Ashby Tunnel

Ashby Tunnel

Opened in 1804, the Ashby Canal formed a 31-mile connection between the Coventry Canal at Bedworth and the mining districts around Moira in Leicestershire. Towards its northern end several tramways were constructed to serve local colleries, canal spurs deemed too expensive due to the cost of providing the necessary locks.

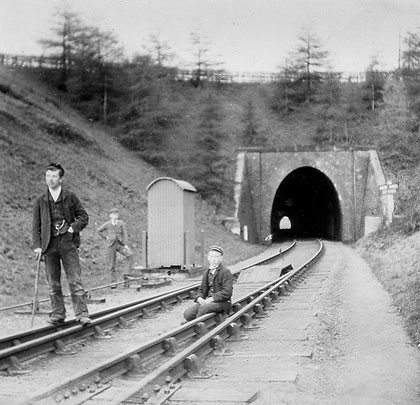

The core double-track tramway, a product of renouned Derbyshire engineer Benjamin Outram, headed north-east through Ashby-de-la-Zouch, thereafter entering a tunnel of 447 yards at Old Parks before splitting into single-track branches – one continuing on to Cloud Hill via Lount whilst the other reached Ticknall. These connected local brickyards and lime quarries with the canal at Willesley Basin, taking the form of a 4 feet 2 inch gauge plateway with angle iron rails set on stone sleepers. Many of these remain extant throughout its 12½-mile length. The wagons – which also carried coal and other goods – were hauled by horses.

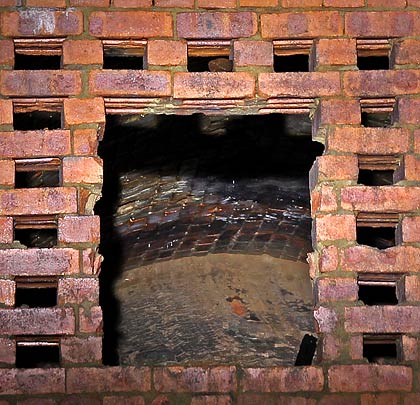

Overseen by engineer John Hodgkinson, work on the tunnel’s approach cuttings was authorised in September 1799, although Outram had “a company of good miners” waiting to be employed on them six months earlier. It was stipulated that the tunnel’s side walls must be at least 18″ thick, the arch 13″ and the invert 9″. The width at track level should be no less than 11 feet. The first traffic passed through in the second half of 1802. Two years later, the feasibility of creating a shaft to provide more light in the tunnel was investigated but went no further.

In 1845 the Midland Railway, anxious to keep competitors away from the Leicestershire coalfields, bought the Ashby Canal and its associated railways for £110,000. It then forged a line from the Leicester & Swannington at Coalville, through Moira to its recently-acquired Birmingham-Derby route at Burton-upon-Trent. One clause of the agreement required it to “keep the canal intact and in good repair for the purposes of trade until the completion of the railway and as long after as may be deemed expedient”.

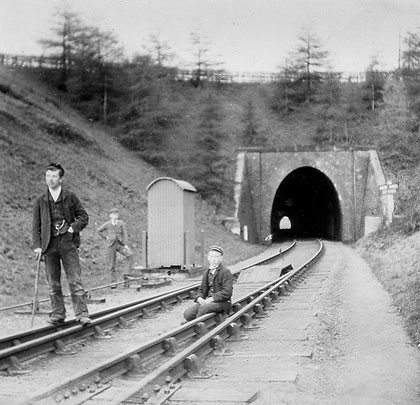

20 years on and the Midland obtained an Act to extend its Worthington branch southwards into Ashby where it would connect with the Leicester-Burton line. This was laid mainly on the trackbed of the Cloud Hill tramway except for a few places where it was realigned to ease the curvature. The tunnel was rebored to accommodate a standard gauge track and, as part of this work, it was shortened at its western end. When the new railway opened on 1st January 1874, just 308 yards of it remained.

The route to Ticknall was not converted, requiring goods to be transhipped at a wharf located close to the tunnel’s eastern entrance. A dwelling, appropriately named Tunnel House, was built there, together with a weighbridge. This arrangement continued until the tramway’s last use on 20th May 1913, although it was not officially closed until September 1915.

The section of line between New Lount Colliery and Ashby – passing through the tunnel – had lost its regular traffic prior to the Second World War but was thereafter used by the Army. The route was returned to the London Midland & Scottish Railway on 1st January 1945 but traffic did not resume. The last train is thought to have been a rail tour on 28th June 1952; official closure coming on 9th May 1955.

