Major V D Majendie reports on the... Cymmer Tunnel explosion

Major V D Majendie reports on the… Cymmer Tunnel explosion

I have the honour to report that in obedience to your Order of 6th instant, made under the 66th Section of the Explosives Act, 1875, I have held an inquiry into the circumstances attending an explosion of dynamite which occurred at Cymmer, near Maesteg, Glamorganshire, on the 21st April 1876, by which 13 persons lost their lives and two others were injured. I also attended the adjourned inquest on the deceased which was held at Cymmer by Mr Cuthbertson, coroner.

.jpg)

Photo: Richard Knight

In accordance with the provisions of the above-mentioned section of the Act, I beg to furnish the following report –

Circumstances under which the explosion occurred

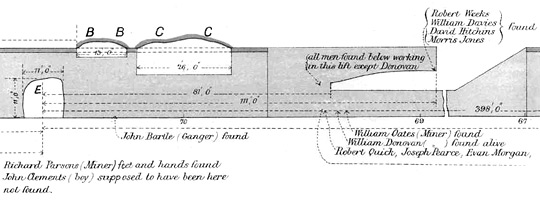

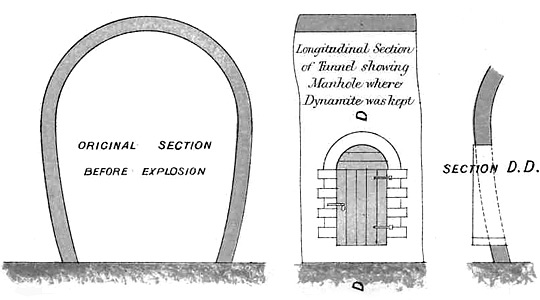

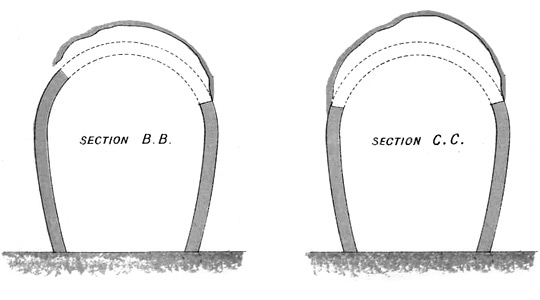

The explosion took place in an unfinished tunnel, forming part of the Llynvi and Ogmore Railway Extension. This tunnel which, when completed, will be nearly a mile in length, is being driven through a high hill lying between Maesteg and Cymmer by the Diamond Rock Boring Company (Limited), of 2 Westminster Chambers, Victoria Street, SW. The work at the time of the accident was being carried on from both ends, and at the north or Cymmer end a distance of 365 yards had been penetrated. At 8.30pm on the 21st April an explosion occurred at a manhole, situated in, and on the left side of, the tunnel, 176 yards from the mouth, by which 13 persons were instantaneously killed and two others sustained serious injuries. Some damage also was done to the tunnel, portions of the roof of the heading being injured, in one case at a distance of 118 yards from the scene of the explosion, and the wooden centres at the opening of the tunnel distant 176 yards being blown away.

The names of the persons who were killed were –

| John Bartle | 30 years | body or remains found 18 feet from scene of explosion |

| Robert Quick | 25 years | body or remains found about 81 feet from scene of explosion |

| Joseph Pearce | 25 years | body or remains found about 81 feet from scene of explosion |

| Robert Weeks | 30 years | body or remains found about 111 feet from scene of explosion |

| Edward Morgan | 32 years | body or remains found about 81 feet from scene of explosion |

| Evan Davies | 41 years | body or remains found about 111 feet from scene of explosion |

| John Osbourne | 25 years | body or remains found about 81 feet from scene of explosion |

| George Moore | 20 years | body or remains found about 81 feet from scene of explosion |

| David Hitchins | unknown | body or remains found about 111 feet from scene of explosion |

| Morgan Jones | 19 years | body or remains found about 111 feet from scene of explosion |

