The Buckinghamshire Herald reports on the... Watford Tunnel collapse

The Buckinghamshire Herald reports on the… Watford Tunnel collapse

Awful occurrence at the London and Birmingham Railway

Thursday morning week the town of Watford, and the country for many miles round, was thrown into a state of the greatest excitement and alarm, in consequence of a report gaining rapid circulation, and which, unfortunately proved too true, that one of the shafts of the tunnel of the intended railroad to Birmingham, which runs through the Earl of Essex’s estate, at Russell Farm Wood, about two miles beyond Watford, had fallen in, and been attended with an immense sacrifice of human life. In the course of a few hours thousands were drawn to the spot, and the scene that occurred is indescribable. The wives and families of those who were employed about the works might be seen running to and fro in a state of frantic despair, ignorant which of them had been bereaved of their husbands.

The following are the fullest particulars that our reporter has been able to obtain. The shaft in which this lamentable affair took place is situated amidst Russell Wood, a very picturesque spot, and the approach from Watford would lead few to expect that the line of the Birmingham railroad was 80 feet below the spot. The shaft in question, one of the four in this length of tunnel (1,700 yards), is termed a gin-shaft, and has been sunk about 90 feet below an elevated platform erected for the purpose of removing the earth. The shaft has been very lately sunk, and two nine-feet lengths of tunnel had been bricked, the third being, it is stated, just mined and ready for the bricklayers. The shaft was about to be bricked on Friday morning, between 5 and 6 o’clock, by a party consisting of five bricklayers and six labourers, who composed what is termed the night gang; and had the appalling event taken place a few hours afterwards, the morning gang would have been at work, and the loss of human life must have been awful in the extreme. As it is, it is impossible to state correctly the number of victims that have fallen by the dreadful catastrophe, as not one out of the number that was at work is left to tell the dismal particulars.

In loosening a portion of the wood work previous to bricking the shaft, it is supposed the earth gave way and buried the unfortunate men, carrying the whole of the wood work with it. When the earth fell a horse and gig were partly buried beneath, and it was with great difficulty the horse was extricated, and it was discovered that the poor animal had sustained much injury. Fortunately however the man attending to the gin heard some of the earth in the shaft fall, and, feeling the ground under his feet giving way, he made a precipitate retreat, and providentially escaped, while a dog that was lying by his side was buried with the earth.

The falling of the immense quantity of earth into the shaft has caused an abyss of about 35 feet deep, and about 40 feet in breadth. It presented a fearful appearance, and it was with the greatest difficulty that other accidents were averted, from the imprudence of the surrounding inhabitants in gratifying their curiosity. The names of all the unfortunate sufferers we have not been able to ascertain, but it is known that among them are Mr Barker, the sub-contractor; Mr Jordan, inspector of the brickwork; and Benson, a miner, all of whom have left wives with large families to bemoan their loss.

The men must be buried upwards of 80 feet below the surface of the earth, and although 60 men are actively engaged in digging out the bodies, it is probable that six or seven days will elapse before they are extricated.

About half-past 8 o’clock on Friday night, it was reported to the timekeeper of the shaft, that in driving the heading way of the tunnel from the next shaft, the groans of some of the sufferers were heard. He immediately went to the spot, and found that the men employed in digging had actually introduced themselves into that part of the tunnel which was bricked over, and got hold of the gin-rope, but were unable to find any of their unfortunate fellow workmen.

In the course of Friday the Earl of Essex and Lord Clarendon expressed the utmost concern for the sufferers. Lord Clarendon benevolently stated his intention to provide for their wives and families, and a liberal subscription was entered into by the inhabitants of Watford.

