Chipping Norton Tunnel

Chipping Norton Tunnel

The Banbury & Cheltenham Direct Railway was an amalgamation of three schemes built between 1855-87. The first involved a 4½-mile branch to Chipping Norton, built by the Oxford Worcester & Wolverhampton Railway from its main line at Kingham. Then came the Bourton-on-the-Water Railway – a 6½-mile branch heading westwards from Kingham and opening in 1862. Authority was granted in 1873 for extensions to both these lines, creating a through route between Banbury and Cheltenham. The first missing link, between Cheltenham and Bourton, was filled eight years later whilst the second resulted in a railway heading eastwards from Chipping Norton to meet the Birmingham-Oxford line at King’s Sutton. The first train over it – operated by the Great Western – ran on 6th April 1887. The whole route had been absorbed into the GW by 1897.

The line’s construction was blighted by financial constraints and over-optimism. Opposition was encountered from local landowners who resolved to prevaricate as long as possible, before demanding vast amounts of money and concessions from the company. All this resulted in sporadic bursts of construction activity, separated by lengthy dormant periods.

Work on the final section of route – incorporating Chipping Norton Tunnel (BNK/50) – got underway in 1875. Another Act of Parliament, passed in 1877, was needed following difficulties with the alignment and associated land purchases. W J Lawrence, the contractor, was suffering financial problems, resulting in the B&CDR ending its arrangements with him late in 1876. But the railway company was also struggling to make ends meet, resulting in precious little work taking place throughout 1876 and 1877. By this time, some progress had been made with the tunnel, including the sinking of at least one shaft.

August 1877 brought the death of Edward Wilson, the engineer; three months later, another contractor, A Terry, had his contract terminated. Appointed as his replacement was Henry Lovatt but before he could start, the company suspended work on the route’s eastern section. Lovatt continued to carry out maintenance of the tunnel workings, having received a small sum for this purpose.

A further Act of Parliament was obtained in 1879, enabling the company to raise additional funds. When activity resumed, it was focused between Cheltenham and Bourton as this was deemed to be more commercially viable. As a consequence, progress with the tunnel – which had been suspended since September 1876 – was not made for another seven years. A Receiver was appointed to run the B&CDR’s affairs in 1881.

Initially planned to be 484 yards long, an extension to the tunnel had been authorised as part of the July 1877 Act, increasing its length by around 150 yards. An inspection of the workings took place in January 1883, with a view to work restarting under another contractor, C E Daniel. By May, miners were busy underground, with an additional shaft having been sunk near the south end and a heading being driven towards the centre shaft where a section of tunnel had been completed prior to activity being halted seven years earlier. A third shaft was active near the north end.

On 1st August 1883, the company agreed a variation with the contractor, increasing the tunnel’s length once again, this time to 715 yards. On the last day of that month, a navvy’s hip bone was broken after a large piece of timber sprung out and hit him as he assisted with the removal of centring from a length of completed arch. The heading was through soon after and most of the construction work had finished by the following May, only for works to be suspended again before the south portal had been erected.

The company’s continuing monetary constraints affected progress along the rest of the line. It was not until September 1886 that Major General Hutchinson inspected the route for the Board of Trade and a further six months had elapsed before the first revenue-earning train ventured through the tunnel. It remained operational for just 75 years, with closure claiming it on 3rd December 1962.

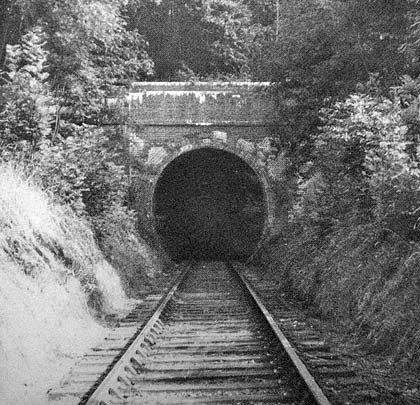

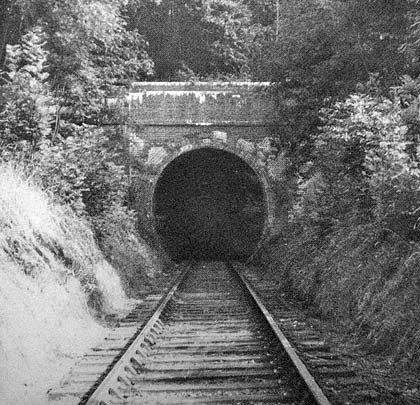

Horseshoe-shaped in profile, the structure is entirely brick-built, with a lining comprising six rings. A falling gradient to the south of about 1:100 is incorporated, together with a curve of approximately 22 chains radius through the southernmost 190 yards.

Both portals feature buttresses and curved wing walls either side of the entrances. The northern approach cutting has been substantially infilled, resulting in only a portion of the tunnel mouth being visible. This is secured with a blockwall although a grille has been installed for inspection access. At the south end, the original wall has been replaced with one of half-height, above which are horizontal bars to allow bats to enter. The tunnel acts as their hibernaculum. There is also a high-level gate.

Inside the tunnel is very wet. Extensive calcite deposits are apparent, particularly on the east wall. Refuges are provided on both sides. No sign of the three construction shafts is visible. The infilling of a bridge between the tunnel and former station site has resulted in the southern approach cutting flooding; standing water extends back into the tunnel.

In early 1990, subsidence affected the surface of a minor road to Elmsfield Farm which crosses the tunnel. Engineers attributed this to fines being washed into it by water ingress. There is also distortion of the arch below a track at the north end.