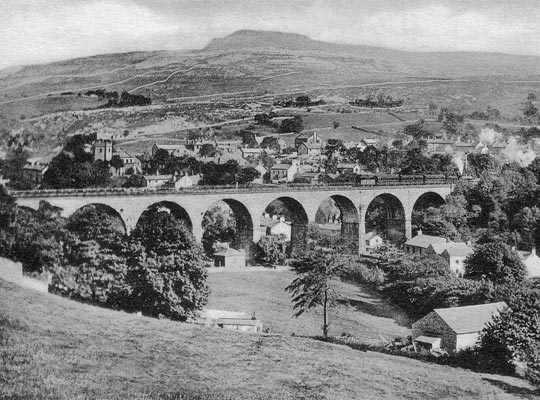

Ingleton Viaduct

Ingleton Viaduct

In February 1845, the North Western Railway issued its prospectus for four sections of new line, connecting the Leeds & Bradford Railway’s extension at Skipton to the Lancaster & Carlisle. Drawn up by Charles Vignoles and Robert Stephenson, the plans included a branch heading north to Lowgill on the L&C, thus establishing the shortest route from London to Scotland.

Two of the proposals had been dropped by the time Royal Assent was granted in June 1846: the branch was now the main line. Six months later, the first sod was cut and construction work soon began on a substantial viaduct at Ingleton. However, daunting engineering requirements at the other end of the line threatened to cost the company £350,000 so attention was refocused on the easier scheme, from a junction at Clapham to Lancaster.

The viaduct’s foundations – complete but redundant – stretched out beyond the buffer stops at Ingleton’s single-line terminus when the first passengers arrived there from Skipton on 30th July 1849. However, within a year, the Lancaster spur had opened and services over the Clapham-Ingleton section were withdrawn.

Despite its strategic significance, the missing link to Lowgill withstood all efforts to resurrect it. Five companies played roles in a complex plot of dithering and brinkmanship until, in June 1857, a Commons Committee accepted proposals from the Lancaster & Carlisle. Work got underway over the summer of 1858, the 19-mile route being split into four contractual sections, three of which encompassed substantial viaducts – Lowgill, Lune and Ingleton

The latter extends for 265 yards, comprising 11 brick arches each 57 feet in span and springing off dressed stone imposts. The tracks were carried at a height of 85 feet above the River Greta. The contractor, James Taylor, engaged 40 men to build it using white sandstone from a quarry near Bentham; they did so – without loss of life or broken limb – in less than two years. It must of course be recognised that the foundations were already in place from the aborted NWR scheme. Donald Campbell, the line’s resident engineer, had the honour of placing the final keystone on 8th May 1860.

The parapets comprise rows of rubble-faced stone topped with railings. Immediately below are half-round oversails; on the viaduct’s south side, this is interrupted by the timber support for a signal post which controlled trains approaching the L&NWR station beyond the west end. Water is drained from the deck by means of pans and pipes fitted to the piers; these bear the date 1860. Modest cutwaters prevent erosion of the pier standing in the river.

At the eastern end of the viaduct – between it and the Midland station – the line was carried over Bank Top by an iron girder span with brick jack arches.

The Lancaster & Carlisle Railway, including the Ingleton Branch, was leased to the all-conquering London & North Western Railway in 1859. Meantime, the NWR had been consumed by the Midland which set about doubling the single line into Ingleton, anticipating completion of the new link through to Scotland. However these two giants held a mutual animosity as the Midland had got into bed with the Great Northern Railway – the L&NWR’s leading competitor – to gain access into London.

Ingleton was back on the timetable, but found itself ill-served by the two companies when its passenger service restarted on Monday 16th September 1861. Unable to reach agreement for shared use of the Midland station, the L&NWR had opened its own at the other end of the viaduct. Thus passengers were confronted by a strenuous hike when changing trains, particularly if burdened by luggage.

As complaints mounted, the Midland contemplated a retreat from the Ingleton branch to engineer its own route through to Carlisle. Faced with the prospect of competition for its Scottish traffic, the L&NWR capitulated and sought a cooperative future. An agreement was eventually reached, but too late: politicians insisted that the new line was built, the result being today’s majestically-engineered route between Settle and Carlisle. This effectively killed off any lingering aspirations of Ingleton-Lowgill achieving main line status.

Ingleton lost its passenger service on 30th January 1954, the last train being played out by the Kirkby Lonsdale Brass Band. Freight continued for another three months. Excursions continued to visit on Sundays and Bank Holidays, whilst specials were laid on at holiday time to collect pupils from nearby boarding schools. The ultimate irony came during the winter of 1963 when the Settle-Carlisle succumbed to severe snow for several weeks and main line traffic was diverted along the branch, finally fulfilling the role for which it was built. But this did not justify the continued expense of maintenance and closure came on 26th July 1966. The track was lifted the following year.

Ingleton Viaduct remains a significant local landmark and harmonises wonderfully with the roofs and chimney pots of adjacent cottages. In contrast, rather more flimsy is the collection of mobile homes occupying a caravan park which the structure passes over.

A Grade II listing was bestowed upon the viaduct in November 1988. It is currently under the custodianship of Highways England’s Historical Railways Estate, structure number INL/88L. In the Noughties it benefited from a major refurbishment but locals turned down BRB (Residuary)’s offer to establish a walkway across its deck as part of the works.