Bennerley & Bulwell Railway

Bennerley & Bulwell Railway

The Midland Railway made an unsuccessful attempt to gain local traffic from the Ilkeston area with the construction of a branch from Ilkeston to Nottingham via Kimberley and Basford. Kimberley was one of a few small towns in Nottinghamshire that the Midland had neglected to provide with a passenger service. In the late 19th century, many small towns began petitioning the railway companies to provide them with stations – Kimberley was amongst them. When it became clear that the Great Northern Railway’s Derbyshire extension was to pass through the town, the 4,000 strong population did not hesitate in petitioning the Great Northern to provide them with a station. It complied and this was duly opened on 1st April 1878 with the other stations on the line.

As early as November 1871, the Midland Railway submitted plans to build a Bulwell to Bennerley railway. The line was approved on 25th July 1872 and authorised the following works:

“The Bennerley and Bulwell Railway of 5 mile and 40 chains, with a junction from the Erewash Valley at Ilkeston, 61 chains north of Ilkeston Junction and with a junction on the Nottingham and Mansfield Railway at Bulwell. The Watnall New Colliery branch of 1 mile 60 chains in the parish of Nuthall, junction with the Bennerley and Bulwell Railway in a field known as Narrow Sheeps Cribs and terminating in the parish of Greasley in a field known as gorse close.”

It was not until February 1875 that the Northern Construction Committee accepted a tender of £97,733 0s 3d from Mr T Oliver of Horsham to commence construction of the line. A tender had been submitted for construction as early as June 1873 however the Midland postponed the project, believing the cost to be excessive. The section from Basford Junction to Watnall Colliery opened to mineral traffic on 3rd December 1877 with the service consisting of one train each day, departing from Nottingham at 4pm to the colliery and returning to Beeston sidings.

Construction of the remaining section of line from Watnall Junction to Bennerley Junction proved more problematic, specifically the boring of the 151 yard long Watnall Tunnel – which did not appear on the original plans – and the construction of the embankment between Kimberley and Bennerley which required 12,333 cubic yards of material. By December 1877 420 men, 16 horses and eight stationary engines were at work on the line. These problems caused the Midland Railway to apply to parliament for an extension of time to build it. An act of 17th June 1878 allowed the company a further two years. This seems to have spurred construction onwards and it is reported that track laying started at Bennerley on 5th November 1878.

The line was eventually opened in its entirety on 12th August 1879 to goods and mineral through traffic. It was strategically located next to, or had connections to, six collieries in the area, these being Awsworth, Digby, Speedwell, New London, Watnall and Bulwell and, as such, coal was always the mainstay of freight traffic. Hardy and Hanson also had sidings serving their brewery on either side of the line at Kimberley.

Following the opening of the Derbyshire extension line, there was a realisation on the Midland’s part that, having failed to provide Kimberley with a passenger station, they were missing out on a lucrative share of the local passenger market. As we have already discovered, the area around Kimberley already had adequate passenger facilities provided by the Great Northern Railway. However, at a time when competition between railway companies was fierce, the Midland Railway saw the introduction of passenger services along the Bennerley and Bulwell branch as a means of recovering revenue lost to the Great Northern Railway. It was over three years after the line opened to goods traffic that passenger services commenced on 1st September 1882. The Derby Mercury of 4th September 1882 reported the following:

“The Bennerley and Bulwell branch of the Midland Railway, which has been for some years in the course of construction, has been opened for passenger traffic and the last of the railway extensions which the Midland Company propose to make in the Nottingham district at present was thus fully inaugurated.

“There was no attempt at a formal opening, the first train from Nottingham being dispatched at 12 minutes to eight and reaching Kimberley and Ilkeston in good time with a fair number of passengers. The ordinary passenger train service will consist of four trains each way per day and the principal advantage to be gained by the opening of the branch is to place Kimberley, which is a rapidly increasing manufacturing town, in direct communication with the Midland main line system. The line has been for some time opened for goods and mineral traffic and in that way has done much to lessen the growing demands which have been made for many years past upon the Erewash Valley branch. The termini of the new line are at present Nottingham in the east and Ilkeston town station in the west.”