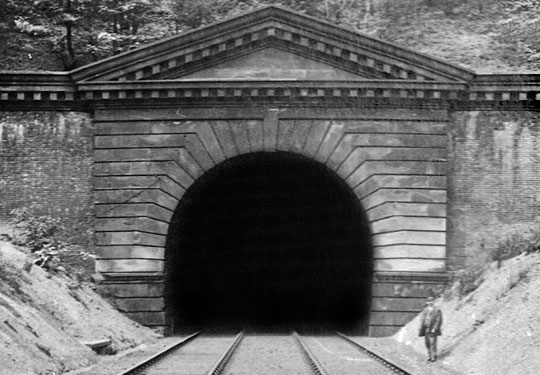

(1).jpg)

© National Railway Museum and SSPL (Reference 1997-7409_LMS_396)

(from NRM website, used under Creative Commons licence)

(From the Standard of Monday)

The following report of this lamentable occurrence has been forwarded to us by the Secretary of the railway company – London and Birmingham Railway, Office, 83, Cornhill, July 18.

Mr Creed presents his compliments to the Editor of the Standard, and encloses the copy of a report of the Directors of the London Committee, who attended at Watford yesterday to investigate the circumstances connected with the late lamentable accident at the tunnel – London and Birmingham Railway, Watford, July 17.

(Report)

Information having been received from Mr Buck, the superintending engineer of the works of the London and Birmingham Railway at Watford, that an accident, attended with loss of life, had occurred at the new shaft near the observatory on the tunnel, Mr Solly, the Chairman of the London Committee of Directors, accompanied by Mr Tooke, Mr Rowles, and Mr Calvert, Directors, Mr Creed, the Secretary, and Mr Stephenson, the engineer of the company, immediately left town for the purpose of investigating the circumstances connected with the accident on the spot.

It appears from the information which the Directors have collected –

- That the summit of the shaft at the base of the tunnel is a depth of about 100 feet.

- That two nine-feet lengths of the tunnel had been bricked to the south of the shaft, and one nine-feet length to the north, and that another nine-feet length had been excavated from the crown of the tunnel to the springing of the arch, the brickwork of which was not commenced.

- That the shaft had been sunk in chalk throughout its depth.

- That the bricklayers had nearly completed the arch of the shaft length of the tunnel ready for the reception of the cast iron curb at the time the accident occurred.

- That Mr Cropper, sub-contractor for the brickworks was in the tunnel at 11 o’clock on Wednesday night, when everything appeared secure.

- That at half-past five in the morning of Thursday, Thomas Jordan, the overlooker, and nine men (as enumerated below), being at work, the man who attended the gin heard a cry of “ware”, that the ground fell in at the same instant, and, so suddenly, that his dog was buried in the abyss, the gin and gear carried down, and that he only escaped by being entangled in a part of the machinery above ground.

- That the candles of the men at work on the length of tunnel in the next adjoining shaft on the north were blown out by the rush of air through the heading, or drift way, when the ground fell.

- That on an examination of the tunnel, by the heading or drift way, it is found on the north of the shaft to be filled up, and that on the south side the brickwork has been very little injured. That portions of the remains of four men who were crushed, and are completely dead, can be observed on this side, but that the attempt to extricate the bodies through the heading, would be attended with the certain loss of more lives.

- That the ground must have fallen in upon the men who were standing upon planks, close to the crown of the arch, so suddenly, that not one of them had time to save himself by the heading, although within 18 feet of it, and that the mass is so enormous, as to leave no hope of any individual having escaped with life.

- That the contractor, with the concurrence of Mr Stephenson, is sinking a shaft of the breadth of the tunnel, as the only practicable mode in the loose state of the soil of working safely to the bottom.

- That it will be the end of next week before the bodies can ne extricated.

- That the individuals engaged on the works on the shaft having all perished, the proximate cause of the calamity can only be conjectured.

- That it appears probable there existed a fault in the chalk immediately adjoining the shaft, and that the crust of chalk yielded to the pressure of the superincumbent gravel at the moment of some support being withdrawn.

- That there does not appear to have been any want of attention to their duties on the part of those engaged on the works.

- That, however deplorable the loss of life on the present occasion, it is some consolation to know that, as far as can be ascertained, only one man has left a widow, and but one other, Jordan, the overlooker, who was a widower, two orphans.