| Richard Parsons | 29 years | body or remains found opposite scene of explosion |

| James Oates | unknown | body or remains found about 81 feet from scene of explosion |

| John Clements | 13 years | body or remains found opposite scene of explosion |

Two of the deceased, Richard Parsons and the boy Clements, were blown to atoms; some small fragments only of their bodies having been recovered, and these fragments were found in the immediate neighbourhood of the manhole where the explosion had occurred. With regard to the other men, some of them, as Bartle, Moore, and Quick, were more or less externally injured, but the others do not appear to have exhibited any marked injury, and were considered by the doctors who gave evidence to have been killed by the shock to the nervous system and the cooperation of poisonous gases – i.e. chiefly carbonic acid. A number of other men who were working further in the tunnel (see Plan) escaped injury. The position and details of the manhole at which the explosion occurred, the structural damage effected by the explosion, and the spots at which the bodies were found and at which the injured and uninjured men were working, are shown on the accompanying plan, which is reduced from a tracing which was produced on behalf of the Company at the inquest, and of which a copy was given to me for the purpose of my inquiry. I desire here to take the opportunity of stating that I received from Mr Lean, the resident engineer of the Company, every assistance and facility in carrying out my investigation, and also that the servants of the Company whom I examined replied readily to my inquiries.

After the accident had occurred, William Elliott, the foreman at the Cymmer end of the tunnel, and others, were prompt in removing the injured men, and Elliott especially seems to have displayed great presence of mind and gallantry. Immediately on the accident occurring he gave instructions to the engineman to keep up a strong blast of fresh air into the tunnel; and he himself worked at the removal of the bodies and of the injured men until he was overpowered and rendered insensible by the noxious gases which the explosion of the dynamite had produced.

Arrangements of the Company for the storage and supply of explosives

Proceeding to examine more particularly into the circumstances and cause of this lamentable explosion, the most fatal that has occurred in this country since the Stowmarket Gun-cotton Explosion in 1871, it appears that the work which was being carried on by the Company involved the use of a considerable quantity of explosive. Both gunpowder and dynamite were employed for the purpose; and at the time of the accident the Company also had some Cotton powder in their possession. Two magazines existed for the storage of the explosives, both being at the Maesteg side of the tunnel and distant over a mile from the Cymmer end. One of these magazines is used for the storage of dynamite; the other is used for the storage of gunpowder and cotton powder. The two magazines form separate buildings, more than 100 yards apart. The dynamite magazine existed in virtue of a special license No. 322, granted under the Nitro-Glycerine Act, 1869 (32 & 33 Vict. c. 113), and dated 25th August 1875. This license being limited in duration to 12 months, holds good (in virtue of Section 52 of the Explosives Act,) until it runs out in August next, consequently the Company held their dynamite not in virtue of any licence under the existing Explosives Act, but in virtue of the unexpired license specified above.

The gunpowder magazine does not appear to have been covered by any license under the old Act, or by any license or registration under the new Act, and the storing of cotton powder (exceeding the amount which may be kept for private use and not for sale) without license or registration, was also illegal.

The question of illegality in regard to the storage and use of the explosives will, however, be more fully considered further on.

The practice appears to have been for the foremen respectively in charge of the two ends of the tunnel to draw supplies of explosive for their use from the magazine. At the Maesteg end of the tunnel, the foreman generally drew only a small quantity of explosive, about enough for 12 hours working, and this was deposited in a wooden box a little way within the tunnel, a packet being brought from the box to a little wooden shed outside, for the purpose of fitting the detonators and fuse for firing. I am not strictly concerned with this end of the tunnel, except in so far as the practice there bears upon the practice at the other end; but I cannot refrain from noticing the almost entire absence of precautions which I observed there. The box where the packages of dynamite are placed for use, contained, at the time of my visit, candles, fuse, old iron and rubbish and dirt of various descriptions; while the wooden shed, in which the charges were made up was a sort of general store, full of iron, spades, pickaxes, and other implements. There was also a stove in it, but this I was assured is never used.