When the branch had been opened from Watnall to Bennerley in 1879, a junction with the Erewash Valley main line had been constructed to enable through freight traffic to use the line. This junction now meant that passenger trains could travel from Kimberley via Bennerley Junction to the Midland’s Ilkeston Town Station. The opening of this latter route to Nottingham now meant that the Midland could offer passengers three routes into the city from Ilkeston – the first from Ilkeston Junction Station to Nottingham via Trent and Beeston; the second, also from Ilkeston Junction, ran via the Trowell and Radford cut off providing a quicker journey time; the third from its Ilkeston Town terminus took a route via Kimberley, Watnall and Basford. It can only be imagined that the Midland thought they were providing the best service between the two towns by offering a number of alternative routes. However we shall see that this saturation lead to the early demise of the Bennerley and Bulwell branch.

The route described

The Bennerley and Bulwell branch left the Erewash Valley main line at Bennerley Junction, just to the north of Bennerley Viaduct, and swung sharply in an easterly direction to pass the Bennerley ironworks and its associated sidings before proceeding – with the Gilt Brook running parallel to its course – to reach another junction where a branch to Awsworth Colliery veered away to the south-east. This line later passed beneath the Bennerley to Bulwell branch en route to Digby Colliery. After passing the Giltbrook chemical works, the line passed beneath the Great Northern Railway’s Giltbrook Viaduct. This impressive 43-arch structure took the Great Northern’s Pinxton branch over the line and the branch passed beneath the 15th arch on an embankment.

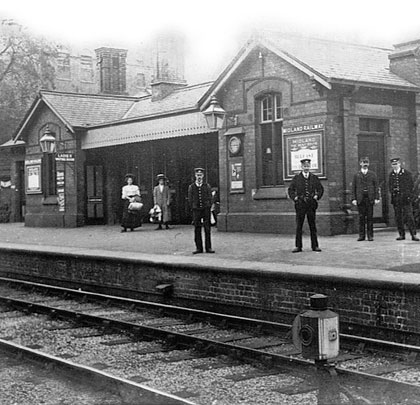

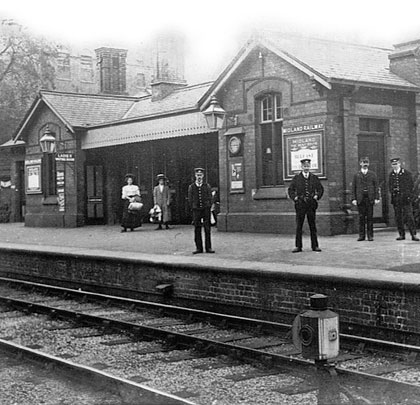

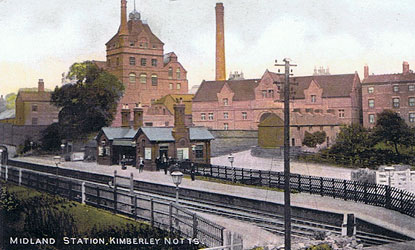

The railway proceeded in a north-easterly direction passing Speedwell Colliery to cross over Eastwood Road on a red brick and wrought iron deck bridge. Upon crossing Eastwood Road, the trackbed widened to accommodate the sidings and goods shed at Kimberley before entering the station itself. The station was opened to passenger traffic on 1st September 1882 and had been built at a cost of £2,495 15s 7d by Mr E Wood of Derby. The station has architectural significance as it was a representation of its architects, Charles Trubshaw, aspiration for station building design. Trubshaw’s predecessor John Crossley had advocated the gothic style of architecture; however by the time of Trubshaw’s appointment in 1878 a shift was taking place from the gothic style to the ‘arts and crafts’ movement – rustic sunflowers, terracotta and chimneys looking like cottages were in fashion. Charles Trubshaw adopted this style for what was probably his first project. Kimberley Station was built to a standard Midland design with notable embellishments in terracotta, including a large terracotta medallion at one end; it also had tall, ribbed chimneys.

