Nottingham Suburban Railway

Nottingham Suburban Railway

In the 1880s, the city of Nottingham had expanded into its surrounding villages and hamlets which, in turn, had grown into suburbs. These needed to be connected to the rail network. At this time the only competition to the railways came from horse-drawn trams and omnibuses which were slow, could only carry light loads and not travel long distances.

The 1860s and 1870s had seen the unrivalled success of the London underground railway system and its associated commuter lines so, in the late 1880s, a group of Nottingham businessmen felt that the creation of a railway on similar principles would benefit the city’s rapidly growing suburbs.

Historical development

The Great Northern Railway had opened its Derbyshire extension line into Nottingham in 1878; however its principal concern had been to link up the numerous coal mines to passenger traffic. In addition, trains had to make a 7¼ mile circuitous journey from Nottingham, firstly travelling eastwards to Colwick & Netherfield before heading north-west through Gedling, Mapperley and Daybrook to Basford which, on a direct route, was a mere 3¼ miles from the city centre. The Nottingham Suburban Railway, so its backers thought, could complement the Great Northern’s extension line as well as providing a more direct route into the city. An agreement was arrived at whereby the GN would work the proposed line, providing all the locomotives, rolling stock and staff; in return it would retain 55% of the gross receipts. Despite this arrangement, it is worthy of note that the Nottingham Suburban Railway company remained an independent entity until 1st January 1923 when it was absorbed by the London & North Eastern Railway.

Passengers were not the only motivation for the line. One of the leading promoters, Robert Mellors, was chairman of the Nottingham Patent Brickwork Company whose works were on the proposed route at Thorneywood and it was put forward that a branch be built to serve them. This plan received approval from a director of the company, Edward Parry, who would go on to become the line’s chief surveyor and structural engineer. The branch would become the only one of note from the line, running a distance of just 198 yards, of which 110 were in a tunnel taking it beneath Thorneywood Lane before climbing an inclined plane along which wagons were hauled to and from the brickworks.

The company obtained its acts during 1886 and these were strongly supported by Nottingham City Council. By October 1886, Parry had surveyed and staked out the route. Construction work began in June 1888. Some 3¾ mile long, it ran from a junction with the Great Northern Railway at Trent Lane and headed north to another junction with the GN’s Derbyshire extension line at Daybrook. Intermediate stations were built at Thorneywood, St Ann’s Well and Sherwood.

Because of the hilly terrain, the railway proved extremely costly to build, with one-sixth of it built in four tunnels, the longest being just over quarter of a mile long. In addition, there were seven brick-arched bridges, nine girder bridges of which three were over 100ft in span, eight culverts and numerous retaining walls, embankments and cuttings. Construction costs were increased by a third as the Midland Railway insisted that all bridges carrying the line over its metals were at least 50ft wide whilst the Great Northern demanded a flyover at Trent Lane to avoid conflicts on their Nottingham-Grantham line.

Despite these adversities, the line was completed by 23rd November 1889 and opened to both passenger and goods traffic on 2nd December of that year.

The route described

Inbound trains ran from Daybrook via the three intermediate stations and then via Trent Lane Junction into the Great Northern’s London Road terminus. Each of the three stations lay in their own valleys with generous platforms in anticipation of the large-scale commuter traffic which unfortunately never developed.

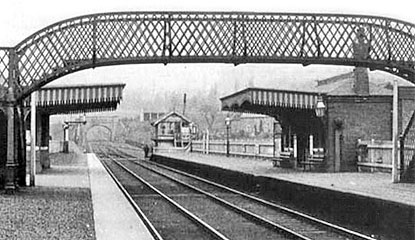

The 70-yard Ashwell Tunnel formed part of the approach to Sherwood Station which had facing platforms built around a curve, spanned by a road bridge and wrought iron lattice footbridge for passengers. The buildings were brick built with wooden awnings and a decorative fringe. The station had its own dock and cattle pen together with a weighbridge and office. The signal box was situated on the Down side just to the north of the platform end.

South of the station the line entered Sherwood Tunnel. This was curved, built on a gradient of 1 in 70 and 442 yards in length; it would have been 10 yards shorter had the farmer at Top Coppice Farm not insisted that it be lengthened to avoid disturbances of his yards.

