The story of Ingleton Viaduct: The North-West Frontier

The story of Ingleton Viaduct: The North-West Frontier

Today’s much-maligned railway is beset by complication, not least thanks to its vast array of component parts. Coordinating the entangled mass of operators, regulators, contractors and consultants is a costly business and the quest for consensus can induce paralysis. Inevitably, passengers pay the price – both literally and metaphorically.

Viewed through rose-tinted spectacles, the railway of yesteryear was devoid of such failings. Yet we forget that our integrated network was once a disjointed mishmash of lines, owned by dozens of companies with shareholders to placate. In a climate of cut-throat competition, any opportunity to scupper a rival would be grasped with both hands after the passenger’s needs had been thrown from the window.

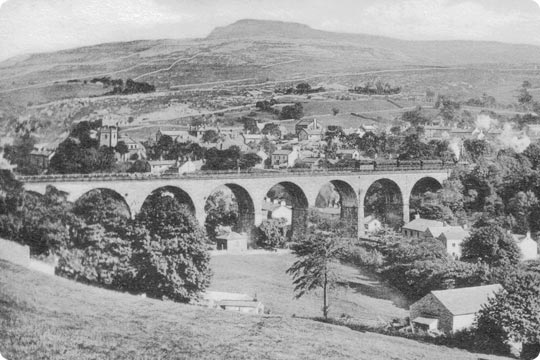

One such conflict spoilt the party in the northern Pennine hills. Battlelines were drawn between the ruthless giant of the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) and its challenger, the ambitious Midland. Each operated a station at Ingleton, either side of the valley, with a sandstone viaduct of 11 arches spanning the divide between them. It carried the contentious route from Clapham to Lowgill 80 feet over the River Greta. Built as an express link between the West Riding and Scotland, the line spent a hundred years as a quiet rural backwater, its relegation caused by corporate squabbling. The story of the Ingleton Branch is one of unrealised potential.

In February 1845, the North Western Railway Company issued a prospectus for four sections of new line, connecting the Leeds and Bradford Railway’s extension at Skipton with the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway. The plans, drawn up by Charles Vignoles and Robert Stephenson, featured a branch to a northerly junction near Lowgill, thus creating the shortest route from London to Scotland.

Two of the proposals had been jettisoned by the time Royal Assent was granted in June 1846. The branch was now the main line. Its first sod was cut six months later and construction work soon began at Ingleton.

But the chill wind of financial frugality was beginning to blow. Daunting engineering requirements at the northern end of the line threatened to suck £350,000 from the company’s coffers so attention was refocused on the simpler second scheme, from a junction at Clapham (yes, there was another Clapham Junction) to Lancaster.

The foundations of the viaduct – complete but redundant – stretched out beyond the buffer stops at Ingleton’s single line terminus. The first passengers arrived from Skipton on 30th July 1849 but, within a year, the Lancaster spur opened and the Clapham-Ingleton section was abandoned – probably the shortest-lived train service in railway history!

Despite its strategic significance, the missing link to Lowgill valiantly withstood all efforts to resurrect it. Five companies played roles in a complex plot of dithering and brinkmanship until, in June 1857, a Commons Committee accepted proposals from the Lancaster and Carlisle. The builders moved in during the summer of 1858.

Colour photos: Four by Three

Trackbed, structures and earthworks consumed the Lune Valley as 1,600 navvies pieced the route together with characteristic Victorian courage. Its 19-miles were split into four contractual sections, three of which encompassed substantial viaducts – Lowgill, Lune and Ingleton, the latter being the longest at 800 feet. Forty men were engaged to build it and did so, without loss of life or broken limb, in just two years. The line’s resident engineer had the honour of fixing the final keystone in place.

Ordered progress on the ground was set against a background of upheaval in the boardroom. The Lancaster and Carlisle Railway, including the Ingleton Branch, was leased to the all-conquering LNWR. Meantime, the North Western Railway had been swallowed up by the Midland which set about doubling the single line into Ingleton, anticipating completion of the new link through to Scotland. Trouble was these two giants held a mutual animosity, as the Midland had got into bed with the Great Northern Railway – the LNWR’s leading competitor – to gain access into London.

Ingleton was reborn, but found itself on the frontline when its inaugural train pulled in on Monday 16th September 1861. Unable to reach agreement for shared use of the Midland station, the LNWR opened their own at the northern end of the viaduct, about a mile out of town. Thus passengers were confronted by a strenuous hike when changing trains, particularly if burdened by luggage.

Services on the branch were slow – taking an hour from one end to the other – and the LNWR deliberately mistimed its trains to ensure poor connections with the Midland. The promised through services didn’t materialise.

These antics infuriated both passengers and operators alike. With complaints mounting, the Midland contemplated a retreat from the Ingleton Branch to engineer its own route through to Carlisle. Faced with the prospect of competition for its Scottish traffic, the LNWR was immediately overwhelmed by common sense and sought a cooperative future. The rivals spent months at the negotiating table but, on the brink of an accord, the Midland withdrew in a dispute over rights at Carlisle.