Kimberley Midland was conceived and designed in a period of prosperity and optimism. However, the years 1883-1886 were economically lean ones. Trubshaw was deprived of funds and passenger stations on the newly opened Notts/Derbyshire coalfield lines became much plainer. By the early 1890s, the economy was on the up but fashion had changed and half-timbered buildings marked trends which were evolving away from Trubshaw’s original designs.

So, in the case of Kimberley, generous funding appears to have been available at the same time as the services of a keen young architect, eager to make his mark, and the arrival of a new and important style. This juxtaposition doesn’t seem the have happened again and, coupled with the destruction of most of its contemporaries, Kimberley Midland station appears to be a rare, and quite possibly unique, survivor.

The station was a simple affair consisting of two platforms built opposite each other. The buildings were located on the Ilkeston platform and consisted of booking hall, waiting rooms and ladies and gentlemen’s toilet facilities. There was no footbridge at Kimberley and access between the platforms was by wooden board crossings located at both ends of the platforms. The goods depot and cattle dock were located at the end of the Ilkeston-bound platform. Access to these facilities and the station buildings was obtained by a driveway which descended steeply from Hardy Street.

The station at Kimberley was built within the shadow of the impressive buildings of Hardy and Hanson’s brewery. The brewery had opened in 1847 and was one of the country’s last independent breweries when it ceased production in 2006. Beyond the eastern end of the platforms, a red brick arch bridge took Hardy Street over the railway. Beyond this, the main lines ran with the sidings to Hardy and Hansons breweries running on either side. Both sidings rose to the breweries on steep gradients and that serving Hardys breweries entered the brewery which necessitated a level crossing on Hardy Street. As Midland locomotives were not allowed to cross the street, wagons for the brewery were pushed up the siding and across the road before being taken forward by the brewery company’s locomotives.

The line from Kimberley ran in a 52-foot deep sandstone cutting for half-a-mile before reaching the western end of the 151-yard Watnall Tunnel. The tunnel bored its way beneath the main Nottingham to Alfreton road and, upon emerging, it was only a short distance from the eastern portal to the station at Watnall.

Watnall Station was in another deep cutting and the buildings had a similar design to those at Kimberley, having also been designed by Charles Trubshaw. The buildings were built in stone but involved a new outline with lower pitched roofs, as opposed to previous station designs which favoured steep gables The station boasted two platforms which were built opposite each other. The Down platform was built into the cutting and therefore was faced with exposed sandstone. The buildings were located on the Up platform and comprised of a booking office, waiting room, Station Master’s office and toilet facilities. There was also a wooden waiting room on the Down platform. Access to the station was from a steep driveway which ran down to the station from the Alfreton to Nottingham road, continuing past the station frontage to end at the western end of the goods yard. There was no footbridge connecting the two platforms and access to the Down platform, for Ilkeston-bound services, was by two wooden sleeper foot crossings at either end of the Up platform. The goods shed was situated on the Up side and was connected to the main running lines. Trains coming from the Basford direction were able to cross over the Up line and hence gain access to the sidings and goods shed.

Just to the east of the station, the line was spanned by a wooden bridge with limestone support pillars. This bridge carried the private colliery lines of the Barber-Walker Company. This branch had its main line connection with the Great Northern Railway at Nuthall Sidings where from it ran to cross the Midland at Watnall Station before proceeding to cross the Midland’s own branch to Watnall Colliery. The Barber-Walker Company owned and had interest in several collieries in the area and built a comprehensive rail network to link them.

The line continued within the confines of its sandstone cutting before emerging just to the west of Watnall Junction which was where the Midlands branch from Watnall Colliery joined the Midland line. Coal workings from the colliery would travel via Watnall Junction and along the Bennerley to Bulwell line to Basford Junction and, from there, either to Nottingham or beyond or northwards up the Leen Valley.

From Watnall Junction, the industries of Bulwell and the lower Leen Valley would have been afforded as the railway continued across open farmland before being spanned by a bridge constructed of Bulwell stone with an iron deck. This carried a farm track which linked adjacent farmsteads. Mention is made of this otherwise nondescript bridge as it remains today, still serving its original purpose against the backdrop of the M1. In its isolated location next to one of Britain’s principal motorways, the little 0-4-4 tanks with their rakes of teak clerestory coaches seem a far cry away from here.

