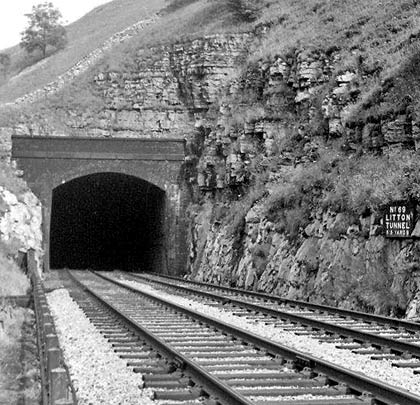

Litton Tunnel

Litton Tunnel

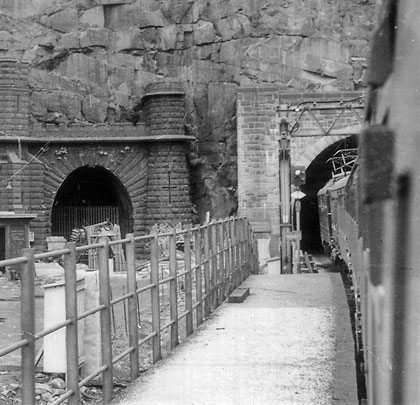

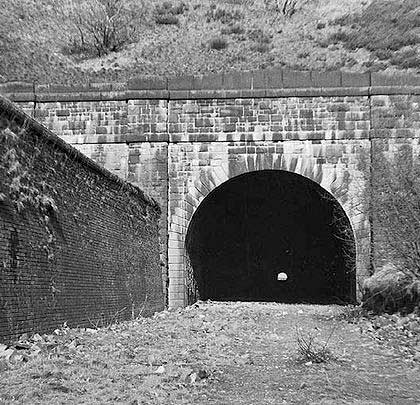

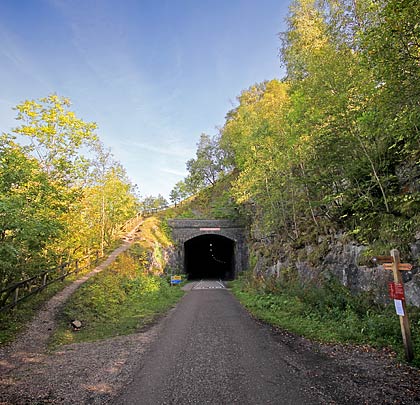

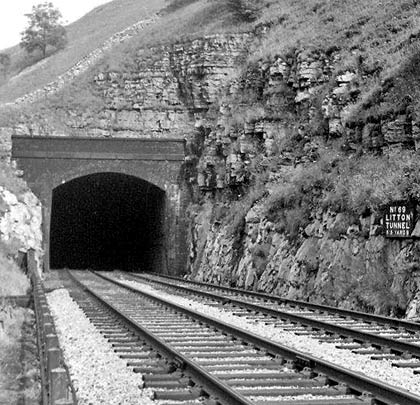

The land rises sharply to the tunnel's south side, ensuring only a short northern approach cutting had to be excavated.

(Photos 13 & 14 © Peter Green, Railway Correspondence and Travel Society (RCTS)/Courtney Haydon Collection)

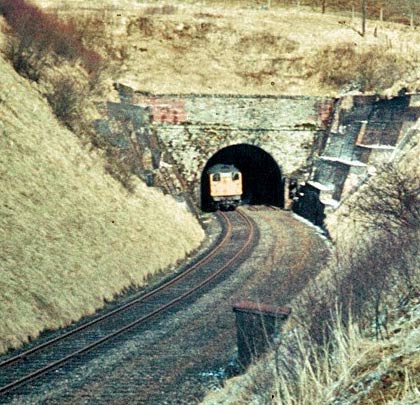

30th May 1863 saw the opening of an exceptional section of railway, eventually forming part of a main line link between London and Manchester. Built by the Midland, it cut a route through the limestone landscape of Derbyshire’s Wye Valley between Hassop and Buxton, demanding eight tunnels totalling 2,426 yards, two major viaducts and a number of smaller ones in the space of just 11 miles. But the audacity and investment did not live long. Barely a century after it opened, most of the route became an unlikely victim of the Beeching-era cuts, officially closing on 1st July 1968.

