The story of Clifton Hall Tunnel: Black Harry's Timber Timebomb

The story of Clifton Hall Tunnel: Black Harry’s Timber Timebomb

It’s fair to presume that Monday 13th April 1953 began like any other for ganger E C Nash. His duties that morning held no surprises, or so he must have thought. Ahead of him was a routine inspection of Clifton Hall tunnel, a 1,298-yard tube under the Manchester district of Swinton. It was a grim structure and wetter than most, not that Nash would have been over-bothered after 12 years of regular visits. But that day did prove different. Standing quarter-of-a-mile from its southern portal, he encountered something he’d never seen before.

In 1845, a bill was placed before Parliament for a new line connecting Liverpool with Lancashire’s great industrial towns – Wigan, Bolton, Bury. It would challenge the established Liverpool and Manchester Railway which had enjoyed a stranglehold on traffic between the two cities since the ribbon was cut 15 years earlier.

The LMR conceived its 3½ mile Clifton branch, linking the main line at Patricroft with Bury via Molyneux Junction, as a spoiler. Though it had little strategic value, its promoters thought it would stifle the prospects of their rival. Hindsight showed this belief to be somewhat misguided when the two routes received Royal Assent within a fortnight of each other.

Completed in 1850, the branch settled down to a life of no importance – lost in the vast corporate workings of the London and North Western Railway, its new owner. Passenger trains were withdrawn after a matter of months although freight traffic continued to serve a handful of nearby collieries.

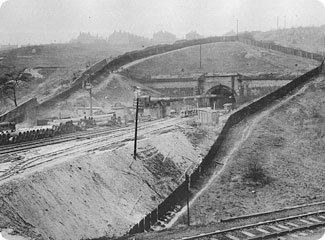

For a fifth of its length, the double track line ran out of sight within the confines of Clifton Hall tunnel – brick lined and straight. Locally it took the name of its dark-whiskered foreman, ‘Black Harry’. Construction was a nightmare thanks to the mix of clay and loose sand through which it had to be driven. Eight shafts were sunk to speed progress. These were later infilled and sealed – none was retained for ventilation or marked within the tunnel. Records of their location remained on file in the District Engineer’s office until they succumbed to the air raids of 1940 and a fire in 1952.

The structure sat 1,500 feet above the area’s coal measures, resulting in some settlement of the structure over time. Coal was first worked from seams below the northern portion. Although no movement had been detected, 617 yards of lining received reinforcement ribs – fashioned from old rail – in 1901.

Conditions became less than satisfactory towards the other end. In the spring of 1912, defects showed themselves around two of the hidden shafts. A specialist tunnel gang rebuilt short sections of wall and arch. Another quarter mile of lining, extending north from the portal, underwent precautionary bracing in 1926, leaving a central section of around 300 yards entirely self-supporting.

The land above remained largely undeveloped until the turn of the 20th century. As part of Swinton’s expansion, 1909 marked the building of a cul-de-sac of semi-detached dwellings, crossing the tunnel at an angle. This was named Temple Drive. Fred and Clara Potter made their home at number 22. Sara Salt and her two daughters, Jean and Emily, lived next door at 24.

Built into the tunnel wall were markers – known as tablets – spaced 50 feet apart and used to identify locations along its length. On the morning of his inspection, Ganger Nash had walked as far as the 29th tablet, 483 yards from daylight, when his attention was drawn to small collection of rubble lying on the Up line. In his experience, despite its flaws, Black Harry had never shed brickwork before. He shone his handlamp upwards. Some of the lining appeared to be peeling away. He made tracks to stop traffic and break the bad news.

All and sundry came to look. First the District Works Inspector, J W Glass, accompanied by the P-Way Inspector. Chief Works Inspector Ashall made a further appraisal. After dinner, E F Boivie, the Assistant District Engineer examined the structure from track level, his boss being on holiday. He concluded that the route should remain closed pending repairs – loss of the little-used line would cause little inconvenience to the operating department. Responsible officers had taken prompt and proper action.