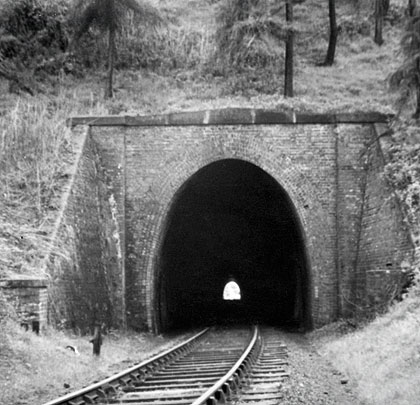

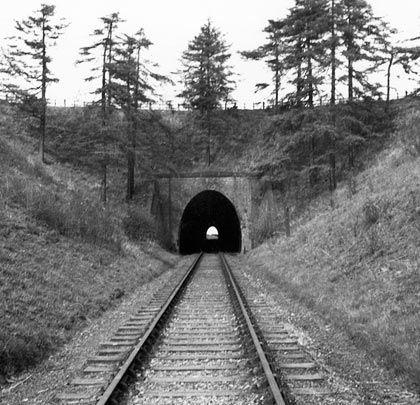

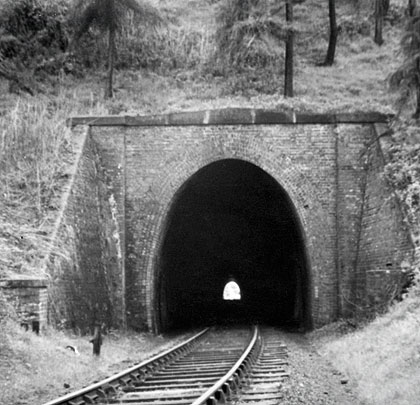

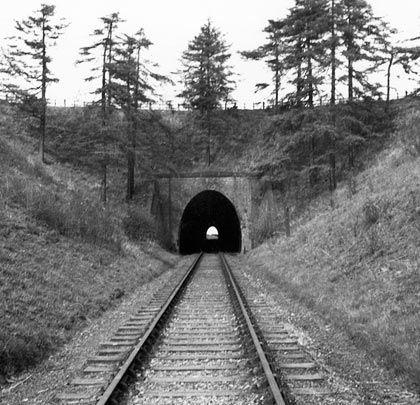

Falling to the west on a gradient of 1:355, the tunnel is straight and horseshoe shaped in profile. Burial of the west portal took place in the late 1970s when the approach cutting was landfilled. Its counterpart at the east end is brick-built with stone copings and triangular wing walls parallel to the trackbed. At the foot of the north wing wall is a short brick column, the purpose of which is unknown.

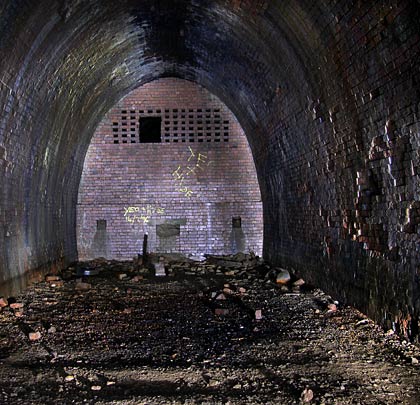

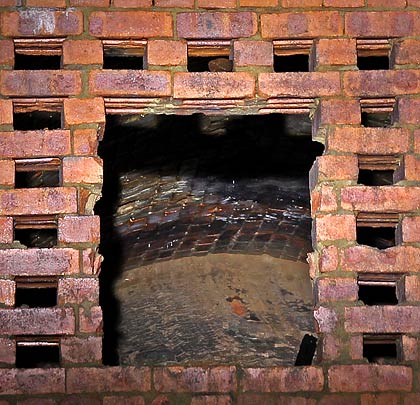

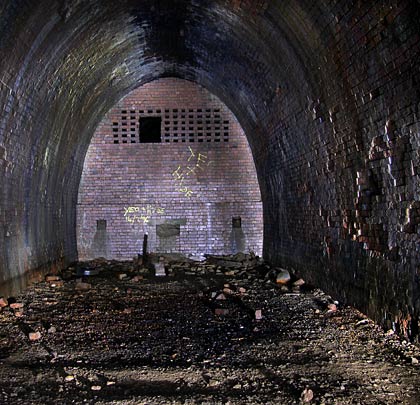

The lining appears to comprise six rings of brick, with refuges cut into both walls. Water ingress was a considerable problem during the tunnel’s operational period and continues to be so today. Numerous weep holes were inserted to allow ground water to drain away. Spalling of the brickwork has occurred throughout although this is most apparent on the north wall where running water has made its mark. As a result of the gradient and infilled approach cutting, it is common for the tunnel to be flooded westwards of its half-way point.

Despite the passage of time since the track was lifted, indentations from the sleepers remain pronounced in the floor.