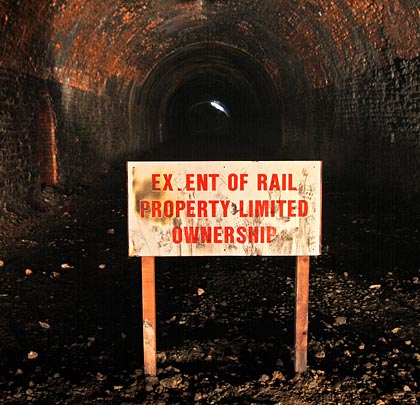

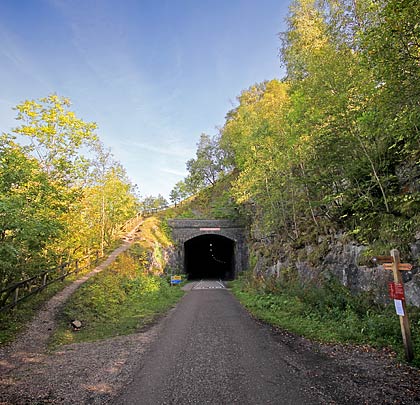

In 1981, the Peak District National Park Authority concluded lengthy negotiations with British Rail to secure the trackbed. Along it was laid the Monsal Trail – a nine-mile path linking Blackwell Mill Junction, east of Buxton, with a bridge over Coombs Road on the Matlock side of Bakewell. Since the summer of 2011, four of the tunnels – which had previously been closed for safety reasons – have been opened up for walkers, cyclists and horse riders to use, creating an easy linear connection between the Trail’s two ends.

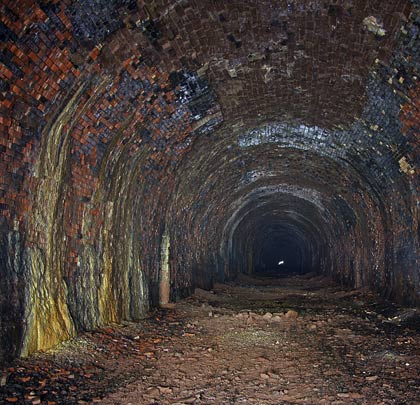

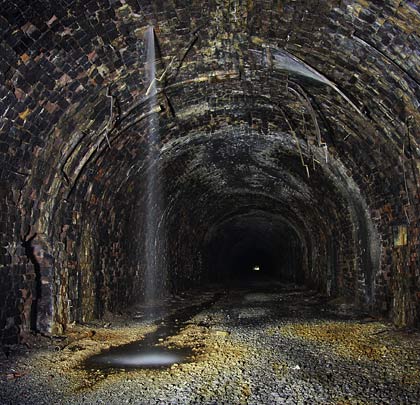

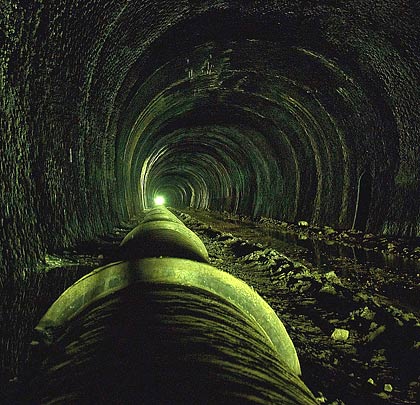

Litton Tunnel, structure number 69, follows a curved alignment, extending for 515 yards. Neither approach cutting is long thanks to the steeply rising hillside on its south side. At the east end, the cutting features impressive vertical rock faces.

