How the future could bring testing times for Catesby Tunnel: Get your motor runnin'

How the future could bring testing times for Catesby Tunnel: Get your motor runnin’

When it comes to changing the world, Karl Benz did a better job than most. Patented in 1886, his Motorwagen might have borne little resemblance to the vehicles we drive today (three wooden wheels, no gears, 8mph top speed and an aversion to hills) but the Mark III made history as the first commercial automobile. And we all know where that led. By the late 1890s, Benz was established as the planet’s biggest car company even if annual output was fewer than 600 units. Some revolutions take time to gain traction.

Closer to home, Sir Edward Watkin made his greatest mark concurrently with Benz, but it was more transient and not so far-reaching. He was the ambitious tycoon who drove forward Britain’s last main line from Annesley, north of Nottingham, into the capital. This was the Great Central’s London Extension – a 92-mile route engineered for speed, with gradients through its southern division never stiffer than 1:176 and every curve (bar one) enjoying a radius of a mile or more. It put Marylebone Station on the map as a destination for freight. But the post-war dawn of cheap motoring did for it. Express services were lost in 1960 and the line north of Calvert Junction mostly succumbed in the late-Sixties.

Photo © 2006 Philip Weston

Set against this backstory, it seems almost perverse that the London Extension’s most substantial survivor might somehow play a future role to the betterment of road vehicles. That though is the emerging prospect for Catesby Tunnel in Northamptonshire which stands as a monument to the local Estate owner, a chap named Attenborough, and his insistence that the Great Central’s belching locomotives – and the thousands of tons of freight they hauled – did not spoil the view from his stately pile. There’s no hill that a cutting could not have overcome.

Clear air

Like new trains, every part of the bodywork on the car you drive today will have been through a programme of design, testing and modification to ensure optimum performance. Trouble is, the only way to verify that is through simulation using computational fluid dynamics and rolling-road wind tunnels. Despite their increasing sophistication, both have limitations as neither bring with them the true characteristics found in the real world. What you need is a full-sized car running on a road, but with total control over environmental conditions to achieve absolutely repeatability. At 1.7 miles in length, making it the country’s 14th longest ‘classic’ railway tunnel, Attenborough’s folly presents the opportunity to do just that.

Rob Lewis awoke to Catesby’s potential five years ago. A mechanical engineer by trade, he’s the managing director of TotalSim, an engineering consultancy which specialises in aerodynamics, developing both road and race cars. But the work is all computer-based. What his clients need to determine – through physical tests – is the impact of each design iteration on drag, cooling, downforce and the like. Currently that involves straight-line testing outdoors where measurements are obviously susceptible to a host of undesirable external factors, or buying time in an expensive wind tunnel of which there is none in the UK with a rolling road and large enough working section for road car development.

“Wind tunnels are not without their compromises and approximations”, Rob asserts. “You’ve got to try and replicate air that you would see on a road; you’ve got to drag the ground along with a belt; you’ve got to blow the wind as flat as you can; you’ve got to restrain the vehicle without disturbing the air; then you’ve got to measure the forces. The wind tunnel itself is squeezed around the car so there’s always blockage which distorts the air. Catesby Tunnel has blockage too but it has a much bigger cross section (40m2) and you don’t have the constraints of the wind not being perfect or big chunks of metal holding the wheels in place. Here you would have the real car on a real road with its engine running, and all the effects a running engine brings.”

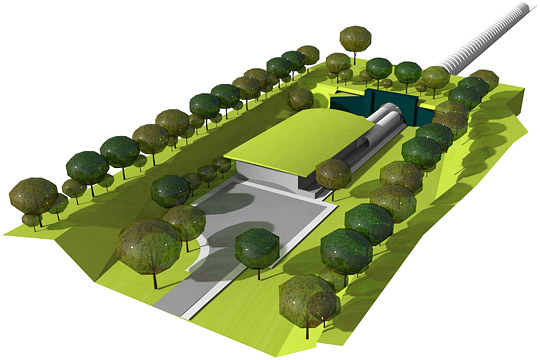

Visualisation: Four by Three

Bear in mind the objective is to accumulate tiny, incremental improvements that trim hundredths of a second off lap times or make fuel consumption and CO2 figures marginally more attractive than your competitors’. So the need is for a tool that can identify very small gains and losses, capturing reliable data to see which direction you’re heading in.

