The story of Scarcliffe Station by Trevor Skirrey: The Last Train

The story of Scarcliffe Station by Trevor Skirrey: The Last Train

Promptly at 9pm on Saturday evening, a passenger guard blew his whistle and held aloft his polished, paraffin-filled hand lamp, displaying a green light to the driver. He acknowledged with a resounding whistle and the train hissed and puffed away from Chesterfield Market Place Station for the last time – nostalgic sounds that would be heard no more.

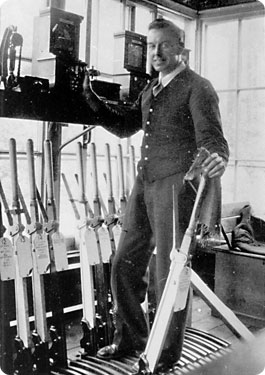

suggesting that the lamp is in need of paraffin.

PHOTOS: TREVOR SKIRREY COLLECTION

An ambitious scheme was conceived by William Arkwright – a local landowner – and other Victorian planners to connect and develop the great coal fields of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. It would bring together the east and west coasts, 175 miles apart, passing through Chesterfield, making it the Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway.

After five years, a line was finally laid from Langwith Junction (later called Shirebrook North) to Chesterfield. The cost of this short stretch of line was astronomical and further funds were unforthcoming so the project ended at the Market Place Station which had a new glass roof, four platforms and great expectations. But a railway would eventually run; ribbon cutting by Mrs Arkwright officially opened the line for traffic on 8th March 1897. Freight trains would serve local collieries and at least seven passenger trains provided a daily service to Lincoln, Mansfield and all tiny stations en route.

In less than 60 years, the very pits which the line was intended to serve wreaked havoc upon it by subsidence, bringing about its quick demise. The terrain was most uneven, necessitating the erecting of bridges, viaducts and tunnels.

The most costly construction between Lincoln and Chesterfield was undoubtedly the Bolsover Tunnel; completely straight for 2,624 yards, emerging at Scarcliffe. Subsidence and water formed the basis of its rapid closure. It constantly dripped water even when the weather was dry. At the Scarcliffe end, I walked down to the tunnel mouth many times to collect fresh watercress!

A special tunnel gang was employed seven days a week, keeping it maintained and under observation. In 1942, only 45 years after its opening, the Up line was deemed unsafe due to water erosion of the north wall, meaning all trains would now travel on the Down line. A single line system was introduced (key token working) and the signal boxes at Scarcliffe and Bolsover Stations were modified to allow this. A leather pouch would be handed to the driver by the signalman containing that ‘key token’ ensuring that his was the only train on that stretch of line.

In that year, the Royal Train from Sheffield was diverted off the London route and directed instead towards Duckmanton and Arkwright Junction. It was night and the train came to a stop inside Bolsover Tunnel. All traffic had earlier been cancelled. Sheffield suffered heavy bombing and it was considered, for obvious reasons, that the Royal Train with King George VI on board would be safer taking cover in the tunnel overnight. Villagers were unaware of this activity except for railway staff. The platelayers, in crumpled greasy caps and baggy corduroys, guarded fences, bridges and viaducts to deter any would-be 5th Column assassin – called ‘the enemy within’ during the war years. The next morning the train continued on its journey.

In 1947, a passenger timetable ran:

| Station | Depart |

| Chesterfield | 4:10pm |

| Arkwright | 4:20pm |

| Bolsover | 4:28pm |

| Scarcliffe | 4:39pm |

| Shirebrook North | 4:43pm |

| Lincoln | 5:52pm |

Fares were low compared with those of today. Chesterfield Market Place to Lincoln – eight shillings and tuppence, or 41p as we know it now (£11.90 if converted using RPI). Scarcliffe to Chesterfield – two shillings and four pennies – 12p in today’s money (£3.40 if converted using RPI).

Probably the first and last station master to be appointed at Scarcliffe Station was a bewhiskered Mr Hunt where he, his wife and three children lived in the newly-built four bedroomed house, situated at the entrance to the station premises which boasted a huge white gate. The Great Central’s station houses were unmistakable in their Edwardian style; built to last.

