Major A Ford reports on the... Hose Tunnel explosion

Major A Ford reports on the… Hose Tunnel explosion

I have the honour to report that in obedience to your Order of the 7th November 1876, under the 66th section of the Explosives Act, 1875 (38 Vict. c.17), I have made an inquiry into the cause of an accident by an explosion of gunpowder which occurred at Hose Tunnel, near Scalford, in the county of Leicester, on the 14th October 1876, by which two persons lost their lives and six others were injured – one very severely. I also attended the adjourned inquests on the deceased at Scalford and Melton Mowbray which were held by Mr Oldham, the coroner for Leicestershire, on the 10th November; owing, however, to the injuries received by the principal witness in the case, he was unable to give evidence on that occasion, and the inquests were further adjourned to the 13th December, when I again attended.

In accordance with the provisions of the aforesaid section, I beg to render the following report –

Site of explosion

Hose Tunnel is now in course of construction by Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss, contractors, on a joint line of the Great Northern and London and North Western Railway companies, intended to run from Melton Mowbray to Bottesford. It is being excavated through a hill which is near the village of Scalford (about four miles from Melton Mowbray), and when complete will be nearly half a mile in length. In order to expedite the work, shafts have in accordance with the usual custom been sunk at intervals; and at the bottom of each shaft men excavate in both directions. In this way the construction can be carried on much more rapidly than if the cutting away were restricted to the two ends of the tunnel, each shaft giving two extra “faces”, as they are termed, for the men to work upon.

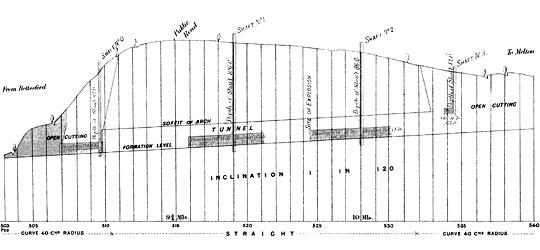

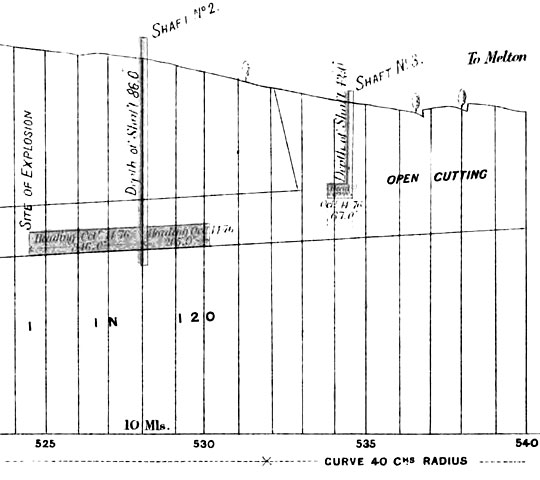

The accompanying sketch (above) shows the actual state of the tunnel on the 14th October, when the explosion took place. There were then two shafts (Nos. 1 and 2) sunk to the tunnel proper, in which men were at work, and two other shafts (Nos. 0 and 3) in what will ultimately be an open cutting.

A “face” is about 11 feet high and 12 feet wide, and is divided into two “lifts”, the upper and lower; the upper lift being three or four yards in advance. A “shift” or gang of some 15 men are employed in each shaft under a foreman; but in the actual excavation only about three men can work on each lift, the remainder having to remove the earth to the bottom of the shaft, and to timber up the sides and roof of the tunnel as it is formed. On the 14th October there were altogether 17 men in the shaft No. 2, eight of whom were at the end of the tunnel where the explosion occurred (marked “site of explosion” on the plan).

Method of construction of the tunnel

In the Hose tunnel principally hard clay is encountered, and the method of excavation is to remove a certain portion on each side of the lift by manual labour, when two or three large holes (about three inches in diameter and about three feet deep) are bored into the centre part thus left unsupported at each side, and this portion is detached by blasting with gunpowder. The work is carried on by night as well as by day, the shifts relieving one another at 6am and 6pm, but on Saturday the day shift works from 6am to 2pm, and the night shift from 2pm to 10pm. Work is resumed by the day shift at 6am on Monday. Blasting usually takes place twice during each shift. The progress made at each face averages about one yard per diem, and the tunnel will not be completed for some months from the present time.

