod huts’ erected for the navvies at Great Rowsley, about a mile from the tunnel. Ten souls inhabited it, with Alfred’s father William head of the household. His wife Sarah and five of their eight children were joined by three boarders, also employed on the railway.

It seems likely that the family followed the contractor around the country as work arose. The youngsters were born in towns across South Wales; by 1851, home was north of Newark alongside the East Coast Main Line, then being built by the Great Northern. Now in Derbyshire, Alfred and his 13-year-old brother Charles were both wage earners, working on the Buxton line as horse drivers.

Living conditions would have been basic but comfortable, unlike those at work. More than 250,000 navvies served the railways when construction was at its peak in the mid-1800s; a good one could earn three times that of a farm labourer. Many were skilled – miners, masons, riveters, bricklayers, carpenters. Their welfare however was not a corporate priority.

Centres of excellence?

It’s fair to presume that Tuesday 2nd July 1861 was much like any other. Within the northern section of covered way, a 36-foot length of arch was waiting to be keyed with three courses of stonework. The centring that supported it comprised eight ribs, each with props at both ends and another in the middle. These stood on blocking stones of up to two feet square. Three rakers steadied the structure. The same centres had been deployed in the construction of four other lengths and were deemed fit for purpose again, their assembly overseen by carpenter Edward Sykes who inspected them twice daily.

Seventeen men were busy hereabouts. During the early part of the afternoon, two or three loads of stone arrived, pushed up a wagonway that passed between the props. Each wagon was opened at its end and the contents tipped into the metals. The blocks, some measuring 3 feet in length and weighing 3-5cwt, were then manoeuvred within reach of a derrick, ready for hoisting up to the masons. This was located at the north end of the arch, fastened to the centres by a pair of iron dogs. Operating it was Alfred Plank, with motive power for chain-pulling provided by his horse.

Having just been emptied, six men pushed a wagon away from underneath the stonework. Up top, some of the masons paused for a breather whilst labourers adjusted the wooden boards on which the materials were wheeled, leaving 36-year-old George Buckley, Jacob Rowland, George Twyford and Frederick Bacon still on the centring. Then all hell broke loose. According to Bacon, “I dropped down just as if I had been suspended in the air by a cord, and the cord had been cut. There was not the slightest warning, not the least imaginable.”

Photo: The Rowsley Association

The arch had gone. All hands immediately began clawing at the debris. Messengers were sent to Bakewell for medical assistance; surgeons Knox and Evans attended. By six o’clock – two hours after the event – the victims had been extricated. Lost were John Millington, aged 40, James Bird, 36, and 21-year-old James Clarke. Two were found side-by-side, horribly crushed. And just a few feet from safety was the boy Plank, lying alongside his horse. A cart carried the bodies to the Royal Oak in Bakewell to await the inquest. Buckley had survived with the loss of both legs, but succumbed in the early hours. A sixth man, Francis Evans, emerged with a broken leg; Twyford also suffered leg injuries.

Whys and wherefores

The affair cast a shadow over the district; the following day, hundreds arrived on site to pay their respects. Thursday saw mourners gather in Rowsley for James Clarke’s funeral; Alfred Plank was buried there on the Sunday.

At the Royal Oak, it fell to Coroner F G Bennett and a jury of 12 gentlemen to seek the accident’s cause, hearing two days of witness testimony. Much attention was paid to the centres, determining their condition and the impact of bolt holes drilled through them. Whilst it was asserted that their strength might have been diminished by as much as 25%, expert opinion concluded that they were still working well within their combined 560-tonne capacity, bearing about 120 tonnes.

It was learned that it had not been general policy to insert a middle prop until George Thomson had insisted upon it about a week earlier, “to make sure”. Edward Sykes revealed that the lone raker at the north end of the centres had been taken away some time before the accident, although this was not unusual. “They were put up to steady the centres and not to support them”, he insisted. A small land slip had occurred, depositing material onto one of the side walls, but the quantity was such that it could in no way account for the collapse.

In the end it was W H Barlow who glued the clues together. “The statements of the witnesses indicate that the [eastern] end of the centres swerved out towards Rowsley, and also that all the centres twisted on their sides, the tie-beams being found towards Rowsley and the upper rib towards Bakewell. The only reasonable mode that occurs to my mind for explaining those appearances is that one or more of the props on the [eastern] extremities of the centres had been knocked away. It is possible that in unloading the stone, if unloaded on that side, or in moving the stone afterwards, the props might have been knocked away… The loss of a single prop…might cause the whole weight, by giving a twisting action to the centre prop, to give way.”

Tragic episodes

Accidental death became an occupational hazard for the navvy – tight margins and inadequate control measures conspiring against him. Early in September 1861, 22-year-old John Bishop, also a horse driver, was knocked down in the tunnel and then run over by wagons. But such events did little to impede progress. The structural work was concluded on 11th January 1862, the Duke’s agent having authorised the retention of five ventilation shafts rather than three as first agreed; by April, only a section of permanent way was missing. The first public train passed through at 7:20am on 1st August, running to a temporary terminus at Hassop, three miles away. Buxton was connected in May 1863.

