Gelli Tunnel

Gelli Tunnel

Through the 1870s, increasing coal production in the Rhondda severely tested the handling capabilities of its monopoly carriers, the Taff Vale Railway and Cardiff Docks. Return journeys were typically taking two days. This background of crippling congestion spurred the merchant folk of Swansea – where new coal shipping facilities had opened – to develop proposals for the Rhondda & Swansea Bay Railway (R&SBR).

Incorporated on 10th August 1882, it established a shorter export route via the Afan valley but, to reach it, the line would have to overcome the River Neath and a 1,700 feet high natural barrier, Mynydd Blaengwyfni. Set that task was engineer Sydney William Yockney; his father, Samuel Hansard Yockney, had acted as engineer and manager for the contractor at Box Tunnel, bringing him to the attention of Isambard Kingdom Brunel for whom he went on to fulfil a number of other tunnel projects.

The construction contract for the R&SBR was awarded to William Jones of Neath in October 1882. Included within it was the construction of the longest railway tunnel wholly in Wales, measuring 3,443 yards. Another tunnel was started to conduct the line for about a mile beneath the River Neath, although this was soon abandoned in favour of a bridge. It’s not surprising then that largely eclipsed by these grander structures was another tunnel of just 164 yards at Gelli, between Cymmer and Blaengwynfi.

Enjoying a falling gradient from the Rhondda, loaded trains clung to the northern side of the Afan valley before disappearing into the tunnel. The first one did so on 2nd July 1890. Horseshoe-shaped in profile, it cuts through a steep spur of land with only around 10 feet of cover at the entrances. A curve to the west of approximately 26 chains in radius is encountered throughout.

Both the portals and lining were originally built in masonry. However two additional brick rings were inserted at the eastern end as part of a subsequent strengthening scheme, presumably prompted by the emergence of defects driven by movement in the superficial deposits above. Refuges were provided throughout, alternating between sidewalls at intervals of 11 yards and exhibiting rock to their rears.

Closure came on 13th June 1960 when British Rail opened short connections to and from the parallel Llynvi & Ogmore line, thus creating a 1.25-mile long bypass around the tunnel and a viaduct which were both affected by mining subsidence.

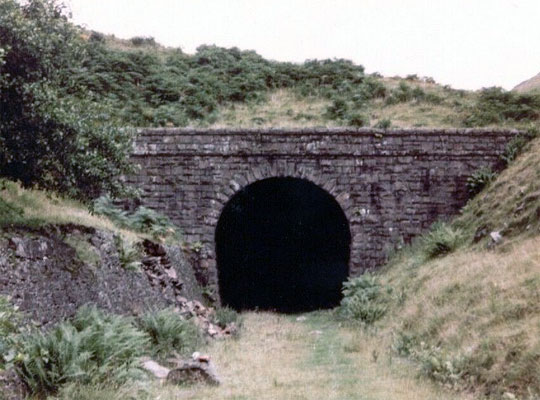

As would be expected, the approach cuttings are now overgrown, with trees and vegetation growth alongside a well-worn path. The minimalist east portal has lost its copings and part of the wing wall on the south side.

Although wet, the section in engineering brick – which extends inwards by about 40 yards – remains in good condition. The larger stone-lined portion, whilst generally fair, has suffered a partial collapse in the sidewall/low haunch of about 6m2, just beyond the end of the brickwork. Revealed by this failure is the rubble backing work and bored face.

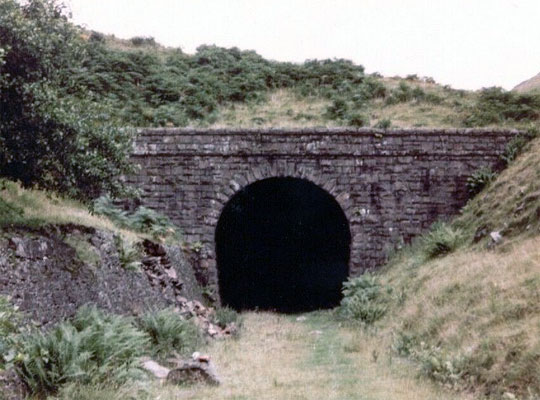

The west portal is intact, with a string course and parapet above the headwall. Some vegetation has established itself, but there are very few cracks or open joints.

(Bill Blair’s photo is used under this Creative Commons licence.)

Click here for more of Lee McGrath’s pictures.