Next day District Engineer A L Owen returned from leave. Together with Mr Boivie and several colleagues, he made a detailed inspection from the top of a wagon. Between a pair of butt joints, two strips of brickwork had fallen from the roof, each 3 feet 6 inches long and 4 feet 6 inches apart, end-to-end. A substantial piece of rotting timber had been revealed, embedded within the lining which, here, was three feet thick. The crown of the arch had sunk by two inches compared with the rest of the tunnel.

Serious strengthening was needed. A draughtsman took profiles close to the defects, completing his drawings six days later on Monday 20th April. He had been diverted by other commitments. Rails were ordered from Gorton works. By this time, their supporting putlogs were already awaiting them, secured in the tunnel wall.

Monitoring took place daily. Little change was noticed until Tuesday 21st when the crown dropped by 3/8 inch. On each of the following two days, a 3/4 inch movement was recorded. Cracks began to develop. Both Boivie and Owen made return visits. The brickwork on the Down side was splitting and flaking in places. A gap had opened between the face and centre rings. It was not looking good. A bridge examiner inserted wedges. Timber props were prepared as a stopgap measure although these were never used as, by the weekend, three sets of reinforcement rails had emerged from Gorton’s workshop.

Plans were made to fix these in place on Sunday 26th. Such were the difficulties encountered that it was late afternoon when the first assembly had been erected on wagons, ready to be pushed into the darkness. It then became clear that insufficient allowance had been made for the tunnel’s irregular shape and ongoing settlement – the ring began to scrape against the wall. After much effort, it was installed 12 feet short of its intended position, clear of the damaged area. Work was then abandoned for the day.

Next morning a draughtsman took fresh profiles and arranged for the remaining rings to be modified at Gorton. These would be fitted on Wednesday – that, at least, was the intention.

The first light of a new day was beginning to paint Temple Drive. It was 0535 on the morning of Tuesday 28th April 1953. At number 21, Police Inspector Kenneth McClennan had not yet risen. Suddenly, from underground, came a sharp cracking noise. He rushed to the window. Across the road was a pair of semis, numbers 22 and 24. As he watched, they folded inwards and disappeared into the ground. The adjacent property, number 26, had its end wall sucked away. A violent rush of air blew clouds of soot and dust skywards.

Within five minutes of McClennan’s alarm, the first ambulances had arrived. Fire brigade and police followed. Locals hurried to help sift through the debris. Confronting them was a crater, 20 feet deep. Into it was tipped timber, tiles, brickwork and a section of roof.

Agnes Williams, the 77-year-old resident of number 26, was lying near the pavement, buried in rubble up to her waist. She was calm and relatively unscathed. Three neighbours pulled her clear. Her maid, Frances Watson, was then seen standing against the wall of her devastated bedroom, alongside an overturned wardrobe. Miraculously, she had survived the collapse despite the loss of her bed. Rescuers soon brought her down.

The community rallied round. Tea and cigarettes were provided. Manpower arrived from a nearby factory. The mayor came to get his hands dirty.

Amongst those in attendance was Whitefield’s Station Master, T Jones, occupant of number 11. It was his call to Manchester’s Chief Controller which kicked the railway into action. District Engineer Owen was underground within 40 minutes. Sixty feet down, a mass of sand and clay completely blocked the passage. Loose brickwork was still falling from the hole in the roof.

It was later in the afternoon that the first body was recovered – Fred Potter, aged 87. Then came his wife Clara, 73, and Jean Salt from next door who, at 28, was the youngest victim. Sara Salt, 69, and daughter Emily, 45, were found still in their beds, 15 feet below ground level. Black Harry had claimed five lives.

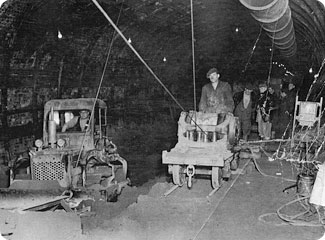

Work to secure the tunnel got underway the following day. Even this was not without incident. Four workers were overcome by diesel fumes after a small concentration of gas built up, caused by lighting equipment. On 1st May, work came to an abrupt halt after more rumblings were heard. But, with ashes packed solidly at either side and timber bulkheads in place, the fall was finally sealed nine days after the roof came in.

operations to infill its barrel. Photo: Coal Authority Archive

Photo: Coal Authority Archive

Brigadier C A Langley conducted the official inquiry on behalf of the Minister of Transport. He concluded that the failure was “in no way attributable to mining subsidence but due to an inherent weakness in the construction of the tunnel.” During his investigations, an old progress plan had been unearthed in the Civil Engineer’s office at Euston. This contained details of the construction shafts which were located by reference to the tablets. Shaft 3 was buried directly beneath the spot where 24 Temple Drive would later be erected.