It is clear, however, that at the Maesteg end of the tunnel, the precautions for preventing accidents by explosion were at a minimum; and no attempt seems to have been made by the issue of suitable instructions to enforce care and caution. Turning to the Cymmer end of the tunnel, it appears that the manhole where the explosion occurred had been specially appropriated to the reception of the dynamite as it was received from the magazine at the Maesteg end; and it was fitted with a door and lock. The detonators and fuse were also kept here, the former being placed on a small shelf made for the purpose in the upper part of the manhole. Elliott, the foreman at this end, states that it was an instruction to the men to prepare their charges not at the manhole where the dynamite was kept, but at another manhole 40 feet further in the tunnel. This instruction, it was stated, as also the directions for the preparation of the manhole where the stock of explosive was kept, had emanated from Mr Lean the engineer.

The powder which was drawn from the magazine appears to have been kept in a separate place, some of it being in a manhole 80 feet nearer the entrance of the tunnel than the dynamite manhole.

The next question is, what quantity of explosive was kept in the manhole; and what were the precautions enjoined or observed with regard to it.

The former of these points is of importance, not merely as bearing upon the loss of life and extent of damage produced by this explosion, but as affecting the question of the legality of the presence of a quantity of dynamite within the tunnel. The other point is of importance in regard to the light which it may throw upon the cause of the accident, and in its relation to the question of whether blame attaches to the Company or their responsible officers or servants for this explosion.

With regard to the quantity of explosive kept in the tunnel, there is, I think, no doubt that the quantity of dynamite actually present in the manhole at the time of the explosion was 150lbs. An issue of 200lbs of dynamite had been made from the magazine by Butland, the storekeeper, on the 18th April; and of this quantity, Elliott states 50lbs and no more had been used up to the time of the accident. Elliott spoke positively on this point. There were also in the manhole about 10lbs of cotton powder, some detonators and fuse. The whole of these were exploded or destroyed by the explosion.

It is clear, therefore, from the above that there had been placed in the manhole on the 18th a quantity of dynamite sufficient for several days consumption; because while the quantity so deposited was 200lbs, it appears that the actual consumption from the 18th to the 21st (3 days) only equalled 50lbs. This fact it will be my duty to comment upon more closely hereafter.

As regards the precautions taken to prevent accidents, even if we assume that the place was intended only as a place of deposit for dynamite, those precautions appear to have been very much less stringent than is necessary to afford even a reasonable measure of security against accidents.

The manhole had, it is true, a locked door; and the key was held by the two responsible foremen, Elliott and Bartle. But they were in the habit of giving the key to certain of the workmen for the purpose of fetching what dynamite they wanted; these men were not forbidden to use a naked candle in removing the dynamite, nor, indeed, do they appear to have been enjoined or required to exercise any more care than if they had been handling an inexplosive substance. Detonators, as I have stated, were also kept in the place; and the manhole itself was not lined or in any way fitted as a place in which a quantity of explosive was habitually deposited most certainly should have been. And, as a matter of fact, the manhole cannot be regarded as merely a place of deposit. It was also, as it appears, commonly used for the preparation of the charges, by the fitting together of the detonators, fuse, and dynamite. I have stated that this was contrary to instructions; but Elliott himself admitted frankly that this rule had to his knowledge been frequently disregarded, and that such disregard of a rule, which he considered an important one, he had not visited with more than a verbal reprimand. He had himself, he says, “several times” seen Richard Parsons preparing the primers at the dynamite manhole. He had seen him doing so with a naked candle sticking against the side of the wall outside the manhole about a foot or six inches from it; he had even seen him smoking while so engaged, and he knew, he tells us, that this was dangerous. But it never seems to have occurred to him that it was his duty to do more than reprimand the man; he had never even reported such dangerous disregard of instructions to Mr Lean, nor had he taken the obvious precaution of refusing to allow this careless man the use of the key of the place. On the contrary, he allows Parsons to go again and again to the place; he again and again sees him doing what he knows was dangerous and directly contrary to orders; but he is satisfied on each occasion, with merely cautioning the man not to do it again.