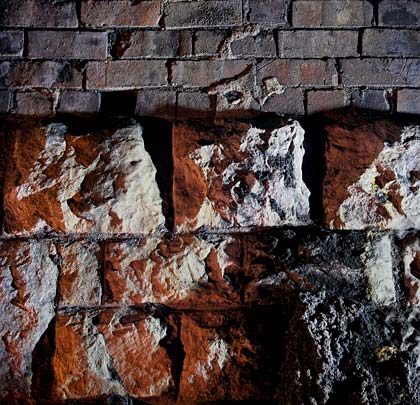

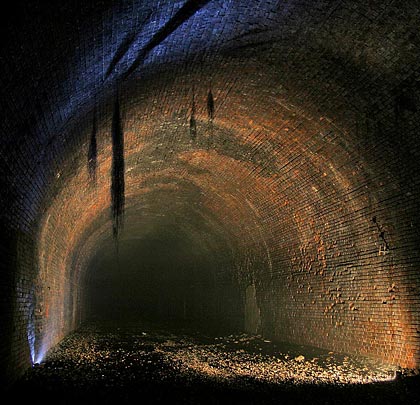

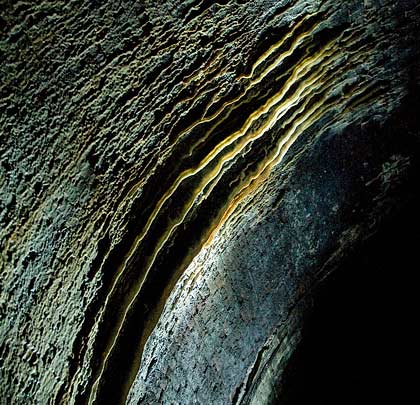

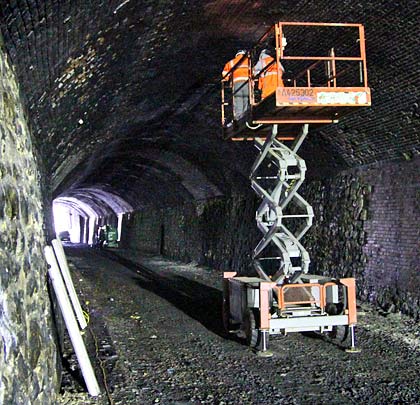

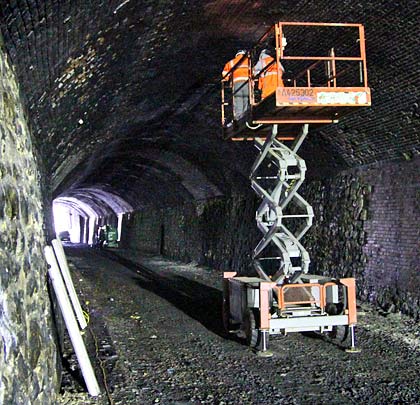

Westbound trains encountered a very short straight section before a long southerly curve of 40 chains radius. The gradient throughout rises at 1:100. The predominant lining material is engineering brick although patch repairs – some of them extensive – have been carried out in both red brick and masonry. The tunnel’s segmental roof arch is supported on limestone walls which lean outwards at the top. At the west end, a change in section sees much higher side walls and an arch with a very shallow rise.

Refuges of inconsistent sizes are provided at both sides. The installation of a 12″ concrete-encased water main, located at the foot of the south wall, was authorised in 1979. One refuge in the south wall leads to a short chamber, reputedly cut in connection with mining activity. Whilst generally dry, small deposits of calcite are found in places.

January 2013

January 2013

Litton Tunnel

Yelverton Tunnel

Damp, overgrown and devoid of sunlight - Yelverton's north portal.

(Photos 13 & 14 © Peter Green, Railway Correspondence and Travel Society (RCTS)/Courtney Haydon Collection)

The broad gauge South Devon & Tavistock Railway was constructed in the late 1850s, opening to traffic on 21st June 1859. It featured six viaducts and three tunnels. The Princetown Railway then drove a meandering line southwards to connect with the SD&T at Yelverton, opening in August 1883. Almost two years later, after agreement to build it was reached with the landowner, a junction station there welcomed its first passengers.