It will be observed that a tunnel while thus in course of construction by means of shafts consists of a number of underground places which in no essential particular differ from mines, as far as labour is concerned; yet, while stringent rules as to the use of gunpowder are laid down in the Mines Regulations Acts (35 & 36 Vict. cc. 76 and 77) for the latter, tunnels appear to be under no statutory regulations in this respect, as the Acts referred to do not seem to apply to them. Had there been no more than four pounds of gunpowder in the can taken into the tunnel at the time when the accident to which this report relates occurred, as would have been the case had it been a mine within the meaning of those Acts, I have little doubt that both the men whose lives were sacrificed would have escaped, and probably nearly all of the other six men would have been uninjured.

Storage and use of gunpowder by the contractors

The gunpowder used for blasting in the tunnel had been kept by the contractors in a store roughly constructed of large blocks of earth with a slated roof. Boards covered with sawdust formed the floor. The building was unlined, and there were apertures under the roof and by the side of the door. The contractors had not applied for a license for the store to the local authority, as required by the Explosives Act, and had they obtained such license, the store, as will have been seen by the description I have given, would have failed in very many respects to satisfy the conditions laid down in the Order in Council relating to stores; indeed, it was a most unsatisfactory place for the keeping of gunpowder. Moreover iron spades were also kept therein.

Owing to the necessity for a further adjournment of the inquests to the 13th instant, I was aware that considerable delay must occur in the rendering of my Report, and I therefore made a special Report on the illegality of this store on the 13th November, and the attention of the Local Authority was thereupon called to the matter. I have since been informed by Mr Benton that a new store has been now built, and that application has been made to the Local Authority for a license for the same.

It was the practice to take the gunpowder into the tunnel, when the holes were ready to be charged, in a can holding from 12lbs to 14lbs. The can had a long projecting neck with a sliding cover which would hold about 8oz or 10oz of gunpowder, and was called a “tot” by the workmen. It served as a measure of the amount of gunpowder to be used, three or four “tots” being sufficient for a charge; and the gunpowder, after having been poured from the can into the “tots” was projected with force therefrom by striking the “tots” against the side of the hole. The object of this was to ensure the gunpowder reaching the bottom of the hole and to prevent it from adhering to the sides.

There were no rules issued by the contractors for the guidance of the men in charging the holes, or indeed for any other purpose; the whole regulation of the work was left to the foreman of each shift. The general result, so far as the use of gunpowder was concerned, was that the foreman appears to have contented himself with telling the men to be careful, and to put their naked candles at a safe distance when they were charging their holes. As, on the one hand, placing the candles at a distance from the hole into which the gunpowder was to be “projected”’ involved an absence of light, which was most necessary for the purpose, and as, on the other hand, the question as to what would be a safe distance was left to the individual opinion of the workmen, it is not to be wondered at that the unprotected candle was sometimes left within two or three feet of the hole while it was being charged. Under these conditions nothing could be more natural, or I might say inevitable, than that in projecting the gunpowder down the hole a workman should occasionally make a mistake in the direction in which it was to be thrown, and that striking on some irregularity in the face near to the hole the contents of the “tots” should be scattered and be ignited by coming into contact with the nearest naked candle. In point of fact, there is no doubt that this was what happened on the occasion to which this report relates, with the result as above stated, that two lives were lost and six men were more or less injured.

Circumstances of the explosion

About half-past nine o’clock on the evening of Saturday the 14th October, eight men were in the north or Bottesford heading of No.2 shaft near the place marked “Site of explosion” on the plan. Three, John Sismey, Samuel Longman and John Foster were at work at the upper lift; and three, Samuel Lee, Charles Finch, and Robert Cann were about three or four yards from the face of the lower lift, and therefore about six to eight yards behind the first three. These were engaged in timbering up or supporting the sides and roof with planks. Some three yards further back William Taylor was running out earth, and about 15 yards behind was Thomas Wheeler the foreman of the shift.