With reference to the works, it may be added that the event will not have the effect of delaying the period assigned for the completion of the tunnel.

By order, R Creed, Secretary

© Forgotten Relics collection

Names of the men who were employed on the shaft: Thomas Jordan, overlooker, widower. Thomas Evans, bricklayer, unmarried. Sylvanus Rubings, ditto, ditto. John Clarke, ditto, ditto. William Byrd, ditto, ditto. George Platt, ditto, ditto. Thomas Winmill, labourer, married. James Darvill, ditto, unmarried. Another labourer, name unknown, ditto. James Barker, foreman, miner, ditto.

Saturday 25th July 1835: Buckinghamshire Herald

The Late Accident at Watford

After more than a month of incessant exertions on the part of Messrs Harding and Copeland, the contractors for the Watford line of the London and Birmingham Railway, and a vast number of labourers who were relieved every twelve hours, the bodies of some of the unfortunate men, who were buried under more than eighty feet of earth, by the sudden falling in of the shaft in Russell Wood, Levesdon Green, Watford, in this county, have been dug out. Early on Saturday morning the miners were enabled by crawling between the interstices made by the fallen timbers, the see the legs of some of the sufferers, and to know that before many more feet of the gravel and chalk had been removed (the distance from the surface being about eighty-four feet) they would come to the bodies. The greatest interest, as may be anticipated, was consequently excited, and many persons from Watford, and the whole surrounding neighbourhood, including several scientific and practical men of the county, were present during the later period of the day.

At three o’clock in the afternoon an extended hand presented itself to the view of the bystanders, on the side of the opening opposite to that which the first eruption of the gravel is supposed to have taken place. The body on being cleared was found in a sitting posture, with the head thrown back; it is presumed the poor fellow was looking upwards at the moment he met his death, have heard the cry of “ware” from the men at the top of the arch; his face was crushed and the legs broken.

The first body taken out was lying on one of the bars, a piece of timber about six inches in diameter. He was in a horizontal position, with the whole weight of the gravel upon him; his hands were extended and his knees bent up. The third body was found in the immediate vicinity of the others; it was discovered his bowels had burst by the sudden pressure of the timber upon him. The fourth sufferer was lying amongst the centres, much crushed by the gravel. The fifth body was found with the head fixed fast in one of the centres in a downwards position. The sixth was lying with his back upwards and his left hand bent under him.

The strata in which the whole of them were found was gravel and sand, which it is probable came from the vein of gravel and sand on the side which led to the accident. About twelve o’clock on Saturday night a seventh body was also found. The whole were as quickly as possible placed in coffins, which were ready on the ground, and conveyed in a hearse to Watford.

The names of the men dug out are thought to be John Betts, a bricklayer; Wm. Byard, Silvanus Rudings, Thomas Windmill, Joseph Darvill, Bartlett Scones and James Corrie. Several of their relatives were in the shaft when the men were dug out (in which they assisted), but they were scarcely able to recognise a feature, as decomposition had taken place to such an extent as to render positive and perfect recognition almost impossible, the dress of the deceased men forming the only clue to identity.

(2).jpg)

© National Railway Museum and SSPL (Reference 1997-7409_LMS_8627)

(from NRM website, used under Creative Commons licence)

F J Osbaldeston Esq, the county coroner, on being informed that some of the bodies had been taken to the Watford poorhouse, from fear that any delay in their interment might endanger the health of the inmates, issued his warrant for holding the inquest at one o’clock on Sunday, intending then to swear the jury, receive evidence of identity, and to allow the bodies to be buried, and then adjourn the inquest. With proper promptitude he repaired to the spot early on Sunday morning, to collect such information by a personal inspection as would enable him satisfactorily to conduct the inquiry. On his arrival there he found several from Watford, from whom he learned the fact of the bodies been placed in the engine house, a place so far removed from the workhouse ass to prevent infection, and that there was great probability of the other bodies being shortly got out. He therefore postponed the inquest until such time as the whole were extricated.