A few yards beyond, the single track penetrated a tunnel, running through it on a straight northerly course for 641 yards. It marked the summit of the main line. The masonry south portal sheltered at the end of its approach cutting. Inside, the rough lining was also fashioned from stone, accommodating signalling wires at a high level. Regular refuges were provided.

The route was converted to standard gauge in May 1892 but the rails became redundant on 29th December 1962 when they succumbed to closure, snowfall curtailing the service and the planned commemorations.

A footpath has already been laid along parts of the former trackbed, with plans being developed to extend it further. It will not however pass through Yelverton’s tunnel which remains as a silent and rather damp reminder of the railway’s former role in the town.

January 2013

January 2013

Yelverton Tunnel

Woodhead Tunnel

Woodhead's abandoned platforms on the western approaches to the new tunnel.

(Photos 1, 2, 4 & 6 © Andrew King, photos 3, 5 & 7© Iain Skinner)

The first of Woodhead’s two single bores, engineered by Charles Vignoles and Joseph Locke, opened to traffic in 1845. It rises on a 1 in 200 gradient towards Dunford Bridge at its east end. Seven years later, the second tunnel was finished.

By the end of the Second World War, they were in such poor condition that Halcrow & Partners was contracted to build a new double-track tunnel. The line was also electrified. After five years work, the ribbon was cut by Transport Minister Alan Lennox-Boyd on 3rd June 1954. It cost £4.6million and six lives.

The little-used passenger service bit the dust in January 1970 but it was not until Saturday 18th July 1981 that a Harwich ferry train became the last service ever the pass through the tunnel.

July 2011

July 2011

Woodhead Tunnel

Withcall Tunnel

A small retaining wall protected the line on the approach to Withcall's western portal which sits in an impressive chalk cutting.

Work on Withcall Tunnel got underway in January 1852 with the driving of a 10-foot heading through sandstone and chalk. The Louth & Lincoln Railway’s original plan was for a bore of 803 yards but this was extended to 971 yards when a revised route was authorised. Construction was beset by problems with bad weather causing frequent delays. In October 1874, a deluge of water washed navvies out of the tunnel. A month later, bricklayers went on strike because their hands were being scalded by wet lime. And December saw the death of a workman who was struck by a wagon.

The first goods train passed through the tunnel on 26th June 1876, with passenger traffic starting in the following December.

The tunnel is straight but no light can be seen at the other end because the summit of this part of the line is located around 300 yards in from the eastern portal. The climb up to and within the tunnel (1 in 54) often caused difficulties in wet conditions – some locomotives required two or more attempts to reach the top. Smoke could become so dense that the footplate crew would kneel on the floor, covering their faces with wet handkerchiefs.

An oversight by the architect resulted in no refuges being constructed – an unusual and potentially dangerous feature for a tunnel of this length.

Today, the portals are bricked up but doorways are provided for access. Humidity levels are high and temperatures stable – ideal conditions for bats. The structure is now a hibernaculum and has SSSI status. Although wet at its western end, Withcall Tunnel remains in excellent condition despite a 50-year absence of regular maintenance. The last train passed through on 17th September 1956.

July 2008

July 2008

Withcall Tunnel

Windsor Hill Tunnel

The south portal of Windsor Hill's original tunnel which was used by Down trains after the route was doubled in 1892.

In 1872, work began on an extension to the Somerset & Dorset Railway, linking a new junction at Evercreech with the Midland Railway at Bath. Costing £400,000, this single track ‘branch’ became the S&D’s main line when it opened on 20th July 1874 as it created a direct link between the Midlands and south coast.

North of Shepton Mallet the line climbed a 1:50 gradient, passing through Windsor Hill in a tunnel of 242 yards. Its construction was attended by tragedy on 18th August 1873, shortly after six navvies started work on the night shift. A block of stone weighing several tonnes fell from the roof, fatally crushing four of the men beneath it and seriously injuring a fifth. Miraculously, the other escaped with only bruises.

