Dudley Tunnel

Dudley Tunnel

Parliamentary authority to construct a line connecting Oxford with the West Midlands was granted to the Oxford Worcester & Wolverhampton Railway (OW&WR) on 4th August 1845 and this was opened in stages between 1852 and 1853. In 1860 the company amalgamated with both the Newport Abergavenny & Hereford and Worcester & Hereford railways to become the West Midland Railway; this was, in turn, absorbed into the Great Western Railway in 1863.

Construction was overseen by the GWR, with Isambard Kingdom Brunel its chief engineer. Progress was slow and by June 1849 all the money raised had been spent with only the middle section close to completion. The Great Western embarked on a legal fight with the Railway Commissioners, prompting the OW&WR to switch its allegiances to the London & North Western and Midland railways in February 1851, signing agreements which allowed those companies to finish and then run the line themselves. However the GWR was successful in challenging that arrangement, thereafter offering the company a similar deal on their own terms.

The death of Francis Tredwell, one of the railway’s contractors, had resulted in a lengthy legal battle with his family firm over financial claims, bringing work to a halt for several years. It took Brunel’s intervention to release the money that allowed his brothers to continue construction work in 1851. And the non-payment of another contractor, Robert Marchant, resulted in disturbances known as the Mickleton Tunnel Riot which prompted navvies to down tools whilst magistrates were brought in to read the Riot Act.

The Oxford Worcester & Wolverhampton was nicknamed the “Old Worse and Worse” and was described by LTC Rolt as a “shocking railway”. On 23rd August 1858, a serious accident between Round Oak and Brettell Lane resulted in the death of 14 people and serious injured 50 more. A Sunday excursion train of 45 carriages, heading to Worcester and hauled by two engines, twice suffered catastrophic failures of the couplings, ultimately resulting in a third of the carriages running loose and becoming derailed. It was described by Board of Trade inspector Captain Tyler as “Decidedly the worst railway accident that has ever occurred in this country.”

Amongst the route’s most significant structures was a tunnel of 948 yards under Dudley. This formed part of construction contract No.4 which was let in April 1846, although trial shafts had been sunk three months earlier. The intention was to complete the work in about 18 months and by January 1847, 80 yards of tunnel had been finished; progress with the remainder was anticipated at a rate of 100 yards per month and this was mostly accomplished. However the external factors described above then intervened.

Dudley Tunnel was driven from five shafts, although none of these was retained for ventilation purposes as the land above was developed for industry and housing. In August 1846, a navvy fell from a skip in which he was descending one of the shafts, resulting in his head almost being severed. January 1848 saw a young man named Taylor break his neck and suffer instant death at the bottom of No.1 shaft when a large piece of timber plummeted from the surface. Six months later, 18-year-old Joseph King fell down a shaft, sustaining fatal injuries. This was a venture fraught with danger. And in May 1847, the 73-foot main span of a new bridge carrying the turnpike road over the tunnel’s northern approach cutting partly collapsed, causing much consternation in the town.

The tunnel is constructed entirely in brick, its northern portal being particularly imposing, presenting a face of 11 brick rings although five of these are probably ornamental. Immediately beyond, corrugated sheeting has been attached to the arch in an effort to manage water ingress. Locally throughout the tunnel, substantial accumulations of calcite and ochre are apparent. Water drips from the lining in several places; this is taken away via a drain running below the six-foot, accessed through open catchpits.

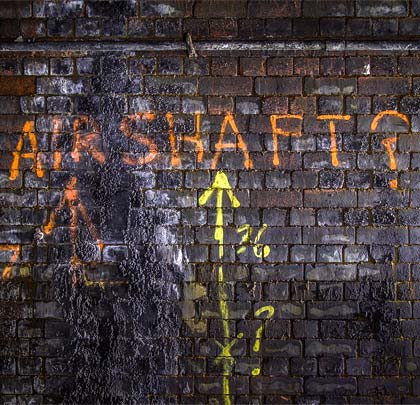

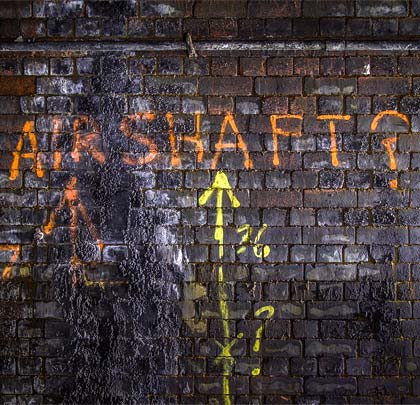

At its northern end, the tunnel curves westwards on a radius of around 40 chains; the remainder is straight. Refuges are inserted in both sidewalls, including one ‘double refuge’ towards the north end. Another has been patch repaired in white ceramic brick. The hidden shafts are identified by markings painted on the west sidewall; there is also evidence of investigation work having taken place, in the form of boreholes at the crown.

The tunnel was used by passenger services until Dudley’s station closed in 1964; however goods trains continued to use the line until 19th March 1993 when the section between Walsall and Brierley Hill was mothballed. A cable laying train passed through the tunnel on 2nd July 1993. Today, access is restricted by palisade gates at its north end, although these are rarely closed. The tracks remain in place but neither is serviceable and a section of the Down line is missing. The Up line is severed in the northern approach cutting.

Proposals to reopen the railway through the tunnel, either as a freight route or part of an extension to the Midland Metro, have not yet to come to fruition. More recently, plans have been announced for a £20 million tram system occupying the trackbed north of the tunnel.