From there, the line climbed on a gradient of 1 in 50 to St Ann’s Well Station. Its red brick buildings were similar in design to those at Sherwood but the platforms were longer and straight. Here the Up platform was of wooden construction giving it more of a temporary feel. The railway crossed Wells Road on a substantial skew bridge beside which was the passenger approach to the station. On the Down side was a small dock and the platforms were spanned by a wrought iron lattice bridge. The signal box stood at the north end of the Up platform but was taken out of regular use on 28th October 1904, thereafter being opened and operated by the stationmaster when required for dealing with traffic.

Departure from St Ann’s Well saw the line pass through Thorneywood Tunnel (408 yards) to emerge into a cutting beside Thorneywood Lane where Thorneywood Station was built. The east side of the cutting was strengthened by a massive blue brick retaining wall at its northern end. The platforms were straight and opposite each other; again, the buildings shared their design with Sherwood and St Ann’s Well. Approach to the station was from Marmion Road on the west side and a lattice girder bridge spanned the goods yard, linking Marmion Road with Thorneywood Lane. The booking office was on the Down side and a further lattice bridge connected the two platforms. The signal box was on the Up platform and there was a siding on each side of the main line.

Leaving Thorneywood Station the line passed beneath Carlton Road after which the short branch diverged to serve the brickworks. Just 154 yards south of the station, the line entered the 183-yard Sneinton Tunnel before crossing Sneinton Dale on an impressive three-arch blue brick viaduct. From here, on falling gradients, the line passed over the Midland Railway’s Nottingham-Newark line and the Great Northern route from Nottingham to Grantham before finally spanning Trent Lane and making its way along Great Northern metals to the London Road terminus.

Operational history, decline and closure

In 1890, there were ten trains a day running out of London Road along the line to Daybrook, four of which continued through to Newstead. In the opposite direction were nine trains of which four originated from Newstead. There was no Sunday service. The journey time from Nottingham to Daybrook was a very respectable 13 minutes. By 1895 there was a through train to Ilkeston which, on Fridays, was extended to Derby Friargate.

Unfortunately, within a little more than ten years, two developments occurred that would render the Nottingham Suburban Railway superfluous. The first was the arrival of the Great Central Railway which, in 1900, had opened up an even more direct route into Nottingham. Trains along the GC’s own Leen Valley railway could run directly from Newstead via Bulwell, New Basford and Carrington into Victoria Station, thus cutting out the lengthy negotiations of Daybrook Junction and Leen Valley Junction on the Great Northern route.

The second was the introduction of the electric tram. Horse-drawn trams had been operating in Nottingham since September 1878; however the arrival of the electric tram offered a quicker, more frequent service than the trains. The first route opened to Sherwood – running along Mansfield Road close to Sherwood Station – on 1st January 1901. Extensions to St Ann’s came on 21st February 1902, Thorneywood on 16th December 1910 and Daybrook on 1st January 1915. With their comparatively light loads and easy acceleration, the trams could negotiate the gradients in the hilly east of Nottingham more easily than steam locomotives. Indeed the clanging of the tram bell would, in the coming years, often sound the death knell for many a suburban railway station. The 1 in 49 gradient from Trent Lane Junction, which was also on a curve, posed particular problems for the GN’s Stirling 0-4-4 tanks which worked the line.

In order to achieve faster journey times than the trams, some of the suburban services were run non-stop from London Road to Daybrook. By 1914, whilst there were still eight trains a day each way along the line, only four of these stopped at the intermediate stations. For example, St Ann’s Well saw departures for Basford & Bulwell at 7.55am and, to Shirebrook, at 9.11am, 1.20pm and 4.58pm. In the opposite direction, trains departed for Nottingham at 8.24am, 2.21pm and 6.01pm. It is also worthy of note that other trains passed through the station at 11.38am, 8.40pm and 9.50pm en route to Shirebrook and to Nottingham at 10.36am, 12.59pm, 9.20pm and 10.41pm. Even before the closure of the intermediate stations – which at this time was less than two years away – more passenger trains passed through than stopped. One can only imagine the long deserted platforms at St Ann’s Well which, just a few years earlier, had anticipated unprecedented numbers of customers.