As built, the tunnel was largely unlined, exposing its natural lias limestone, but incremental repairs saw discrete sections of wall and roof added, mostly in brick, over the years that followed. The portals are masonry with a few yards of brick arch extending inwards from both. Towards its northern end, the structure curves to the west. Beyond was access into the sidings for two quarries.

Through the 1880s, traffic levels grew quickly. This prompted the line’s doubling in stages. The last section to benefit, in 1892, was Shepton Mallet to Binegar, necessitating the boring of a second tunnel for Up trains. Driven further west with more extensive approach cuttings, this one was shorter at just 132 yards. It is lined throughout with masonry sidewalls and a brick arch. Neat refuges are provided in both walls at regular intervals.

An active campaign to save the S&D was lost in 1965 when the then Transport Secretary Barbara Castle confirmed its closure. Scheduled for 3rd January 1966, it was deferred when one of the operators withdrew its application for a licence to provide some of the alternative bus services; an emergency rail timetable was instead introduced on that date. But on 7th March services on the S&D between Bath and Bournemouth finally came to an end.

Shortly after its closure, Windsor Hill’s original Down tunnel was used to test Concorde’s Rolls Royce engines. In 1968, steel doors were attached for this purpose and, three years later, a sign warned people to stay out because of possible contamination from “radioactive oil”. In 1981 planning permission was granted for the tunnels’ conversion into nuclear bunkers, although this lapsed without being exercised. The doors were removed in 1990 but the tunnel remains fenced off.

The newer Up bore now forms part of a greenway incorporating the nearby Bath Road and Ham Wood viaducts. It is particularly benign, but lacks the character of its neighbour.

June 2009

June 2009A

F

L

U

V

Windsor Hill Tunnel

Whitrope Tunnel

The rarely visited north portal never sees the sun; moisture in the air encourages moss to carpet its stonework.

(Photo 13 © Jeff Grayer, photo 14 © John Lakey)

The Border Union line, built by the North British Railway and known as the Waverley, plotted a course through the often-remote landscape of the Scottish Borders from Carlisle to Hawick where it joined the company’s existing network. Here the first sod was turned on 7th September 1859, the line having been authorised by a Parliamentary Act earlier that year.

The Whitrope Contract, awarded to William Ritson, extended for 4 miles 5 furlongs and within it were two of the line’s most challenging structures: the 14-arch Shankend Viaduct and Whitrope Tunnel, Scotland’s fifth longest at 1,208 yards. Its construction, beneath Sandy Edge, was a remarkable triumph. It climbs a rising 1:96 gradient to the south and features curves at both ends, describing an S-shaped alignment. Rail level is 311 feet below the highest point of the hill, the strata being predominantly red sandstone, with limestone at the southern end. Whitrope Summit, 1,006 feet above sea level, lies 300 yards further Up the line towards Carlisle.

Headings were driven from five construction shafts. 400 gallons of water gushed into the workings every minute; of this, about 216 gallons entered by No.2 shaft alone. To minimise its impact on the work, this influx was managed by a complex drainage system.

At its peak, 600 navvies worked on the tunnel, experiencing huge variations in temperature which caused them to work in coats one minute and topless the next. At least two of them lost their lives. On 22nd April 1859, a ganger named Kingdom chose to descend one of the shafts by rope instead of the ladder provided. About 90 feet from the bottom, he lost his grip and fell, sustaining hideous injuries.

In March 1862, a group of Irish navvies celebrated St Patrick’s Day by stealing all the food and drink from a pub in Longburnshiels, wrecking the place and then attacking a number of Scottish and English labourers who lodged there. The rioting continued for days after.

The tunnel was inspected for the Board of Trade by Captain Tyler on 21st June 1862. Six weeks later, with freight services already running, the route’s formal opening for passenger traffic was marked by a huge banquet in Hawick, attended by upwards of 700 dignitaries.

At its southern end, the tunnel features a modest masonry portal with ashlar voussoirs, projecting band course and plain spandrels, with a tall parapet set into hillside. On the approach cutting’s east side, a vast retaining wall of engineering brick – built as a result of the soft, unstable rock – comprises irregular terraces to hold back the hillside. Inset bricks are laid to form a sloped wall, all benefiting from a rock-faced ashlar supporting wall to ground level with plain copings. To the west is a lesser structure of similar style. The north portal enjoys the same design but the retaining walls are less extensive.