The opening made for the purpose of getting at the bodies is timbered all round, it is about forty feet square, and goes to a depth of eighty-six feet. The number of men constantly employed in the excavation is stated to be forty, and the timber used in the shoring is valued at £1,000. The subscription of behalf of the widows and relatives exceeds £300 and, no doubt, other sums will be raised when their case comes to be properly investigated by the committee, of which the Hon and Rev W Capel, rector of Watford, is at the head.

Vast numbers of respectable people on Sunday visited the place. At four o’clock on Sunday afternoon the church wardens of Watford permitted the relatives to see the bodies. The scene was one of those so truly said to be better imagined than described. Darvill was identified by his widow, Betts by one of his family, who spoke to his dress; Thomas Windmill was identified by means of his shoes, Rudings by his widow who fainted away on her seeing her deceased husband; a sister of Bartlett Scones identified him, and the other two bodies were not recognised.

Inquest

On Monday, at noon, a jury met at the Essex Arms, Watford, before Mr F Osbaldeston, coroner, to inquire into the cause of the death of Thomas Jordan, Joseph Barker, Thomas Evans, Silvanus Rudings, John Betts, William Byard, Thomas Windmill, James Darvell, and Bartlett Jeans, nine men killed by the falling in of a part of the tunnel forming in Russell Wood, near Watford, on the line of the London and Birmingham Railway.

The coroner having briefly explained the law relating to deodands, the jury proceeded to take a view of the bodies, which were lying in the engine house. They presented a most sad spectacle.

William Dixon, a lad of 14, deposed that he was descending the gin (a horse pulley) at the shaft in Russell Wood on Thursday, the 16th of last month. The men were down the shaft at work, of whom witness only knew the names of Jordan Rudings, Byard and Windmill. Jordan went down between 5 and 6 o’clock that morning. He is the overlooker, and Barker (another of the men down) was foreman of the gang. Rudings and Barker had been up that morning and had gone down again two or three buckets before Jordan. In about ten minutes after Jordan went down, witness heard the cry of “Ware” and immediately the whole shaft fell in. Witness was himself very near being killed. The shaft closed at the top. Neither Jordan or Barker had a saw when they went down.

William Tell was banksman on the morning of the accident. Ten men were down the pit at the time. After speaking to the time the men went down, he proceeded to state that it was his duty to stand at the mouth of the pit to let the materials down. About three o’clock the men called out to him not to send any more bricks until they had finished the part they were at work upon. When the pit fell in witness had got hold of one of the posts, and saw a man run across the pit. It was about twenty minutes to six o’clock. The whole fell in from the bottom to the top in less than two minutes. Witness had not time to look round him, and he could not say which way the man ran. He ran away in consequence of a noise he heard in the bottom of the pit, like the shooting of gravel out of a cart. The whole of the machinery of the gin was broken, and the horse was got out with great difficulty alive. The pit gave way at the bottom. The gravel ran in from all sides. Witness before the accident had assisted in digging out the tunnel, looking towards Birmingham, the gravel is on the right-hand side, and the chalk on the other.

Examined by Mr Buck – witness helped to get the shaft length out. One side is gravel, the other side chalk. Witness knew there was gravel, because they had to put up boards to prevent it running. The first length of the tunnel was arched over before the men began the second length. A bar is put along the chalk which rests on the brickwork at one end, and on a prop at the other.

.jpg)

© Chris/British Listed Buildings (used under Creative Commons licence)