As a supposed wartime economy measure, the stations at Sherwood, St Ann’s Well and Thorneywood were closed to passenger traffic on 13th July 1916 and thereafter just two trains a day along the Leen Valley route used the line. After the war it became evident that the Great Northern had little interest in promoting services along the line nor reopening the intermediate stations. Bradshaw’s Railway Guide of July 1922 shows that, just prior to grouping, only three trains passed daily over the line.

On 25th January 1925 the collapse of Mapperley Tunnel on the Great Northern extension brought a brief flurry of activity for the Nottingham Suburban when all Leen Valley passenger and coal traffic was diverted over the line whilst repairs were affected.

Also, on 10th July 1928, their majesties King George V and Queen Mary opened the Royal Show at Wollaton Park and the new university buildings. Between these two events, their majesties reviewed a huge gathering of school children in Woodthorpe Park. As the nearest station was Sherwood, both Thorneywood and Sherwood stations were renovated and restaffed for the occasion. This made it possible for 6,550 of the 17,500 children and 284 of their teachers to be brought in on 13 special trains. It is ironic that, on that one day, the two stations saw more activity than they had ever done during their operational days.

The line was converted to single track with the removal of the Down line on 9th February 1930 when the signal box at Sherwood was closed and all signalling removed. The line was then worked by staff who unlocked the ground frames controlling the siding connections. Not long after, the footbridges and canopies were removed from the stations, a clear indication that they would never reopen. The last passenger train to use the line was the 5.05pm Nottingham Victoria to Shirebrook via Trent Lane Junction on 14th September 1931. Services had lasted just 41 years, with the intermediate stations faring even worse with an operational life of just 26½ years.

The next misfortune to befall the line occurred on the night of 8th May 1941 when, during Nottingham’s worst air raid of the Second World War, considerable damage was done in the Sneinton area. A bomb landed on the southern section of the line damaging a bridge over the Midland Railway and blowing away part of the embankment. This was never repaired and buffer stops were erected at either side, effectively creating two dead ends.

Subsequently the goods service along the line was reduced to a thrice weekly pick up, carrying domestic coal between Daybrook and Thorneywood only. But even this ended on 1st August 1951 thus bringing the story of the Nottingham Suburban Railway to an end. The last ever passenger train to run over the line had been a chartered enthusiasts’ special between Daybrook and Thorneywood on 16th June 1951. Apart from a short section at Daybrook, the tracks were lifted between June and October 1954. When the connection at Daybrook Junction was removed on 24th February 1957, the end of the line had truly come.

The route today

Today little evidence remains of the Nottingham Suburban Railway. Being situated in the city’s suburbs, both residential and industrial developments have obliterated most traces of it.

The site of Sherwood Station is now occupied by two blocks of flats known as Winchester Court. Their lock-up garages follow the curve of the former railway’s course, however the portals of Sherwood Tunnel are fenced off and hidden by dense vegetation.

The station house at St Ann’s Well remains, as do the abutments of the blue brick skew bridge over Wells Road. The cutting leading to Sherwood Tunnel was at one time used as a nature reserve by a local school.

Thorneywood’s station house still exists and the line’s course from there to Sneinton Tunnel has been made into a footpath. The latter’s portals have been partially obscured by infilling but access into the bore is still possible for members of the local gun club. Descending to Sneinton Dale, nothing remains of the three-arch viaduct which once took the line over it and the site is now occupied by a doctor’s surgery, medical centre and police station. The footpath resumes at a point just south of Sneinton and follows onwards to Colwick Road where the bridge has been removed. The girders of the bridge over the Midland Railway have gone; however the segmental arch and abutments at Trent Lane still exist.

Few people are now aware that the Nottingham Suburban Railway existed. The line which was built to serve early commuters has almost disappeared but one cannot help wonder whether it might have found a fruitful role today, when we are all being urged to ditch the car in favour of public transport. Could it have formed the basis of a regenerated public transport infrastructure in the city? We will never know.

© Simon Swain 2010

(Mick Garrett’s photo is used under this Creative Commons licence.)

November 2010

November 2010