Although the tunnel was originally lined with masonry, substantial sections were replaced in brick over time. However much of this remedial work has itself deteriorated to the point where a large proportion of the bricks have lost their outer face, except where engineering brindles were used. Generally, the lining is in a poor condition, a consequence of the considerable water ingress. Despite all the shafts being hidden behind the lining, at least three of them discharge vast quantities of water into the tunnel through weep holes. The downpipes that used to carry this deluge to the drain have been removed, together with a number of catchment trays. Large areas of calcite are apparent on both walls but there is surprisingly little pondling.

The tunnel still boasts its ballast base, with one open catchpit providing access to the large central drain below the trackbed. Inserted into both sidewalls, which locally are supported on exposed rock footings, are generous refuges of assorted proportions.

At the south end, distortion of the lining prompted the insertion of 16 steel ribs with infill brickwork; several of the ribs have strengthening webs at the crown. However in March 2002, a section of roof immediately to the south of this section gave way, depositing many tonnes of rock and debris onto the solum. Since then the previously-open tunnel has been secured with steel fencing.

The Waverley line closed in January 1969 after which the Up line was soon lifted. The Down line was visited by an engineer’s special on 1st April 1970 before it too was taken up. In recent years, the efforts of the Waverley Route Heritage Association – which has laid a section of track on the approach to the tunnel – have been rewarded with the Grade B listing of the tunnel, affording it some future protection.

Click here for Dick Sullivan’s story ‘Navvymen’ which covers the construction of Whitrope Tunnel and other nearby structures.

January 2013

January 2013A

F

L

U

V

Whitrope Tunnel

Wheatley Tunnel

Wheatley's stone portal contrasts with a serious brick retaining wall.

(Photos 15 © Transport Treasury/Norris Forrest, photos 16 & 17 © Bruce McCartney)

Conceived as part of a grander scheme in 1883, the Halifax High Level and North & South Junction Railway – abbreviated in 1892 to the Halifax High Level Railway – extended for a little over three miles, leaving the Halifax-Queensbury line at Holmfield and terminating at St Pauls Station. Construction got underway late in 1887, requiring a workforce of between 1,100-1,200 men employed by the contractor, Messrs Baker of Bradford.

Two substantial structures were required towards the northern end – a viaduct of ten arches reaching 100 feet in height and an 819-yard tunnel, both at Wheatley. Construction of the latter was not devoid of incident. At noon on 23rd January 1888, with the 10-foot heading having been driven 40 yards into the shale, a rockfall buried two miners. One was extricated within 20 minutes relatively unharmed but efforts to rescue the other were hampered by a second fall. The body of John Potter, aged about 50, was removed three hours later.

In August 1889, the half-yearly shareholders meeting was told that the viaduct’s arches had been turned and its masonry was complete except for the parapets. 620 yards of tunnel had been enlarged to full size, 586 yards of which had been lined.

The inaugural passenger service ran on Thursday 4th September 1890 although goods had been carried as far as Pellon – the only intermediate station – since 1st August. Running northbound, it stopped at the tunnel’s western entrance to allow Mrs Booth, the Mayoress, to unlock the gates with a silver key. There was much rejoicing. This was, however, short-lived as the passenger service linking the higher and lower parts of Halifax lasted only 26 years, ending on 1st January 1917. Goods trains continued to shuttle back and forth until 25th June 1960.

A lengthy brick retaining wall dominates the north side of Wheatley Tunnel’s western approach cutting. The portal is a substantial affair, built in stone and featuring buttresses to both sides of the entrance. The headwall extends above a string course and is topped with masonry copings brought to a central point. The voussoirs are relatively modest.