Cause of explosion

With regard to the cause of this explosion, there is evidence that Parsons at the time it occurred was again doing that which Elliott said he had before, and, in defiance of orders, and in disregard of warnings and reprimands, done “several times” that is to say, he was engaged in preparing his primers at the manhole in which the supply of dynamite was deposited. William Lewis, a collier by trade, happened to have gone into the tunnel a few minutes (he says about five or ten minutes at the outside) before the explosion. As he passed the manhole he observed Parsons sitting on the sill of the manhole, and he had some conversation with him. Parsons was engaged in making up his charges, he had the detonators and fuse to his left hand, and immediately above the little accumulation of explosives, and about 6in from the side of the manhole, he had his naked candle stuck against the wall in the usual way by a piece of clay. It is significant of the general disregard of precautions which prevailed, that Lewis should have selected a man engaged on this work as the person from whom he could most conveniently obtain a light for his candle; and it is significant also of Parsons’ general recklessness, that he should not only have been ready to give him a light, but that while so engaged, he should have invited his particular attention to the detonators and other explosive material lying beside him. But this, Lewis states, is what passed; and when the conversation had ceased, Lewis passed on up the tunnel, after which, in a few minutes the explosion occurred. The fact that the remains of Parsons, blown almost to pieces, were found close to the manhole, tends to show that he was, at the time of the explosion, still engaged upon the work which had occupied him when Lewis passed. Such being the case, it really seems unnecessary to have recourse to recondite suggestions to explain the cause of this terrible explosion. I am not aware that it has ever been seriously suggested that the explosion was the result of spontaneous ignition; but, as this theory is rather a favourite one on such occasions, I thought it desirable to submit to Dr Dupre a sample of the dynamite from the same batch as that which exploded (taken from the magazine at the Maesteg end) for chemical examination. That gentleman’s report shows that the dynamite was of satisfactory quality, and free from any indications of destructive chemical action, or of the presence of any elements which would justify suspicion in this direction.

We are then left with our choice of the following possible explanations –

1: That, through some carelessness or clumsiness, Parsons exploded a detonator as he was fitting a fuse into it, or as he was fixing it in a primer

2: That a spark was communicated in some way to one or other of the explosives present

3: That the explosion was produced by a blow

4: That the candle fell on to and fired one or other of the explosives, thereby causing the explosion of the whole.

As regards the first possible cause, it is not impossible that the explosion may have proceeded from it, but it is certainly the most improbable of the four possible explanations enumerated above.

As regards the second possible cause, I ascertained by experiment not only that a spark can readily be struck with a piece of steel against the “Pennant” stone (a hard sandstone) in which the manhole was excavated, but that even two pieces of the stone itself struck smartly together are liable to give a spark. It is certain that the boy Clements was standing at or near the manhole at the time of the explosion; for he was blown to pieces, and the few remains of his body which were recovered (consisting only of his fingers) were found close to the spot. It is also certain that he had with him a steel drill 4ft long and 1¼in diameter, which was recovered after the accident doubled up in a serpentine shape, showing that it had been subjected to some great violence. There is no doubt that this drill would have been capable of striking a spark which might have fired the dynamite, or cotton powder, or the fuse.

Or, thirdly, the same drill would have been capable of exploding the dynamite by a blow. Dr Dupre’s report shows that dynamite of this quality can be exploded by a 1lb steel weight falling on to it a height of 18 inches. Or, the drill falling into the detonators might have produced an explosion; and Mr Lean holds strongly to the opinion that the accident was caused in this way.

