The Bradford, Thornton & Keighley Railway in colour: Great Northern Outpost Vol.2

The Bradford, Thornton & Keighley Railway in colour: Great Northern Outpost Vol.2

Given its decline under British Rail, today’s railway is an unlikely success story, connecting commuters with their workplaces in comfort, good time and unprecedented numbers. Generally speaking. And make no mistake – despite operational hiccups and fares that make your toes curl – it is now an industry that’s acutely passenger focussed.

But it hasn’t always been that way: travel back to the 1950s and things looked very different. Yes, for many miles, tracks rode the contours of the landscape, much as they still do. Those modest corridors did though contrast starkly with the sprawling goods yards which served local enterprise, interrupting an otherwise linear progression. The modern traveller will never have seen such sights, but now can – in full colour – thanks to a photographic journey along the erstwhile Halifax, Thornton & Keighley Railway, a key constituent of the outstanding ‘Queensbury Lines’. This is captured in a book entitled Great Northern Outpost, the second in a series from Willowherb Publishing.

The HT&KR appeared during a late phase of network development in the 1870s/80s, the hilly topography thereabouts having previously been judged insurmountable. In overcoming that challenge, the Great Northern constructed one of Britain’s great railways, although it never earned the ranking enjoyed by the Settle & Carlisle, built partly by the same contractor. Blessed with tunnels, viaducts and earthworks of equally grand proportions, the Halifax, Thornton & Keighley stood testament to the prowess of John Fowler and his son, Henry, its engineers. But ultimately, the two routes faced different fates.

By the time colour photography came within reach of railway enthusiasts, the line was already on the way out. As a result, the book has no rose tint – most of the images depict a creaking melancholy. There’s grime too – lots of it. Those of a certain age will have memories rekindled of an urban world blackened by industrial belch.

Reproduced with special permission of the authors © Alan Whitaker/Jan Rapacz

Photo: Gavin Morrison

Our departure point is chimney-strewn Halifax, of which broad vistas are offered featuring the station and now-demolished 35-arch viaduct linking it with North Bridge where a sizeable goods warehouse once did thriving business. Dominating every view is a retaining wall – built to address space constraints – extending more than quarter-of-a-mile to the mouth of Old Lane Tunnel.

Tackling the gradient away from town, we arrive at Holmfield – northern end of the Halifax & Ovenden Railway – where an N1 pauses with a two-coacher heading south. It’s 1954 and passenger services are in their last full year. Despite splashes of sunshine, the scene is bleak, much of the station’s infrastructure having succumbed to rationalisation in the 1930s. There is though a signal box, marooned off the platform end, which controlled a set of motorised points that were unique on the Queensbury Lines.

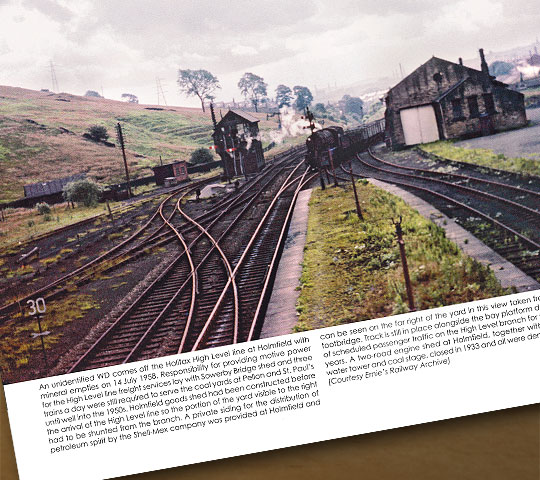

Before joining the HT&KR proper, a diversion is taken along the High Level line to Halifax St Pauls. We learn from an intricately detailed caption – one of many – that the goods facilities at Pellon accommodated both Lancashire & Yorkshire and Great Northern staff in separate offices, but they had to share the same toilet!