The railway then ran across more open farmland on a shallow embankment before again crossing another track on a Bulwell stone bridge. When the line was constructed, there were two quarries located on either side of the line; however, by 1885, local maps show that both were disused.

From here, the line passed to the south-west of Sellers Wood and began to turn, heading in a south-easterly direction. A loading platform and sidings were constructed sometime between 1885 and 1900; this presumably enabled coal, which had been brought by a tramway from Bulwell Colliery, to be loaded into wagons and transported further a field. From this point, the railway was on an embankment and running through an area of heavy industry interspersed with residential streets. Potteries, brickworks, bleach works and clay pits were among the industries alongside the line before it crossed Coventry Road and the River Leen on a three-span stone and iron deck bridge. This was the largest and most impressive on the whole line.

After crossing the river, the line ran parallel to the Midland’s Nottingham to Mansfield Leen Valley line for a distance before it was crossed again by the Great Northern’s Derbyshire extension. At Basford Junction, the Bennerley and Bulwell branch ran into the Nottingham-Mansfield line on a trailing junction whilst another Midland branch headed in an easterly direction to serve Cinderhill Colliery. From here, the Bennerley-Bulwell services would have used the same metals as the Leen Valley trains to Radford and Lenton stations before joining the Midland’s Nottingham to Trent line at Lenton North Junction and into Nottingham Midland Station.

An operational history

When passenger services along the Bennerley and Bulwell branch commenced in September 1882, the Midland Railway operated six trains daily along the line in each direction. In the years prior to 1900, additional trains were run on Wednesdays and Saturdays only to enable passengers to travel to markets in neighbouring towns. These usually consisted of additional trains from Nottingham at lunchtime and in the evening, with just one service from Ilkeston back to Nottingham in the evenings.

From Nottingham Midland, trains would travel via Lenton and Radford to join the branch at Basford Junction before continuing to Watnall, Kimberley and Ilkeston. Throughout the short passenger life of the line, trains were run from Ilkeston onto other destinations such as Pye Bridge, Ambergate, Butterley via Langley Mill and Heanor as well as Mansfield, Chesterfield and Sheffield. These were presumably for the benefit of passengers from Watnall and Kimberley who would otherwise have been unable to make the through journeys to these destinations without changing at Ilkeston.

It soon becomes apparent that during the early years of passenger carriage along the line, considerable effort was made by the Midland Railway to generate passenger revenue. It could also be argued that the fact that through trains were provided from Kimberley and Watnall to destinations that would previously have been difficult to access by rail was to compensate for the fact that they had originally failed to provide services to these communities and, by doing this, could regain passenger revenue that it had lost to its rival the Great Northern.

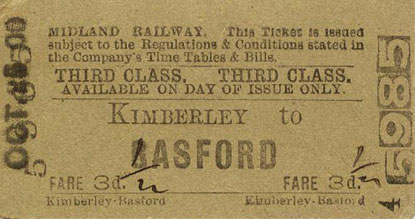

However, despite the best efforts of the Midland, passenger traffic never developed as anticipated and its services never came close to seriously rivaling those provided by the Great Northern. But why should this be so? Firstly, one has to consider the route taken by each company from Ilkeston to Nottingham. Despite the Midland being the first company to arrive in the Erewash Valley, it is arguably that the Great Northern had the better route. As has been previously mentioned, in 1910 it was possible to make the journey from Ilkeston to Nottingham on the Great Northern in just 15 minutes. This was on a route which provided passenger services at Awsworth, Kimberley and Basford & Bulwell. On the other hand, the Midland – with just the Bennerley and Bulwell branch taking 36 minutes – offered a journey lasting more than double the time taken by Great Northern services. This was on a route which provided passenger services at Kimberley, Watnall, Basford, Radford and Lenton. Even if we consider the Midland’s other alternative routes to Nottingham via Trent and via the Trowell & Radford cut off, they could still only manage the journey from Ilkeston to Nottingham in 22 minutes in 1910.

