The story of Hassop Station: Coming home to Hassop

The story of Hassop Station: Coming home to Hassop

It was a rural outpost on the main line from Manchester to St Pancras. Passengers last used it in August 1942. But when it opened, the delightful station at Hassop in Derbyshire found itself elevated – albeit only temporarily – to serve as terminus of the Midland Railway’s Buxton branch which was being advanced through the Peak District, blessed by some outstanding engineering.

Whilst the nation celebrated Olympic glory and locals made tracks for the annual Bakewell show, 1st August 2012 saw around 50 former employees – or relatives thereof – gather at Hassop to celebrate the 150th anniversary of the station’s opening.

Photo: Rowsley Association

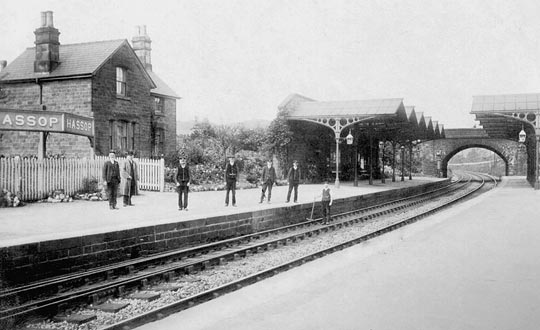

It was an industrious place in its heyday, standing in isolation about a mile south of the village from which its name was taken. Erected on the Up platform, the single-storey main building boasted fine masonry – grandeur reflecting its intended status as host station for the Duke of Devonshire, seated at nearby Chatsworth House. A First Class waiting room was provided for this purpose although, as things turned out, His Grace preferred to catch his trains at Rowsley, four miles further south.

Designed by Manchester architect Edward Walters, elegant canopies offered shelter for passengers – the two platforms being overlooked by the station master’s house on the Down side. Benefiting from a five-ton crane, the adjacent goods yard comprised a shed, three sidings and a loading dock, access being controlled from a signal box at its southern end.

Whilst one railway landscape looks much like any other, Hassop’s stood out thanks to a curious idiosyncrasy. Ganger Isaiah Gilbert is credited with introducing topiary to the trackside in the early part of the 20th century, cutting hawthorn bushes into unusual shapes, often depicting animal life. The tradition continued beyond his retirement in 1930, ending only when the line closed in 1968.

Photo: Rowsley Association

Meagre receipts had brought the withdrawal of passenger services 26 years earlier; goods traffic kept the place going. But there was no halting progress. As road transport caused flows to dwindle, the 1963 Beeching Report accelerated the demise of rural goods yards, bringing Hassop’s curtain down on 5th October 1964. The final shift in the signal box was worked in May ’66. Subsequently leased as an agricultural depot, the site fulfils a mundane function as a car park today. But the building has recently been sympathetically renovated to accommodate a book shop, café and cycle hire business, the latter profiting considerably from last year’s upgrading of the adjacent Monsal Trail and reopening of four tunnels.

Snubbed by the Duke of Devonshire, his waiting room was buzzing on 1st August when some of the station’s former staff arrived to exchange stories about their time there. Others came from across the country to learn about the roles played by their distant relatives. Some had connections to the topiary-crafting platelayers. The Rowsley Association marked the event by publishing a commemorative book, written by Glynn Waite, as well as providing displays charting the station’s history in photographs. The café’s owner, Duncan Stokes, ensured those in attendance did not go hungry.

Ken Reader, whose father was a driver on the line, and Bill Newton recalled their time as relief signalmen, often finding themselves at Hassop. Bill described the scene on Bakewell show days when the goods sidings would be used to stable some of the extra trains laid on for visitors. But whilst Ken and Bill were part-timers at Hassop, Les Harrison (left) was one of three permanent signalmen, working the box from 1943 to 1950. Now 85, he joined the railway at 17, earning five shillings less than his colleagues due to that tender age. One of the daily duties involved collecting water for the box from a pump next to the station master’s house.

The event rekindled old friendships and helped to forge new ones. Like many rural stations, Hassop’s was at the heart of local life, providing employment and, occasionally, a lifeline. “Everybody knew everybody”, declares Les. “It was a happy place.” Although the industry has changed beyond recognition in the years since it closed, memories remain vivid in the minds of former staff who felt part of Hassop’s railway family.

More Information

| Hassop Station | Disused Stations page about Hassop |

| Hassop Station | Cafe, book shop and cycle hire operation |