To this end, Chip Ganassi Racing – with teams in the Indycar, NASCAR and Tudor United Sportscar series – has already proven the concept of going underground, converting Pennsylvania’s Laurel Hill Tunnel for aerodynamic test purposes in 2004. Built for a railway that never came to fruition, the facility it now hosts is generally kept under wraps and is not available for normal commercial use. It’s clear though from emerging figures that some of the results it produces are revelatory.

Catesby has greater potential as its working length (taking into account acceleration and deceleration zones) would be more than four times that at Laurel Hill, with a 41-second run possible at 100mph. As a business enterprise, exclusivity would not be an attractive option: the intention here is to interest as many users as possible, noting the happy coincidence of the tunnel’s location close to the centre of UK car manufacturing. And just 13 miles from Silverstone, there’s another market for it on the doorstep.

Heavy going

Transforming Catesby for its new role will bring challenges, just as its construction did. For the most part, it was progressed full-sized from nine shafts, five of which were subsequently retained for ventilation purposes. But Attenborough, adamant that his privacy must not be disturbed by landscape upheaval, would not allow any shafts close to his home near the north end, thus requiring 264 yards to be driven by means of a bottom heading and five break-ups. Unfortunately ground conditions here were at their heaviest, resulting in one collapse and constant breakages of the supporting timbers. This had the effect of disturbing the superincumbent material and greatly increasing the pressure, in turn necessitating more timbering and a thicker lining.

Visualisation: ARP

By comparison, the remainder of the tunnel proved easy going. Cut through by the shafts, the higher rock beds discharged a modest 80 gallons of water per minute into the workings, much of this being pumped to a local garden and farm. The last length was keyed on 22nd May 1897 – just 27 months after the first sod had been turned – giving an average monthly advance of 110 yards, a rate that was almost unprecedented.

Nearly half-a-century in redundancy has done all the things you would expect to the tunnel. Debris in the p-way drain has caused flooding beyond the northernmost shaft; extensive calcite and ochre deposits continue to form due to the withdrawal of maintenance on the water management system; the portals’ brickwork has deteriorated, in part due to tree growth above. But nothing is significant or beyond repair; all the reports suggests it’s substantially sound.

Wheels in motion

Plans for Catesby’s revival have been developed by Aero Research Partners (ARP), TotalSim being one of the two collaborators. There are two distinct elements: the testing facility in the converted tunnel – for which a lease has been negotiated – and a science park on the site of Charwelton’s former station. This five-acre plot has already been acquired, along with the half-mile of trackbed and approach cutting which link the two together.

The tunnel works would be relatively straightforward: make good the drainage, level off the formation and lay the roadway, install crash barriers, lighting and liners to manage any ingressing water, and cap the shafts at their base with steelwork, thus controlling the air flow. There’d be a bank of fans at the north end to provide ventilation and purge carbon monoxide, as well as complying with fire regs. Beyond an air-lock, an access duct would connect the tunnel to a control building in the southern approach cutting, inside which vehicles would be prepared.

Things are currently at the ‘concept-plus’ stage, initial discussions having taken place with local planners. They seemed very positive, no doubt recognising what this would bring in terms of new businesses, high-tech jobs and kudos, particularly if the science park got the go-ahead offering workshop and office space. The detailed design will take another nine months, a process which will run alongside the search for funding. Build costs are estimated at between £5-10 million, depending on which options are pursued. You’d like to think customers, investors and government would all see the potential.

Photo: Four by Three

Whilst Rob has no doubts about the facility’s earning capacity, it does stand outside the recognised comfort zone; that’s the downside of being genuinely unique. There will consequently be a process of manufacturer acclimatisation, convincing them of the benefits of doing things differently. But at very least the savings to be accrued from no longer shipping vehicles and people over to Germany’s rolling-road wind tunnels should ultimately prove an incentive.

ARP’s promotional literature insists “Catesby Tunnel is set to become the world’s premier full-scale vehicle testing facility.” There are many obstacles to negotiate before it can live up to that billing but this kind of innovation and enterprise deserves to succeed. The tunnel’s only other option is perpetual decline and it doesn’t warrant that.

There must presumably have been a time when someone took a financial punt on Karl Benz; history records that to have been a pretty smart investment. Let’s hope someone has the vision to help ARP secure a small part of Sir Edward Watkin’s legacy.

More Information

| TotalSim aerodynamic test facility | An overview of the tunnel plans |

| Catesby Tunnel | Forgotten Relics’ photo gallery |