The second point for consideration is those towns that both railways served. Nowadays one would expect that two different routes between the same destinations would encompass different centres of population. In the case of the Bennerley and Bulwell branch, the problem was that it didn’t serve any areas of population that didn’t already have adequate passenger provision from the Great Northern Railway. If we exclude the stations on the Leen Valley section of the line from Nottingham, the only place not served by the Great Northern was Watnall.

Thirdly, we need to consider the location of the railway stations in relation to the centres of population which they served. Having arrived in the area first, the Great Northern chose a location at Kimberley which was pretty central to the town. The Midland’s station was to the west of the town, further away from the town centre. This would not have been a particular problem when the railways first arrived as people would not consider a walk of up to three miles to reach a railway station an inconvenience. It was only when the electric tramcar and motorbus became established and people could be taken closer to their destination that passenger revenues really began to suffer.

Returning to our example of Kimberley, whereas both stations were located within half-a-mile of each other, the Great Northern was at an immediate advantage as it had arrived in the town first and secured a majority of the passenger traffic; secondly, as we have previously discussed, its services ran more frequently and its station was more central to the town. In hindsight, passengers were not given any real incentive to use the Midland’s facilities and it is hardly surprising that the potential for this line was never realised.

Whereas the Midland probably resigned itself to the fact that, as a passenger concern, the branch was never going to be viable, it hoped that the freight traffic it generated would see the line develop as a main pick-up thoroughfare between two of its more successful lines, the Erewash Valley and Leen Valley railways. Indeed we must not forget that the conception and construction of the line had been driven by developing industry. It had been the Midland Railway’s aim that the line should deal with traffic from connections to colliery yards and ironworks at Watnall and Bennerley, Watnall brickworks, the brewery at Kimberley and the lime kilns on the north-west outskirts of Bulwell. However, as with passenger traffic, the anticipated through freight didn’t materialise as expected with a majority of it being localised.

(Timetable courtesy of the Midland Railway Society)

The passenger and working timetable information for July 1898 demonstrates this point well, showing that passenger trains departed Nottingham Midland for Kimberley and Ilkeston at 0638, 0755, 0855, 1045, 1315, 1522 and 1825. There was also an additional train which ran on Saturdays only, departing Nottingham at 2105. In the other direction, trains departed Ilkeston Town for Nottingham at 0903, 1055, 1340, 1500, 1740 and 2053. Again there were additional services, these being a departure on Mondays only at 0750 which started at Kimberley and a Saturdays-only train leaving Ilkeston Town for Nottingham at 1305. The passenger timetable shows that many of these trains were run through to Ambergate, presumably to connect with Midland main line services to the north. Some services also ran through to Pye Bridge for connections to Butterley, Ripley and Heanor, whereas others continued to Mansfield.

The working timetable, corresponding with the same period, shows that there were approximately four trains each day to and from Watnall Colliery, with some services continuing to pick up freight from Kimberley and Watnall stations. The nature of this traffic was, on the whole, localised with trains either originating from or traveling to local collieries and marshalling yards, presumably for onward transportation.

(Timetable courtesy of the Midland Railway Society)

Decline and closure

For nearly 30 years, the Midland Railway operated a standard service of six trains daily along the branch with timetables throughout this period showing only slight variations in running times. However, by the end of the Edwardian period, developments in public transport were beginning to have a significant effect. On 23rd July 1901, Nottingham Corporation Tramways began operating tramcars from Nottingham city centre to Bulwell and, by 21st October 1901, tram tracks had been laid to the Midland station in Nottingham, thus enabling the public to travel direct from the station to Bulwell. This was followed on 30th September 1902 by the start of services to Lenton.

The effect that the tramways had upon passenger services on the Bennerley to Bulwell branch must have been disastrous. They operated at a frequency of six minutes during the day and at three minute intervals during peak times. As we have mentioned earlier, they were also able to take people closer to their destinations than the trains ever could and, additionally, they were cheaper. The railways simply could not compete and economies in services resulted.