The tunnel’s interior is lined in brick throughout. Refuges are inserted in both walls although many have been filled with breeze blocks as part of recent remedial works. Around 520 yards from the west end is the only ventilation shaft which emerges to the east of Cousin Lane as a square brick tower. Telegraph cables were carried on the south side wall and many of their insulated mounting arms remain in situ. The tunnels is generally dry, despite which localised spalling of the brickwork has occurred.

The eastern approach cutting has been backfilled, burying the portal. However there is a high-level doorway in the blockwall leading to a concrete access shaft. A mound of rubble extends into the tunnel at the base of which is an area of thick orange sludge.

Click here for more of Phill’s Wheatley pictures.

June 2014

June 2014

Wheatley Tunnel

Wenvoe Tunnel

Knee-deep in muddy water, Wenvoe's northern portal.

(Photo 10 © Phill Davison, photo 11 © Richard Barnes)

The Barry Railway Company was born to release the stranglehold of the Taff Vale Railway and Cardiff Docks on the export of South Wales’ coal. Work on it started in 1885 and thanks to their efficiency, by 1910, Barry Docks had overtaken their near neighbour in terms of tonnage shifted.

Within four years, the company had built a substantial rail network including several branches and an 18½-mile main line from Trehafod into the docks. Included in this was a double-track bore of 1,868 yards at Wenvoe which first saw active service in 1889.

The tunnel is brick lined except for a short section at its southern end where a change in geology occurs. Towards its centre is a single ventilation shaft, also brick lined and almost the full width of the structure.

Traffic through the tunnel came to a premature close on 31st March 1963 thanks to a fire which destroyed Tynycaeau North signal box. Since then, it has become home to a large water main and extraordinary mineral deposits which adorn the walls. A pile of junk has come to rest at the foot of the shaft and the tunnel now suffers badly from flooding, with waters reaching a depth of four feet after heavy rainfall.

Click here for more of Sparhawk’s pictures.

Click here for more of Ben Salter’s tunnel shots (Flickr).

August 2012

August 2012A

F

L

U

V

Wenvoe Tunnel

Well Heads Tunnel

The well-secured south portal boasts access for bats.

(Photos 2-7 © Sparhawk, photos 8 & 9 © Ben Salter)

Construction difficulties brought delay to the extension of the Great Northern’s route from Thornton through to Keighley. The 1½ miles to Denholme was opened as a single-track goods line on 1st September 1882, incorporating two tunnels – Hamer’s Hill and Well Heads, the latter being significantly longer at 662 yards. The through route to Keighley didn’t appear until 1884.

The northern end of Well Heads Tunnel marks the highest point of the line – 887 feet above sea level. The structure boasts characteristic GN stone portals with buttresses either side of the entrance. Inside, vertical masonry-built walls – accommodating tablets and supports for signalling cables on the Down side – give way to a brick arch. Regular refuges, also in brick, are provided. There are no ventilations shafts.

Closure of the Thornton-Cullingworth section came on 11th November 1963.

Part of the northern approach cutting has been infilled since the railway was removed, effectively sealing the tunnel at that end. Its ownership is divided, with the southern section being in the hands of British Railways Board (Residuary). Work to repair spalled brickwork has taken place in the past 20 years.

It is hoped that the Great Northern Trail will eventually be extended northwards from Thornton to pass through the tunnel.

Click here for more of tunnelrat’s pictures.

June 2011

June 2011

Well Heads Tunnel

Wath Road Tunnel

The functional brick portal at the north end of Wath Road Tunnel.

(Photo 12 © tunnelrat)

There aren’t many tunnels that are inspected by boat – literally – but here’s one with which to start a list.

The red brick Wath Road Tunnel was part of the Swinton & Knottingley Joint’s line south from Ferrybridge, linking to routes heading west, east and south from the area around Wath-upon-Dearne. Passing through it was a chord from Dearne Junction to Mexborough West Junction on the South Yorkshire, Doncaster & Goole Railway.

At 62 yards, it is neither hugely significant nor especially impressive. It did though serve its purpose well, doing so from 1879 until closure came in 1965.

March 2011

March 2011A

F

L

U

V

January 2013

January 2013