Even then, misfortune could strike. On Saturday 24th July 1869, a boy named William Cutts left Derby on an excursion train, heading for Matlock where he intended to sell fruit. As his journey neared its end, drunken railway ganger Henry Southgate took 5lb of plums from him, but refused to pay. Threatened with the police, the miscreant attempted to escape feet-first from a window as the train passed through Haddon Tunnel. The boy grabbed him by the hair, shouting “Either leave the plums or money before you go!” Southgate did neither and fell onto the track. The guard, joined by a porter from Bakewell, found his body in the four-foot of the Down line close to the tunnel’s midpoint, minus its head and a leg.

Photo: J R Morten

The early hours of Thursday 5th June 1884 saw more tragedy. Francis Irish, a guard from Kentish Town, described how he heard a loud knocking beneath his van as the 11pm mail train from Liverpool passed through the tunnel at 50mph. He thought that some brickwork had come down. On arrival at Derby, the driver took his hand lamp and examined the locomotive, finding “blood and brains” on the front part of the bogie and a piece of cloth wrapped around the feed pipe. Shortly after 2am, goods inspector Matthew Knott and ganger Watson were despatched to the tunnel where they found the dismembered remains of a “working man” scattered over a distance of several hundred yards.

Test of strength

As the 19th century drew to a close, it became apparent that all was not entirely well with the structure. At No.3 shaft, inspections had detected a movement of 1½ inches at one side of the brick arch. Difficulties were also being experienced with ventilation – smoke was accumulating due to increased traffic levels. In July 1900, the Chief Engineer’s Office in Derby drew up plans to remove both the shaft and 33 feet of arch around it, instead constructing a large open box. Work got underway almost immediately, taking eleven months. Appointed as contractor was Chas Baker & Sons of Bradford.

With earth removed from above the brickwork, “a few stalwart masons” gathered on the morning of Sunday 2nd December, waiting for the start signal that would follow the passage of the 10:38am service from Bakewell. Great difficulty was experienced breaking away the crown but, once gone, the remainder fell with little persuasion. A gang of Midland Railway men cleared the debris, allowing services to resume before midday – passenger trains having incurred no delay at all. Inspector Groves took charge of a pilot engine to regulate movements. A second section of arch was similarly dispatched the following Sunday.

Such an intrusive scheme would not have been undertaken lightly, given its complexity and operational impact. The extent of the works offers some insight into the concerns engineers must have had over ground movement. Constructed in a 44’ x 46’ excavation, the enlarged shaft boasts concrete side walls faced with blue brindles, bonded together with ironwork. At no point is their thickness any less than 5’, and at the base exceeds 8’6”. Estimated at £2,000, the scheme’s final cost was £2,904, suggesting perhaps that the scale of the challenge was initially misjudged.

A passing thought should be spared for one member of the workforce who lost some of his false teeth during a dinner break; they became lodged in his throat. Unable to extract them, the unfortunate man made the journey to Bakewell where Dr Fentem had to force them down.

A final substantive step in the tunnel’s structural evolution was taken in October 1913 when a project was started to slew the tracks and insert 46 additional refuges in preparation for the introduction of new 9’3” wide stock. Lasting eight months, the work cost £555. 1923 saw the drawing-up of plans to provide a timber lining in No.4 shaft although there is no evidence of the work having subsequently taken place.

Decline and renewal?

Whilst the 1963 Beeching Report prompted the withdrawal of local Matlock-Buxton/Manchester services, the line’s complete closure to through traffic was determined by a confidential 1964 study into ‘duplicate’ trans-Pennine routes and the introduction, in April 1966, of electric haulage for Manchester-Euston services on the West Coast Main Line. From October that year, freight and parcels no longer rattled through the tunnel, diverted instead via the Hope Valley line. The anticipated announcement that passenger expresses would follow was not long in coming, and so on Saturday 29th June 1968 – a day early thanks to a guards’ dispute – 1H18 St Pancras-Manchester Piccadilly became the last train to endure Haddon Tunnel’s darkness at about 7:45pm. The Up line was lifted in June 1969; recovery of the Down took place the following summer.

Perhaps it is testament to those who built the tunnel – now bricked up and ignored for over 40 years – that it has survived the withdrawal of substantive maintenance largely unscathed. The failure of a field drain crossing the bored section has triggered extensive spalling of the brickwork for 100 yards, a function of water penetration and freeze-thaw action. But the decline is sufficiently limited for its reopening to be pursued as part of an extension to Derbyshire’s Monsal Trail, occupying the trackbed northwards towards Buxton and passing through six other tunnels. Landowners are cooperative and surveys have been conducted; planning and financial hurdles are yet to be overcome.

John Millington, George Buckley, James Bird, James Clarke and young Alfred Plank are honoured by a simple memorial in the churchyard at Rowsley. Their efforts, against the odds, were not unique; neither was their sacrifice. But were it not for their like, we would have no railway network. So when you next travel, don’t just gaze at the train – look under it, above it, around it. Celebrate the work of the humble navvy. And if you end up labouring on the green tunnels of High Speed 2, give thanks for the technological and mechanical revolution of the past 150 years. Count your blessings for health and safety too. Yes, really.

Many thanks to Glynn Waite of the Rowsley Association and Dave Harris from the Midland Railway Study Centre for their considerable help with this story.

Published 1st August 2012

More Information

| Peak Cycle Links | Proposal for Monsal Trail use |

| Peak District Planning | Documents relating to the planning application |