The Midland’s first casualty was the closure of Lenton Station on 1st July 1911. Whereas it can be argued that Lenton Station was not on the Bennerley and Bulwell branch, it does demonstrate well that even on highly successful lines such as the Midland’s Leen Valley, passenger patronage could not be guaranteed even prior to the First World War. Bearing this in mind, it is hardly surprising that passenger service provision at the stations on the Bennerley and Bulwell branch suffered a similar fate a little over five years later.

The outbreak of World War One on 4th August 1914 hit the railways hard nationally. From July 1915, services along the Bennerley-Bulwell were cut to just five trains in each direction daily; however, in a further attempt to economise, services were speeded up and the last train of the day did not call at Watnall. This was presumably a final attempt to compete with the Great Northern Railway services. Although the July 1916 timetable maintained the same level of service as the preceding year, trains were timetabled in such a way that it would be exceptionally difficult for any substantial journeys to be made. For example, from Nottingham there was a gap of 3½ hours from 1003 to 1330 for Ilkeston-bound services. From Ilkeston, the provision was worse still with a gap of 5½ hours between 1255 and 1830 for Nottingham-bound trains. It is little wonder that the line was to become a casualty of wartime economy measures.

On 27th December 1916, the Derby Mercury newspaper reported that from 1st January 1917 drastic reductions and closures of branch lines would occur. The Midland Railway lines in Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire were heavily hit. The passenger service between Ilkeston and Nottingham via Kimberley was withdrawn on 1st January 1917 as the area had an alternative service provided by the Great Northern. Therefore, at 1045pm on Saturday 30th December 1916, the last passenger train departed Ilkeston Town Station for Nottingham via Kimberley, thus bringing to an end just 34 years of passenger services along the line. It has been alleged that in 1917, after passenger services had ceased, that the rails of the branch were lifted and transported to the Dardanelles to assist the war effort. Furthermore, it is stated that the rails never reached their destination as the ship on which they were being carried was torpedoed and sunk. However, the author has been unable to find any documentary evidence to substantiate this claim.

Through freight traffic continued to use the line until they to were withdrawn in 1921. That year, the Midland Railway traffic committee met to discuss whether to reintroduce the passenger service between Nottingham and Ilkeston Town via Kimberley. It was decided that the company could save £8,444 per annum if the passenger service wasn’t reintroduced. In November 1923, the route between Bennerley and Basford junctions was reduced to a single line and severed to the west of Kimberley at Digby Colliery Junction. This, in effect, created two separate lines with the short section between them being lifted. The branch from Bennerley Junction was retained to serve Bennerley Colliery and the ironworks whilst the western section from Basford Junction to Kimberley remained in use for Watnall Colliery and the brewery at Kimberley. This eastern section was operated by staff from Basford Junction to Watnall Colliery. An Annett’s key was used between Watnall Junction and Kimberley with the points being set for traffic towards Watnall Colliery.

In 1938, the site of Watnall Station was acquired by the RAF and construction began on a filter block, bunker and communications centre for 12 Group, Fighter Command HQ – an operation which was completed in 1943. As a result of this acquisition, it was necessary to demolish the station buildings and platforms at Watnall Station. However, a narrow strip of the Down platform was retained for military traffic.

During the interwar years, the remaining freight traffic on the line gradually began to dwindle away and this was compounded by the closure of Digby and New London collieries on 5th November 1937. With the brewery at Kimberley preferring to use road transport, another large proportion of the line’s traffic was lost. As a result, British Railways closed Kimberley Station to goods traffic on 1st January 1951. Watnall Station fared little better and the eventual transfer of any remaining traffic to the roads meant that there was no need to retain a freight service along the branch; the station was closed on 1st February 1954.

Following closure, the eastern section of the line became derelict. During 1955 and continuing into 1956, the eastern section of the line from Kimberley to Basford Junction was lifted and the occupation bridges along the length of the route removed. By far the most significant bridge on the line, with the exception of the Coventry Road over bridge in Bulwell, took the line over Eastwood Road in Kimberley. Following track lifting work and bridge removal, this section of the line was abandoned and reverted to nature.