On the upper lift, where the three first-named were employed and the explosion occurred, the sides had been cut away, and Sismey having made a hole obliquely in the earth on the bottom had already charged it with gunpowder and was stemming it with clay, sitting down for the purpose behind Longman, who was in the act of charging another hole which was in the face of the tunnel. Near to Sismey there were two candles a short distance apart on the ground, and Longman was lighted by a candle placed in the face about two feet from his hole and a little above it. Foster was working at the side. The can containing the gunpowder was on the ground close by, and Longman having filled the “tot” for the third or fourth time therefrom, attempted to project the contents into the hole, when, as he stated in his evidence, he accidentally struck it against some projecting earth on the face and scattered the gunpowder, which, coming in contact with either his own or one of Sismey’s candles, was ignited. The gunpowder still remaining in the can was exploded, as also that in Longman’s hole; but Sismey’s hole was not fired. The three men on the upper lift were all very seriously injured. Foster died on the 28th October and Sismey on the 3rd November. Longman, who received the discharge of the gunpowder from the hole be was engaged in charging in his face, was still in a dangerous condition on the 10th November, and unable to give evidence at the adjourned inquest. On the 13th December, however, he had nearly recovered, and was able to give an account of the accident. All the other men also in that portion of the tunnel were more or less burnt, including the foreman, who was upwards of 20 yards from the can when the gunpowder exploded, and the three who were nearest on the lower lift were so badly injured that they had not returned to work on the 10th November, or nearly a month after the occurrence.

The principal witness in the case was Longman, the author of the mischief. He gave his evidence in a straightforward way without any attempt at concealment, and I have no doubt that the occurrence happened in the way he stated, viz. by his striking some projecting earth accidentally with the “tot” which contained gunpowder. Evidence was, however, given at the inquest that Sismey, who was carried to the infirmary of the Melton Union with him, had charged Longman with being habitually negligent in not removing his candle to a safe distance when charging his holes; but, on the other hand, Foster said that the occurrence was purely accidental, and that no one was to blame for it. There can be little doubt that the candle was not at a “safe distance” for such a dangerous operation, as the event shows, but it is very possible that Longman may have supposed that it was at a sufficient distance to ensure safety. He had always placed his candle, he stated, about the same distance from the hole, and he apparently argued that because no accident had to his knowledge occurred in this way, no such accident was probable or possible.

Cause of explosion

The primary cause therefore of the explosion was Longman’s accidentally scattering the gunpowder while he was charging his hole; but had the can been kept covered, or had there been only a small quantity of gunpowder – just sufficient for the purpose required – sent down into the tunnel, in all probability no one but Longman himself would have been injured, with the exception perhaps of Sismey and Foster (now both dead), who might have been slightly burnt by the discharge from Longman’s hole near to them. There must have been about 8lbs of gunpowder still remaining in the can at the time of the explosion.

Question as to blame to be attributed

The question then arises, to whom must blame be attributed for the loss of these two lives, and the injuries inflicted on the six other persons? In answer to this question I would observe –

Although the contractors, Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss, may leave the method of carrying on the work in each shaft to the foreman of the gang employed in it, the responsibility of providing for the safety of their men, and of taking all due precautions against accidents, rests with them. In the present case, what were the precautions adopted? We find, first, absolutely no rules or regulations whatever by the contractors themselves as to the use of gunpowder in blasting, all the details being left to the foreman; secondly, a can containing about 12lbs of gunpowder was sent down the shaft, when a much smaller quantity (such as 4lbs, the amount which would be allowed in a can in a mine) would have been quite sufficient for the purpose; thirdly, the foreman allowed the cover of the can to be used to “project” the powder with force down the hole, the men being told to put their naked candles at a “safe distance”, what is a safe distance being left to the men to decide. It is not very much to be wondered at under these circumstances that a man was found so projecting his gunpowder with his naked candle on the face about 2 feet from the hole, while another man was sitting on the ground behind him, stemming his own hole with two naked candles near him, and with the uncovered can containing gunpowder close by. I consider that Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss are very much to blame for this state of things, and that a grave responsibility attaches to them for permitting their work to be carried on without any proper regulations for the use of gunpowder in blasting.As regards Longman, it cannot be said that he exercised due prudence and caution when charging his hole by “projecting” the gunpowder into it under the circumstances stated. But it must be admitted that the method he adopted was the recognised plan in the tunnel; he had become accustomed to charge his holes with the candle at no greater distance, and never thought it possible that he should scatter the gunpowder by striking the face of the tunnel. A stranger to this method of working would no doubt have thought differently, and have rightly considered it a most dangerous practice; but Longman had become used to it, and considered it safe, and immunity from accidents hitherto had so far favoured this view. But this only furnishes another reason why proper and sufficient rules should be laid down in all cases where explosives are to be handled or used. On the whole, therefore, although there is no doubt that great blame attaches to Longman for his want of caution, it is, in my opinion, scarcely such as would render him criminally responsible. The primary responsibility in the matter appears to me to attach to Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss.# The inquests

