Glenfield Tunnel

Glenfield Tunnel

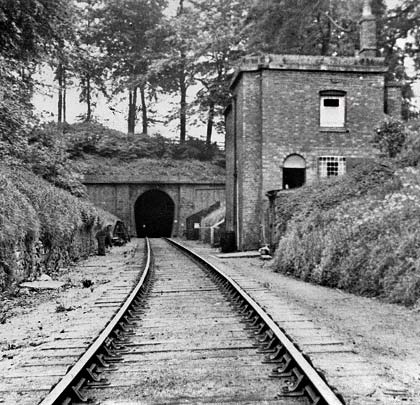

Local coalmasters were the force behind the Leicester & Swannington Railway, its construction marking a tipping point in their battle with rivals further north who were enjoying the logistical and economic benefits offered by the canalised River Soar. Engineered by Robert Stephenson, the 16-mile line opened an artery into the county town from a coalfield to its west – a journey which was previously impractical for loads of any volume, thanks to the terrain. Joining Glenfield Tunnel as the route’s most notable features were a self-acting incline and a second, steeper incline worked by a stationary engine.

A trio of contractors lead by Buxton’s Daniel Jowett sealed their deal to excavate the tunnel on 26th November 1830. Much would rely on their experience. But they soon fell behind the ambitious schedule. Trial borings, upon which estimations had been made, pointed to the presence of solid rock and no requirement for a lining. Reality proved different. Towards the western end, running sands extended for 500 yards. Twenty thousand bricks were despatched to site each week in the vain expectation that 36 yards of tunnel could be completed before the next batch arrived. Three working shafts became four in an effort to catch up. It was down one of these that Daniel Jowett fell to his death.

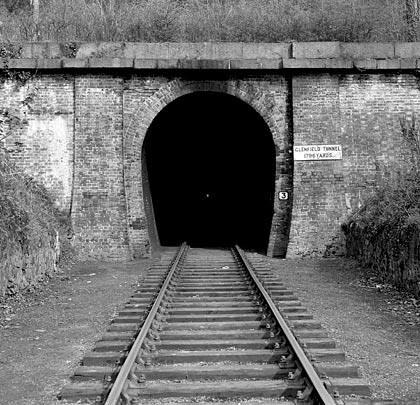

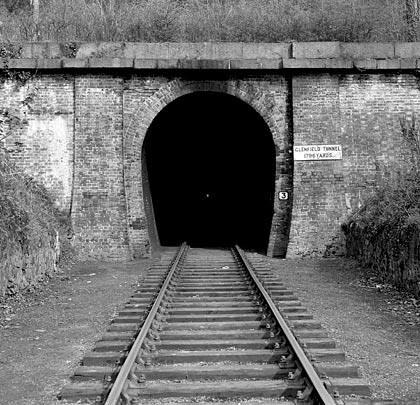

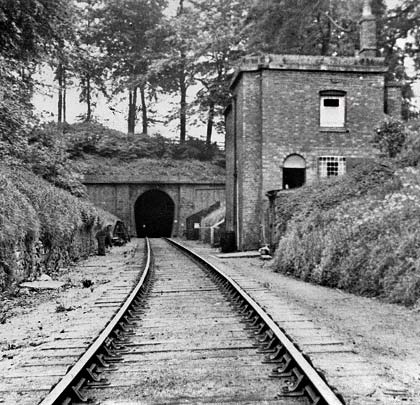

Over budget to the tune of £7,326 – around £575,000 in today’s money – the tunnel welcomed its first revenue-earning train in May 1832. It was lacking the “impressive but not too costly” granite portals craved by its owners, presumably because they proved too expensive.

It was on 17th July that the first section’s official opening was marked by a special train for the Leicester & Swannington’s directors and 300 guests. Hauling it was ‘Comet’, a locomotive procured from Robert Stephenson’s company. Though possibly the stuff of legend, it is said that over-packing of the track caused the engine’s funnel to strike the tunnel’s roof, bringing the adventure to a halt and showering soot over those in open wagons.