The western section of the branch fared slightly better. When Bennerley ironworks was closed in 1962, the land was bought by the National Coal Board which proceeded to erect a coal screening plant on the site. Between the closure of the ironworks and the construction of the screening plant, the branch had been used by British Railways to store old wagons prior to breaking up. The NCB retained the rail connection at the screening plant and this was used to transport the large volumes of coal obtained as a result of extensive opencast workings during the 1970s and 1980s.

The route today

Today, there still remain traces of the branch. However, as with many abandoned railways, modern developments have obliterated their course in some parts. Bennerley Junction and the sidings which served the former Bennerley coal screening plant remain, albeit now disused. They follow the course of the original alignment and the track here remains in situ, albeit overgrown and with sections missing. Looking back towards Bennerley Junction from this vantage point, Bennerley Viaduct forms the backdrop and it would be hard to guess from the wasteland left after the removal of the screening plant that, less than a hundred years ago, the area was dominated by heavy industry. A recent inspection revealed that the crossover from the main line to the branch, which still existed as late as 2007, has now been removed.

From Bennerley sidings, the discerning eye can still trace the alignment of the railway as it headed towards Kimberley. The course abruptly ends where it is dissected by the old road which once led to the coal screening plant. The Ripley-Nottingham road and an Ikea superstore have obliterated any remains of the railway until a point just east of where it would have passed beneath Giltbrook Viaduct. Until the viaduct was demolished in March 1973, the densely overgrown embankment remained at this site. From here to Eastwood Road in Kimberley, sections of the embankment remain although it goes without saying that the junction for Awsworth and Digby collieries has long since disappeared.

The red brick eastern abutment of the bridge which carried the line over Eastwood Road still remains, however the western abutment and iron deck were demolished in November 1955. Beyond the Eastwood Road bridge, it is now impossible to distinguish the course the line to Kimberley Station due to landscaping of the embankment and the growth of trees which have overtaken the site since the track was lifted.

At Kimberley, the station buildings survive despite not being used for over 90 years. When it closed, the buildings and yard to the west of the station were bought by the Hardy and Hanson brewery which, until the 1990s, used the building as a social club. During that time, a number of ill-matching additions were made. At present, the building is not in use, taking on a forlorn appearance with the original roof slates missing and loss of most of the original chimney stacks. It has also become a target for local vandals who have forced entry and lit small fires as well as decorating the exterior with graffiti. Traces of the buildings’ former glory do remain with the survival of the ornate floral brickwork and decorative lintels. The station approach is extant and, despite being purchased by the brewery, the site of the goods yard has not been developed. Its expanse gives an indication of the size of the goods facilities provided here. Unfortunately all traces of the platforms have been removed and the trackbed cannot be accessed here due to the encroachment of dense vegetation. Either side of the Brewery Street bridge, the cutting has been filled in so that today only the parapets remain. Looking in the direction of Watnall, it is though still possible to see the brewery platform and the course of the railway as it went deeper into the cutting.

Kimberley cutting has been designated a site of special scientific interest and this status means that, for now at least, this section of the trackbed is protected against development. The three-arched brick bridge which once provided access to the brewery still remains and today is used by pedestrians to access housing estates that have been built on both sides of the cutting. The conservation of the site also means that the true depth of the cutting can be appreciated – one can only imagine the amount of rock and earth which had to be removed to create this impressive engineering feature.

It is not possible to follow the trackbed to the western portal of the 151-yard Watnall Tunnel due to vegetation and waterlogging. In the late 1990s, a new development of luxury homes was built at the top of the cutting’s north side and it is probably safe to assume that the earth removed during their construction probably ended up in the cutting, thus obscuring the tunnel mouth. However, it is still possible to obtain a glimpse of the eastern portal – with its distinctive Bulwell stone copings – by taking a lane off the main Alfreton to Nottingham road. It has been filled in and silver birch trees now grow on the infill.