As there were two inquests, one at Scalford on John Foster, before a jury of that village, which is near to the tunnel, and the other at Melton Mowbray on John Sismey, before a jury assembled in the town, the facts of the case had to be elicited on each occasion. At Scalford the verdict was as follows –

“The jury find that the deceased John Foster died from the effects of burns caused by an explosion of blasting powder in Hose Tunnel, now being made on the Great Northern and London and North Western Joint line, and that such explosion was caused by the carelessness of Samuel Longman, but that such carelessness does not amount to criminality. And the jury further add that in their opinion “based upon the evidence brought before them”, the mode of performing blasting operations in the said tunnel is defective in arrangement, and during its progress lacks proper supervision. They recommend that cartridges be used in lieu of loose blasting powder. But in the event of such powder continuing to be used in a loose state, that not more than 4lbs be sent into the tunnel at one time to one set or gang of men, and that properly protected lamps be used instead of naked candles. The jury request Her Majesty’s Inspector who has attended this inquest to forward this expression of their opinion to the Secretary of State for the Home Department, and the coroner to forward it to the contractors for making the tunnel.”

At Melton Mowbray the jury found a verdict of “Accidental death”, and special blame was attributed to no one.

As regards the first of these verdicts, I would remark that during the course of my inquiry and at my attendances at the inquests, I put questions to the different witnesses in the case. I asked among other questions, why the gunpowder was not used in the form of cartridges in the tunnel, why such large quantities were sent down at one time (pointing out the regulation in the Mines Act prohibiting more than 4lbs being taken into a mine in any case or canister), and why it was necessary to use naked candles when the holes were being charged. No evidence having been adduced to show that these precautions might not have been adopted, the jury, without any suggestion whatever on my part, made the recommendation contained in their verdict; and I now have the honour to forward to you this expression of their opinion as requested by them. I would beg to add that it has appeared to me during the inquiry I have held that there is no valid reason why tunnels in course of construction should not be regulated in the same way as mines, viz. by the Mines Regulation Acts above referred to, at any rate as far as the use of blasting powder is concerned, if not in other respects; and there would be many advantages, in my opinion, in their being placed under the supervision of the mines inspectors.

Where a tunnel takes several months to construct, and the details of the working in the shafts are left to the foreman of each gang, and no rules or regulations are issued by the contractors, there cannot be much doubt that considerable supervision is necessary.

As regards the second verdict, viz. that at Melton Mowbray, I would explain that the jury considered that Longman’s striking the face and upsetting the gunpowder was purely accidental, and hence they returned their verdict as “Accidental death”, attributing blame to no one. They appeared not to take into consideration the method of work in the tunnel, or indeed the question as to whether due caution was exercised by Longman in charging his hole. Although, as before stated, the blame to be attached to Longman does not in my opinion amount to criminality, I consider that he was to a certain extent culpable, and therefore I cannot agree with this verdict of the Melton jury. Further, I also consider, as previously explained, that a very heavy responsibility rests upon the contractors for neglecting to make due provisions for the safe conduct of their work.

I have to add that I received every assistance from Mr Oldham the coroner at the inquests, and Mr Benton, of the firm of Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss, the contractors, afforded me every facility in making my inquiry. I also had an opportunity of inspecting the work as actually carried on in the tunnel.

A Ford, Major RA, HM’s Inspector of Explosives