The 'faded glory' of the Queensbury Lines: Great Northern Outpost Vol.3

The ‘faded glory’ of the Queensbury Lines: Great Northern Outpost Vol.3

Back in 2014, an annual report on internet trends found that an average of 1.8 billion photographs were uploaded to social media platforms daily. That’s one for every fourth person on the planet – a breath-taking figure. Whilst each image captures a unique moment in time – and a memory for someone – their long-term value must generally be intangible. That’s not why we take photos, of course, but the production of a social archive has been a happy consequence of us doing so.

We were more thoughtful in exercising our shutter fingers during the era of film and we therefore captured scenes with greater depth, albeit viewed through a rose-tinted filter. The latest offering from Willowherb Publishing – who specialise in colour transport history albums – drips with nostalgia and melancholy, charting the declining years of the Queensbury Lines in West Yorkshire’s Pennine foothills.

The third in a series, ‘Faded Glory’ is dedicated to the post-war railway men and women who battled against the odds to serve customers and communities whilst those further up the management chain conspired to make Queensbury’s three radial routes financially unsustainable. Oh yes they did, such were the prevailing politics.

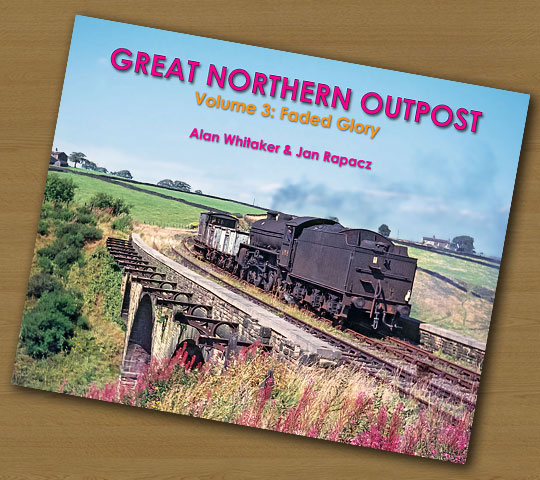

Reproduced with special permission of the authors © Alan Whitaker/Jan Rapacz

Photo: Howard Malham

The village’s station features on the cover as a B1 hauls its light load over the three spans of a viaduct which carried part of the Bradford-Keighley platforms. The coping stones almost look new, presumably installed after the platforms were removed from the parapets to reveal the elegant ironwork which formerly supported them. It’s all gone now.

The book’s main body presents a journey to Keighley from Bradford’s expansive Interchange station – looking desperately austere – and Halifax, where the Great Northern and Lancashire & Yorkshire railways enjoyed a collaborative relationship. This all comes courtesy of photographers who had the vision – and resources – to invest in colour film, although we’re mostly riding within a Sixties landscape which industry had painted grey.

The railway threaded itself unobtrusively through the urban sprawl, hiding in cuttings and tunnels before emerging to snatch land for stations and yards. St Dunstans, Horton Park, City Road Goods, Great Horton, Clayton, Ovenden, Pellon, St Paul’s: we see all these outposts from what is definitely a stopping service.

John Rothera and David Mitchell, in particular, had eyes for infrastructure, recording a collection of structures that have subsequently been torn from the map. A gloomy incursion into Ripley Street Tunnel stands out, as does another looking down towards Manchester Road Tunnel with the tracks in surprisingly fine fettle.