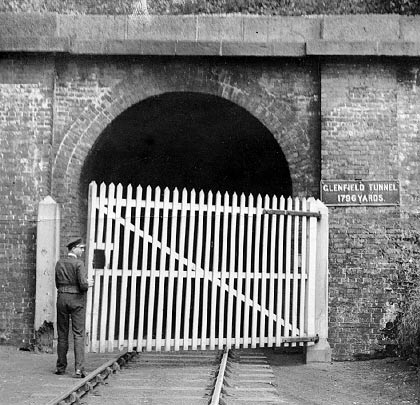

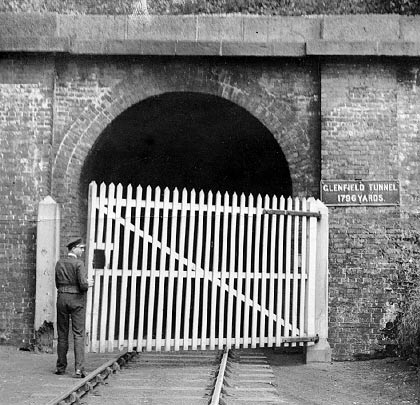

The tunnel proved a draw for the inquisitive, during both construction and operation. High wooden gates kept the public out – these were removed as late as 1929. A favoured dare for young kids was to hide in a refuge while trains passed – a practice which had appalling consequences on one occasion. Glenfield’s tight clearances demanded lower, narrower carriages, with bars over the windows to prevent decapitation.

Closure came in 1966 when coal and oil traffic ended; passenger services had long since been withdrawn. Marconi Radar moved in, taking advantage of the tunnel’s straight mile to test military lasers. But the eastern portal was soon lost beneath infill as its approach cutting made way for housing. One front garden now features a mysterious manhole cover – the only clue as to what lies beneath.

In 1969, Leicester City Council invested £5 to buy the tunnel. Its acquisition has left a substantial legacy. With major roads crossing it and several buildings erected directly above, this asset has to command ongoing attention from the council’s officers.

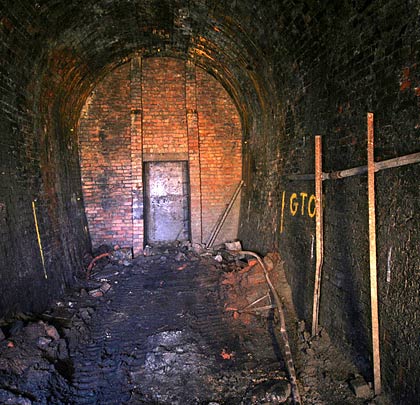

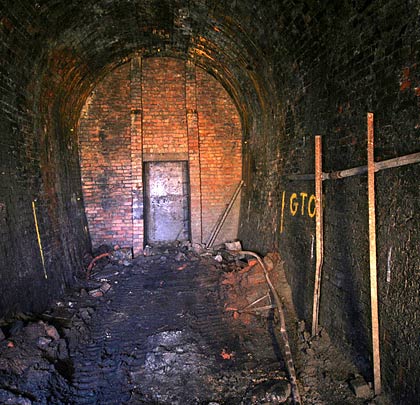

In 2004, Haswells was commissioned to take a deep look at the structure. Cores confirmed the lining to be mostly four bricks thick, though just three in places. Remarkable variations in profile were recorded – as much as 900mm wall-to-wall whilst the roof rises and falls by over a metre. Distortion became most apparent around the 13 shafts, which had punched into the crown. But these and other brickwork discontinuities did not serve as proof that any movement had taken place – Glenfield’s many quirks and foibles could simply be down to its turbulent construction. Two years on, Haswells’ recommendation – to install 38 concrete supporting rings – was endorsed by Scott Wilson Tunnelling. This work has since been completed.

Like the portal, 12 of the 13 shafts are listed. Above ground, the remaining one exists only as a drainpipe embedded within a boundary wall. The deepest plunges over 80 feet whilst the narrowest has a diminutive diameter of just 600mm. Looking after their surface structures is not devoid of difficulty. Many are in private gardens and, although the council retains responsibility for them, it has no right of access. That said, landowners are generally cooperative. Shaft 8 fell victim to a developer some years ago but has since been reinstated. An excavator damaged another during landscaping works, rendering it unstable; that one was dismantled and rebuilt.

Campaigners would like the tunnel’s eastern end to be excavated and a footpath threaded through the bore. There are no indications that this proposal is likely to be progressed any time soon.