The story of Cwm Prysor: A Family Affair

The story of Cwm Prysor: A Family Affair

Slate was to North Wales what coal was to South Wales – a hidden mineral wealth which fired the imagination of speculators. With the huge quarries of Blaenau Ffestiniog served only by a narrow gauge line to the coast, two standard gauge leviathans set their sights on the town, keen to secure a slice of the lucrative slate action.

with the line etched onto the distant hillside.

Photo: J S Gilks

Whilst the London & North Western arrived from the north in 1881, the Great Western Railway made tracks up from Bala, reaching Blaenau two years later. It never recouped its investment. The 25-mile route took ten years to construct, swallowing money as it went.

Having climbed to a summit of almost 1,300 feet, the line was etched onto a precipitous perch high above the River Prysor as it snaked through the valley. This narrow ledge with occasional rocky cuttings carried the single line for two miles, westwards from a spectacular nine-arch viaduct towards the village of Trawsfynydd.

For a handful of scattered communities, the railway’s arrival opened the door on a new and distant world. “There was nothing else” recalls former guard James Roberts. “There were no motor cars. There were no buses. So the line was the artery between Bala, Trawsfynydd and Blaenau Ffestiniog. Therefore it meant more than we can envisage today. It meant everything.”

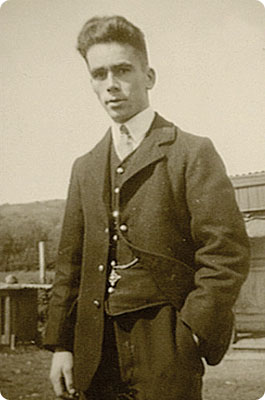

of his railway career.

Photo: James Roberts’ collection

James was first embraced by the GWR family in 1930, starting as a number-taker in Corwen before moving to Bala as a lad-porter. “You met people. People matter don’t they? At least they should. And they did too when the old Great Western was running the show. You provided a service for the community and were part-and-parcel of the whole show.”

Promoted to the role of guard, James would drink-in the rugged Welsh landscape as his train powered its way through the hills. It was a vivid and enduring image. “There is some glory in a steam train – going through these cuttings with a full load and just managing to go. You can see the glory of the steam. There was something in a steam engine which is not to be found in the modern ones. Because with these diesels and electrics, you just put your hand on a button and the thing starts and you’re off. But the other one was alive!”

was marooned during the severe winter

snows of 1947.

Colour photos: Four by Three

After almost eighty years of service, the writing was on the wall for the Bala & Ffestiniog. To slake the thirst of Merseyside, the valley above Bala was to be flooded to form the Llyn Celyn reservoir. Rather than rerouting it, the line was drowned. With traffic receipts so poor, British Rail did not have to agonise too long over its verdict.

The passenger service had already gone when the last freight train made its way down to Bala on the 27th January 1961. James Roberts was the guard. At every station and halt, locals turned out to pay their respects. A funereal gloom descended as social exclusion made an unwelcome return.

As James recollects, “we knew all the people – the farmers and the people who lived nearby – here and all the way to Blaenau Ffestiniog. And that’s the thing that mattered most, when the line finished, you missed ‘the family’. We used to run this place like a family affair and that’s why you had such an interest in your work. There were a hundred families dependent on the railway. Maybe that doesn’t mean a lot in a big place, but in a small town like Bala, a hundred families had to find other work didn’t they? And therefore it was a big blow to Bala. But that’s progress isn’t it?”

The power station at Trawsfynydd brought some salvation. With the 200 yard gap between Blaenau’s two railways bridged by a new link, the line was used to transport nuclear waste for reprocessing. But even this traffic has now ceased.

Further south, nature has taken charge. The rocky ledge clings to the hillside, visited only by wandering livestock and the occasional hiker. It’s a desolate resting place for an engineering marvel.

More Information

| Ffestiniog Railway | The history of lines in the area. |

| Penmorfa | Stories about the Bala & Ffestiniog. |

| Penmorfa | A photographic tour of the line today. |