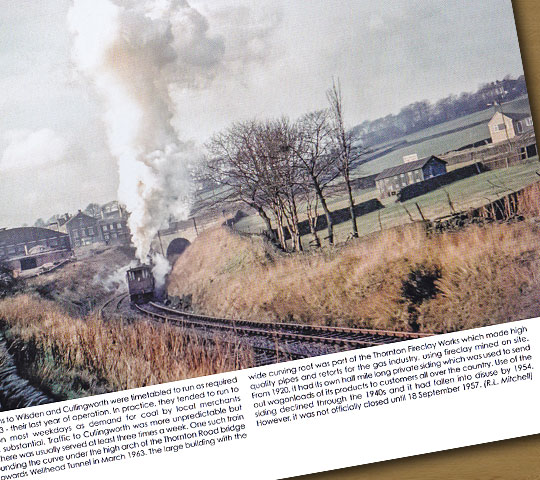

Reproduced with special permission of the authors © Alan Whitaker/Jan Rapacz

Photo: R L Mitchell

Of considerable appeal are views of the routes’ signal boxes, standing sentry over their junctions. Those at Holmfield and Queensbury East are depicted in forlorn states, whilst a view of Horton Junction’s lever frame has a delightful timeless quality. And then there are the modest trackside cabins wherein platelayers would rest; we’re offered two on the approaches to Lees Moor and Clayton tunnels. Whilst drivers and firemen enjoyed the public’s adoration, legions of invisible labourers attended to the tracks in all weathers to ensure their safe passage. Lest we forget.

Possibly most striking is a fabulous panorama of the 25-acre City Road goods yard with its coal drops, six miles of sidings and chimney-strewn backdrop. More evocative is Ralph Wood’s photo of five lads investigating the track-lifting operation at Clayton in 1966, back in the days when kids had real adventures rather than experiencing life through their phones.

A Halifax street scene catches the traffic passing the Great Northern Hotel near North Bridge, long since demolished to make way for a flyover. But for their tonal splendour, there are no better shots than those capturing the vista at the north end of Halifax Station – mills foreground, hills beyond – as a DMU encounters the junction with the line up to Ovenden, and another showing an RCTS Special, paused in the sunshine at Queensbury East Junction whilst its passengers decant to explore the overgrown infrastructure.

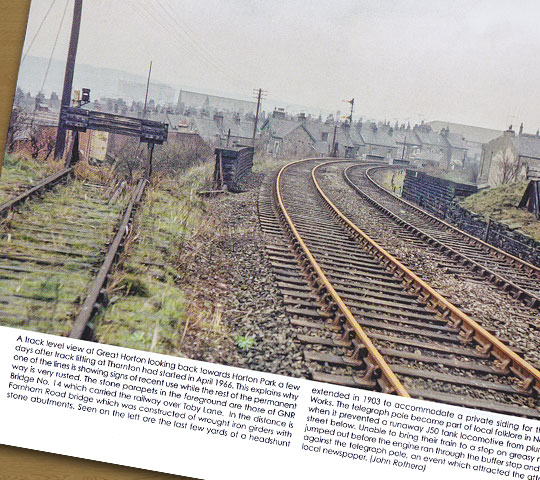

Reproduced with special permission of the authors © Alan Whitaker/Jan Rapacz

Photo: John Rothera

Deep insight into the book’s 106 photographs is offered by the accompanying captions, richly researched by authors Alan Whitaker and Jan Rapacz. We learn that the goods yards at Thornton and Great Horton generated income of £13,086 in 1964; closing them a year later saved the railway just £6,000 annually. And in 1957, a section of closed line near Ingrow was relaid with concrete sleepers to test their durability by deliberately derailing a train onto them!

The historical merit of this album – and the two that preceded it – should not be underestimated. The imagery is rare; despite their exceptional engineering, few photographers considered the Queensbury Lines to be worthy of their spotlights. But no less significant is the pulling together of knowledge about them before it is lost. The attention to detail is exemplary.

Great Northern Outpost Volume 3: Faded Glory has been carefully pieced together by Willowherb Publishing and is available via its website, priced £19.95. Despite the pervading gloom, it serves as a celebration of the engineers, contractors and navvies who overcame adversity to drive these lines through hostile terrain and those who subsequently faced the challenges of operating them.

And we’re left with some brightness. The last photo recalls the reopening of Thornton’s majestic 20-arch viaduct as part of the Great Northern Railway Trail in 2008. Those with vibrant memories of the railway mingled amongst youngsters astride their bikes as the structure prepared for a better future.

As we wrestle our environmental responsibilities with a different mindset after Covid, the benefits of old railways as active travel corridors must increasingly be recognised. This commemoration of the Queensbury Lines in print has to be accompanied by more sections of physical rebirth for walking, cycling and our collective wellbeing.

We look forward to Volume 4.