The station’s pretty island platform contained tiny gardens of roses and bright mesembryanthemums and was the recipient of many ‘Best Kept Station’ awards which were framed and proudly displayed in the waiting room. Quite and achievement considering the number of stations between there and Lincoln!

The historic snows of 1947 not only disrupted life at Scarcliffe but the whole of England itself. The running of trains throughout the system was seriously disrupted for many weeks. When the mountains of snow eventually melted, it was almost spring and water poured from everywhere. At Scarcliffe, it gushed down Fox’s Hill for days. It came from surrounding fields where snow had lain several feet deep, melting into a river. It poured onto the street, past the school and Chapel, and as it passed the Elm Tree Inn it was joined by more water flowing down Main Street. Its course took it down Station Lane, through the station gates, across the railway line and down an embankment on the other side, to merge with the swollen River Paulter.

The force of water washed away yards of ballast from beneath the track and trains were cancelled again. It was many days before fresh ballast was replaced and normal working resumed.

Serious as this was, a huge embankment slip at Arkwright stopped the line for weeks. Passengers detrained at Bolsover and a bus service was provided onwards to Chesterfield. The culprit again was the aftermath of the ’47 snows which caused a high and wide embankment to collapse, leaving the metals hanging in mid-air like two ladders across a precipice. Months of work were involved bringing train loads of ballast and dozens of men to restore support for the tracks. The Down line was eventually made safe for the passage of trains and emergency Single Line Working brought in until the other line was repaired, which was not until late summer. It ran between Arkwright Junction and Markham Colliery, entailing the employ of a pilotman – distinguished with a red armband – to ride footplate over the single line, thus giving the driver assurance that no other train would occupy track at the same time.

Being a signalman, I was temporarily rostered to act as pilotman for several weeks. Riding footplate backwards and forwards made a refreshing change. After accompanying a train to Markham, there would be another waiting to go in the opposite direction so I climbed aboard and the process began again. Close cooperation between pilotman and signalman was absolutely essential and one had to bear in mind the all-important passenger trains to which no unnecessary delay was caused.

In 1951, a decade before the ruthless Dr Beeching took delight in closing many important branch lines, the expensive Bolsover Tunnel was finally declared unsafe. Further maintenance work would be ineffectual as the water ingress was unstoppable. It ran more determinedly through the brickwork and the metals themselves had a tendency to creep due to subsidence. Trains maintaining a strict speed limit were almost scraping the tunnel sides. The end was near. All staff were notified that other places of work would be found for them. The local press publicised the news that from 3rd December 1951 the line would be closed.

And the village folk of Scarcliffe were obviously saddened. The line was still a vital link to those far-away places. There being far fewer cars in those days left for quiet and dreamy roads lined with the sweet fragrance of hawthorne blossom, not diesel oil. The next blow to Scarcliffe came a year later with the closure of its only shop and Post Office.

And so at 9pm the train departed Chesterfield Market Place for the last time. Being on duty that evening to signal it through (it did not halt at Scarcliffe), I watched as it slowly passed by, leaving a skein of smoke drifting across the platform and, through condensated windows, discerned a few railway enthusiasts riding the train for nostalgia’s sake. It was 9:29pm. The engine sounded a long and final whistle to everyone at Scarcliffe before rounding the curve on its way to Shirebrook; its small red tail light – bobbing and flickering slowly – disappeared into the December darkness.

Sunday morning I opened the signal box for the final time to allow engines and wagons up to the station, crowded with gangs of men with dismantling equipment. The tunnel portals and ventilation shafts were sealed at both ends. The station buildings, furniture, signals and signal box – together with the green-painted iron footbridge – were hastily removed and, in three weeks, it was all but a memory, save for my first Train Register which I salvaged from a dusty pile beneath the frame.

In November 1945, after a few years in various signal boxes, I had taken up the signalman’s post at Scarcliffe, remaining there until its closure six years later. My family and I continued to occupy the station house for a further ten years. At night, when winds gusted through the station’s trees, I could swear to hearing sounds of a distant train!

More Information

| Richard’s Bygone Times | Page of photographs showing Scarcliffe village and station |

| Wikipedia | Page about Lancashire, Derbyshire & East Coast Railway |