The station approach exists at Watnall; however, unlike at Kimberley, no trace remains of the station buildings. Together with the platforms, they were demolished in the late 1930s to facilitate the construction of the RAF command centre. Various parts of the derelict RAF bunker remain but the section of original platform retained for military traffic has not survived. It is difficult to imagine that a railway once ran through here as the trackbed is densely overgrown and extremely waterlogged, and the scant remains of the sandstone cutting in which the station was built are the only reminders which betray the site’s former user. The bridge and its limestone abutments which carried the private railway of Messrs Barber and Walker have long since disappeared and the establishment of an industrial estate on Common Lane has served to destroy the area’s previous industrial use.

From this site, the railway ran in a deep cutting which was bored through the Permian sandstone of the area and, as at Kimberley, this site is also protected. A path runs parallel to the cutting, leading eventually to the site of Watnall Junction. However, occasional glimpses of the cutting below give a good indication of its depth and parts of its exposed sandstone can also be seen. Watnall Junction was where the private Barber-Walker line from Watnall Colliery joined the branch line. Watnall Colliery was just one of many served by the company and its lines were connected to both the Midland and Great Northern railways at Langley Mill. Today, the course of the line can be seen curving in from the north-west but the actual junction site is densely overgrown with just a minor footpath through woodland passing close by its site. The course of the line continues through farmland until the M1 is reached. Here, as has been previously mentioned, an iron-decked bridge remains with its Bulwell stone abutments. Standing next to the motorway, the bridge has a stranded appearance and its survival is questioned until one discovers that the track which is carried across it is retained for access to nearby farms. From the top of this bridge, views of the course of the line beyond the M1 can be afforded and a wooded embankment, which curves to the south-east, shows where the railway would once have run.

It is possible to take the track from the Bennerley and Bulwell over bridge, over the M1 and walk to New Farm where the alignment of the railway can be regained. A section of the embankment remains in the fields but the railway from here back to the M1 has been reclaimed for agriculture. A footpath leads alongside the embankment where, after a short distance, the Bulwell stone abutment of an over bridge is found. It is possible to gain access to the trackbed by negotiating the side of the bridge and retracing the line’s course as it passed through Sellers Wood.

After approximately half-a-mile, the trackbed ends abruptly and here it is necessary to descend to road level again, following the approximate course of the railway as it entered Bulwell. The road is built on its own small embankment and minor roads off Sellers Wood Drive, such as Bennerley Drive and Pottery Way, make subtle references to the name of the line and the industry which grew up around it. Sellers Wood Drive eventually terminates at a junction with Coventry Road and Main Street in Bulwell and the site of this junction marks the approximate point where the railway would have crossed over Coventry Road. This bridge was demolished in the 1960s and a development of flats and various other buildings mean that no traces remain. The bridge would have taken the line over the River Leen before running parallel to the Mansfield-Nottingham line, just south of Bulwell Station. The section of trackbed where the line ran to Basford Junction remained and is used by the Nottingham express transit trams. Basford Junction also survives and, here, Phoenix Park-bound trams use the trackbed of the Midland Railway’s Cinderhill Colliery branch.

The Bennerley and Bulwell branch of the Midland Railway is probably one of the least documented of the Erewash Valley lines. Why should this be so? Despite it generally being relegated to a couple of pages in most railway publications, it certainly deserves more attention as it serves as one of the best testimonies of the rivalry that emerged between the Midland and Great Northern railways. Had the Great Northern not entered the Erewash Valley with its Derbyshire extension line then the branch would almost certainly have remained a minor goods branch. However, in the late 1870s, passenger markets were a lucrative business and the decision to introduce passenger services along the line was a gamble that the Midland made which unfortunately didn’t pay off. However, we cannot dismiss the fact that the line was open for 75 years handling freight traffic and, despite not developing as anticipated, it did generate revenue for the company in the locality. Whilst not being one of the Midland’s greatest success stories, it certainly does not deserve obscurity.

© Simon Swain 2009

Sources

The Midland Railway around Nottinghamshire: Volume 1 (Geoffrey Hurst)

Lost Railways of Nottinghamshire: (Geoffrey Kingscott)

The Rise & Fall of Nottingham’s Railway Network: Volume 2 (Hayden J Reed)

A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 9 – The East Midlands (Robin Leleux)

The British Library

November 2009

November 2009