John Cropper deposed that he was the sub-contractor, under Messrs Harding and Copeland, for the whole of the tunnel and shafts on the Watford line of the London and Birmingham Railway. Witness had to do all the brickwork. On the 16th of July the extra shaft fell in. Witness was at home at the time of the accident, but had been down the shaft the night before, at about eleven o’clock. At that time the bricklayers were bricking up the tunnel close to the shaft. About six yards on either side had been done. There was about ten feet space between the two brickworks. The space of the tunnel is 24 feet, and they had bricked when witness was down about three feet above spring of the arch. It had been previously secured by bars. On the right-hand side of the Birmingham side the soil is chalk; the other gravel. In the shaft length there was about eighteen inches of chalk in front of the gravel. In the shaft length the chalk ran for about twenty feet from the crown of the arch, proceeding upwards. Everything was safe when witness was down, and he had no reason to apprehend the least danger. Witness had known Barker some years and had worked with him at the Leicester tunnel; he was an experienced miner, as was also Jordan. Witness had worked in the tunnel on the previous night and had helped to get the centres up. Witness had never been told that the shaft was unsafe, and he never believed it to be so. There is four feet distance between each centre; one of which is placed in the middle of the shaft, and two others at four feet distant on either side. When the brickwork is completed at one centre, we strike the centre, and carry it onto the next. The bars are struck at the brickwork comes on, if they are in the way of the work. The bars are pieces of oak, about 13 feet long by 7 inches diameter, used to support the chalk until the brickwork is put in. Sometimes they are struck, and sometimes not. Since the accident, witness had been down the tunnel; the soil that fell in consists of chalk and gravel, of which there was none in when witness left the night before. In striking a bar the chalk might be broke, and if the gravel was so near the bar it would cause it to rub in. The bars rested on the chalk; there was no gravel visible in that length. He did not know how thick the chalk was. As a practical man he should have hesitated to strike either of the bars, even if he had not known of gravel being there. Mr Buck, the resident engineer, had been down No.2 shaft, and on seeing the gravel there told us to be cautious. We put good strong timbers in. Witness believes Mr Buck was there many times when he did not see him. No gravel was observable in the drift way. We have dug gravel in all the pits. The Leicester tunnel had sand in it, and we did not take any greater precaution there than here. Witness considered that there was more apparent danger in shaft No.2 than in the one that fell in. He knew of no means likely to make the tunnel safer than it then was.

W Barker, brother of one of the deceased men, deposed that his brother had followed mining ever since he had been able to work, and that he possessed considerable experience, having been employed at Leicester and other tunnels. Witness is also a miner. He had worked in the extra shaft the night before the accident, and he considered the soil there not to be so dangerous as that at Leicester, which was sand. The same precautions against accidents were taken at both places. Witness was present when the body of his brother was found; he was much pressed by the bar, and lying on the gravel side of the pit.

W Phillips described the situation in which the bodies were found. He then proceeded to state that on making the excavation for the purpose of getting the bodies out, they found a chalky soil on one side and gravel on the other. The bodies were lying on sand, chalk, and timber, all mixed together.

Mr Stephenson, engineer to the railway company, stated that he had directed in all cases in which any danger was feared from the presence of sand, that six feet and four feet lengths should be worked. Mr Buck, the resident engineer, had unlimited power as to any expenses necessary to render the work safe. He further stated that he had been employed as the engineer of the Leicester tunnel, and could confirm what had been sworn to with respect to greater danger there than at Watford. The shaft length of the Watford was obliged to be worked in a nine feet length.

Mr Buck, the resident engineer, made a similar statement.

James Simpson deposed that he was superintendent of the works on the part of the company. He had been down the tunnel 10 days before, and did not see any gravel; and on sinking the shaft now to get at the bodies, he found some chalk remaining in the form of the tunnel. The value of bricks, centres etc in the shaft was worth about £200.

The coroner then called the attention of the jury to the questions for their decision, as to whether they considered any blame to attach to any party, then for them to say to whom, and what was the amount of the deodand. The timber, bricks etc had been sworn to be of the value of £200, and they might find a verdict for that sum if they thought fit.

The jury, after a short consultation, found a verdict to the effect of the cause of death being entirely accidental, and levying a deodand of £5 on the bricks, timber etc. They further stated, that in their opinion every possible care and attention that skill and science could dictate had been used on the part of the company, their agents, and superintendents, in the construction of the shafts and works which had been brought under their notice.

The bodies of the unfortunate men were buried in Watford Churchyard the same evening.

Saturday 22nd August 1835: Buckinghamshire Herald