The engineering steps up a gear as the line’s two tracks navigate the deep rock cutting at Strines before disappearing into Queensbury Tunnel. About to do the same, in October 1962, is the District Engineer who is seen relaxing in his inspection saloon as an Ivatt tank propels it through Queensbury’s triangular station towards the north portal. A fabulous panorama helps to describe the layout here.

Reproduced with special permission of the authors © Alan Whitaker/Jan Rapacz

Photo: Ernie’s Railway Archive

Beyond Thornton, the route climbs to its summit between two more tunnels before falling again into Denholme Station, the foundations for which had to be sunk 24 feet below track level thanks to “the peculiar nature of the soil”. The sun again does its best to detract from the Fifties’ dilapidation, but rust and flaking paintwork are not so easily hidden.

As the setting becomes more rural, the page is turned on another structural landmark – Hewenden Viaduct, built in stone from the nearby Manuel Quarry and spanning the valley on a sweeping curve. A locomotive retreats over it towards Cullingworth, our next stop. Here, a spring image from 1954 has a more optimistic flavour, with a four-foot free of vegetation and lone passengers loitering on both platforms. In the adjacent goods shed is an unlikely refugee from Sheffield – a double-deck tramcar.

Weeds take over again as Keighley beckons. Getting there involves a passage through Lees Moor Tunnel, constructed without ventilation shafts to the considerable disadvantage of footplate crews. It was a choking hell hole and, hence, a fitting place to host post-closure experiments into the comparative harm of sulphurous steam and diesel fumes.

Towards the bottom of the hill, a succession of bridges and cuttings – now infilled – reintroduce the line to urban living. Three young lads welcome the opportunity to explore an environment that was theoretically off-limits, bedecked in short trousers: a picture very much of its time. The end of the line is close by, goods trains passing under the Worth Valley Railway to reach a generous yard whilst the GN’s passenger services meet the Midland network at Keighley’s joint station. In 1954, we find a Gresley N1 and two coaches ready to start their ascent: destination Bradford.

Reproduced with special permission of the authors © Alan Whitaker/Jan Rapacz

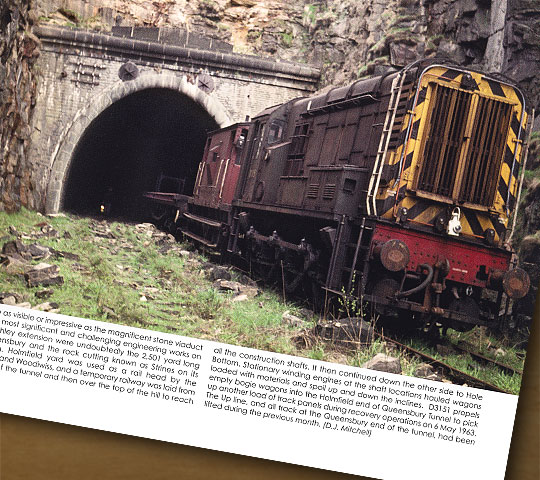

Photo: D J Mitchell

Just like Volume 1 covering the Bradford & Thornton Railway, the reader’s return journey is made alongside the salvage teams who lifted the tracks after closure, mostly over the summer of 1964. Glorious weather was their unwarranted bonus. This activity presented several photographers with the opportunity to blag rides on the demolition train – thankfully grasped with both hands – from which they could acquire unique views of the line and its many structures. Of particular interest is a shot showing the gantry machine, used to remove the Down line from the confined space of Queensbury’s 2,501-yard tunnel.

The book’s contributors – notably David Mitchell and John Rothera – performed a fine public service by pointing their cameras at the overlooked Queensbury Lines. But that foresight would have little value without authors Alan Whitaker and Jan Rapacz whose deep research over 40-plus years unearthed the evocative imagery and stories behind it. They’ve done a cracking job. The atmosphere might be gloomy, but it’s a vibrant trip with the richest possible commentary.

Great Northern Outpost Volume 2: The Halifax, Thornton & Keighley Railway is brought to us by Willowherb Publishing and is available via its website (click here to visit the Buy Now page), priced £19.95.