The timber exposed by the original fall of brickwork formed part of a frame which supported this shaft. It was slowly being crushed by a 200-tonne column of wet sand perched on top of it. This, together with a century of decay, resulted in a massive load being transferred onto the tunnel arch. When the timber finally gave way, the brickwork could not withstand the pressure, allowing the contents of the shaft to break through catastrophically. A vacuum pulled the houses into the void above.

Assistant Chief Works Inspector H Bradley had been making annual inspections of the tunnel since 1947. His detailed notes revealed the conditions between each tablet. In 1948 he recorded hollow and perished brickwork on the Up side, very close to shaft 3. There was also a crack in the arch. Similar reports were submitted every year, together with a recommendation that the remaining self-supporting section should be relined and strengthened with ribs. This was rejected on each occasion after due consideration. Repair funds were included in the 1953 budget but, with the future of the line uncertain and the structure apparently stable, the Divisional Engineer deferred the work.

Swinton’s Register Office after a small

crater opened up in May 2007.

Photos: Martin Kay

Surveys located six of the seven other shafts and assessed the likelihood of further problems. Strengthening was carried out particularly around shaft 4 which was also lacking reinforcements.

The decision to close the branch was not a tough one for British Rail. The southern section shut up shop immediately. When Wheatsheaf colliery bit the dust in 1961, the northern spur was also abandoned. By this time the Coal Board had finished the onerous task of filling the tunnel with colliery waste, brought to a delivery point off the East Lancashire Road. With rails removed and the portals buried, the last vestiges of troublesome Black Harry disappeared.

Or so everyone thought. In 2007, cracks developed in a property occupied by the Swinton branch of Age Concern. It had been erected in the 1930s, directly over shaft 2. With its life almost expired, a decision was taken to knock it down. Then, one May morning, a small crater appeared next to the town’s Register Office. During investigations, drilling had disturbed the tunnel’s lining. A road was closed for several days and five couples had their weddings hastily rearranged. Black Harry could still make its presence felt.

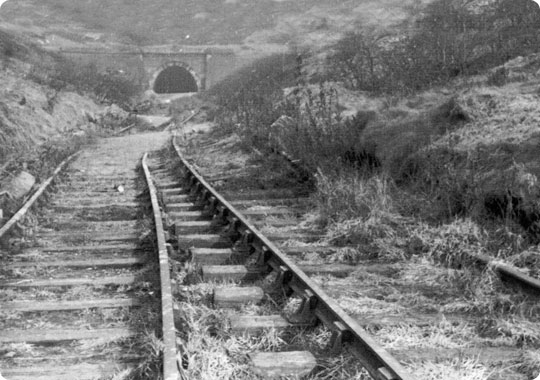

Today a collection of garages mark the spot where 22 and 24 Temple Drive once stood. The tunnel’s southern portal and deep approach cutting have been landscaped to provide a public space. At the north end, vegetation has readopted the trackbed but ground movement occasionally uncovers signs of Clifton Hall’s portal.

This ill-fated structure would never have been cut were it not for the posturing of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, fiercely protecting a position of dominance. When Captain G Wynne inspected it for the Board of Trade on the 28th December 1849, prior to the official opening, he noted that “the exterior appearance of the work gives every reason to suppose that it has been properly constructed.” He could not have known that a timebomb was concealed within its lining. Five souls discovered that more than a century later.

More Information

| Exposing the northern portal | Photos of the northern portal, partly exposed |

| Railways Archive | The official Ministry of Transport report into the accident |

| Bike Rides | Radcliffe to Clifton railway |

| David Flitcroft Photography | Photos of the buried northern portal |