In August 1865, planning got underway on its independent line from Settle, navigating a stormy Parliamentary passage to receive Royal Assent a year later. Undeterred, the LNWR made more conciliatory noises and a deal was finally done to allow the Midland running powers over its route north. But the politicians were unimpressed and rejected Midland’s application to abandon the Settle-Carlisle scheme. For the Ingleton Branch, this effectively killed off any lingering aspirations of main line status.

With its future clear, the frosty relationship between the competing companies began to thaw a little. LNWR’s trains were soon running through to Ingleton’s Midland station although the continued operation of two halts in the town proved bewildering for some passengers, uncertain where to board their train. For a penny, trippers could take a ride between the two and enjoy the vista from the viaduct.

The line had settled into a cosy routine when Britain’s railways were reorganised in 1923, thrusting the LNWR and Midland together and, for the first time, uniting the branch. Ingleton’s ‘other’ station disappeared from the timetable and was eventually demolished.

In spite of its chequered history, the railway was woven into the fabric of local life, not just as a community servant but also an employer. One of those welcomed into the family was Albert Oversby, whose career path brought him to Ingleton in March 1951, tending the permanent way with a ganger and fellow trackman. Their ‘length’ stretched two-and-a-quarter miles from the southern end of the viaduct, through the station and back towards Clapham.

Hard work held no fear for Albert, which was just as well because there was always a job to be done. “The ganger had been on the railway a long time and was pretty easy going” recounts Albert. “He didn’t worry a lot. But the other chap was more conscientious.”

The track didn’t take much looking after, there being so few trains. So, whilst the ganger was walking the length to check the bolts and keys, Albert and his mate would do the housekeeping – weeding, ‘hedge slashing’ and cutting back vegetation on the embankments. “We had to oil the points every week – if they got really dry, the levers were hard to pull and the signalman got stroppy! I just wanted to keep things so the trains kept running without too much trouble. I wasn’t interested in making the ballast look tidy! But the Chief Engineer and the Chief Inspector walked through every length once a year and the best one got a prize. We never won. I didn’t want to work on a prize length – the ganger was usually so obsessed with it!”

It was a happy existence though the Pennine weather often let the side down. “When it was bad, we’d sit in the cabin because it wasn’t really safe to be out. We had plenty of coal for the fire.” With 60 mph trains rattling past, life on the line had its dangers. “We’d no lookout men then because there were just three of us – you couldn’t spare one. So you always thought to look out in case a train was coming. You could hear them if it was a quiet day but not if it was windy. The drivers were very good – they’d give you a whistle but you couldn’t always rely on that.”

Indeed you couldn’t. Gangers proved particularly vulnerable – working alone, busying themselves inspecting the track. Four were killed on local lines including one who was hit by a train in a snowstorm. There was safety in numbers. Sometimes three gangs would come together – usually on a Thursday – if a section of track needed slewing. “And if we went onto another length we got what they called ‘basket money’ – one-and-tuppence a day” Albert recalls with some relish.

During wet shifts or at lunchtime he would go and sit with the signalman. “I played dominos with him and got to learn quite a bit about signalling.” Albert took a job as porter-signalman at Kirkby Lonsdale but six months later a post became vacant back at Ingleton box. “When I took it I knew the line would be closing because we’d all heard rumours.”

As rail traffic haemorrhaged, the economic axe began to fall on lines across the network and Ingleton lost its passenger service on 30th January 1954. Albert was on the late shift. “I saw the last train go out with the Kirkby Lonsdale Brass Band on and all the local dignitaries. It was quite a do. There were more people on that train than they’d ever been before!”

Freight continued on the branch and, for three months, Albert remained at Ingleton as porter-signalman, handling parcels and goods. He then took a signalman’s post at Eldroth but eventually returned to the permanent way, seeing out his working days as Track Chargeman at Lancaster before retiring in 1988.

Excursion trains continued to visit Ingleton on Sundays and Bank Holidays, whilst specials were laid on at holiday time to collect pupils from nearby boarding schools. The ultimate irony came during the winter of 1963 when the Settle-Carlisle succumbed to severe snow for several weeks and main line traffic was diverted along the branch, finally fulfilling the role for which it was built. But this minor triumph did little to justify the continued expense of maintenance. The coffin lid was eventually shut in 1967 and, before the year was out, the track had been lifted.

It didn’t take long for the creeping blight of neglect to set in. Ingleton station fell derelict but the site has since been transformed into a car park and Tourist Information Centre. Other stations were converted into homes. The imposing arch of an iron bridge over the River Rawthey near Sedbergh now carries a pipeline on behalf of the gas board but most impressive of all are the railway’s three listed viaducts. These grand structures still dominate their landscapes and survive as memorials to the main line that never was.

More Information

| Leeds-Lancaster-Morecambe Railway | The history of lines in the area. |

| British History Online | The history of North Westmorland railways |

| Out of Obvilion | A Landscape Through Time – Canals and Railways |

| The Settle-Carlisle Railway | A brief history of the line. |