It is, of course, impossible to say that it was not so caused, but I venture to think that the falling of a candle (either that belonging to Parsons, or that carried by the boy) on to the little pile of detonators, fuse, and dynamite, is by far the most probable of the four suggested causes. It was urged by Mr Lean, 1st, that had a candle fallen it would at once have been noticed, and Parsons and Clements would have had time to get away from the spot; but, as Elliott pointed out, had only one of the two candles present fallen, its fall might readily have escaped observation for the moment of time which would suffice to produce the ignition and resulting explosion; indeed, it is quite possible that a spark only may have fallen from the candle and not the candle itself.

2nd, Mr Lean observed that had the explosion been produced by the ignition of the dynamite or fuse, the noise of the burning material would almost certainly have attracted Parsons’ and the boy’s attention, and they would naturally have fled. But to this it may be replied that the noise produced by the burning of a small portion of dynamite is scarcely perceptible until the ignition has proceeded to some extent, and assuming that Parsons (who it must be recollected had been at work for some little time) had by him a few primers with the detonators fitted into them, a spark falling on to one of these would suffice to establish ignition, and, from an experiment which I have made, I conclude that this ignition of the dynamite might easily have produced the explosion of the detonator inserted in it before the sound of the burning was perceived; and, in the next place, an explosion produced by this means would have followed almost immediately on the ignition of a primer in which it may be assumed a detonator was fixed. Persons who have not actually made the experiment can hardly be aware of the silent rapidity with which the burning of a portion of ignited dynamite proceeds. And this observation holds good also with regard to gun-cotton. I am satisfied from my experiments that had a primer of dynamite (or gun-cotton) fitted with a detonator become ignited, it would scarcely have been possible for any person who might be close by to have effected their escape before the explosion which would be the necessary consequence of such ignition took place. I may add that I have also ascertained by actual experiment that a lighted candle falling on to dynamite almost instantly ignites it. Considering, therefore, that it is established that there existed all the elements for the production of an explosion in this way – the naked candle stuck against the wall by means of clay (to say nothing of the candle probably in the boy’s hand), the dynamite and the detonators, and almost certainly some primers already fitted with detonators, it seems unnecessary to have recourse to such explanations as the falling of a steel drill, or the accidental explosion of detonators to account for the explosion. There can, I should say, be very little reasonable doubt that the explosion was produced by the falling of a candle (or a spark therefrom) on to some of the explosive present, probably on to a primer of dynamite with detonator fixed, and that the resulting explosion extended to the whole of the explosives within the manhole.

That the large quantity of dynamite present increased the loss of life, I have no doubt. It will be observed that the large proportion of the men who were killed were working at a distance of from 80 to 111 feet from the scene of the explosion, and it is further noticeable that of the men working at this distance two escaped with their lives. I am accordingly led to the conclusion that had the quantity of dynamite present been very much less than that which actually exploded, the lives of the whole of the 10 men who were working at these distances from the scene of the explosion would most probably have been saved.

Consideration of the question as to the blame attaching to the Company or their servants

And this brings me to the concluding consideration –

What blame attaches to the Company or their servants for this sad explosion and loss of life?

The coroner’s jury, after about an hour’s deliberation, returned the following verdict: “That the deceased died from suffocation and shock, the result of an explosion of dynamite, but how caused there is not sufficient evidence to show.” I feel constrained to say that this verdict falls very far short of the meeting the justice of the case; and I must profess my surprise that the jury did not consider that the evidence which was laid before them at the inquest called for a more decided verdict, or at least made imperative some strong expression of opinion as to the general manner in which that part of the business of the Company which was connected with the storage and management of explosives was shown to have been carried on.

I conceive it to be my duty, at any rate, to point out that the Company appear not only to have been guilty of certain violations of the law, one of which I cannot doubt contributed to augment the loss of life resulting from this accident; but that they are also chargeable with an amount of carelessness and negligence in the management of the explosives kept and used by them which calls for a strong expression of censure and fixes on them a most serious responsibility in connection with this accident.

As regards the illegalities which I conceive were committed, it appears –

1st. That the Company at the time of the accident were storing gunpowder and cotton powder without any license or authority. I have stated that they possessed a gunpowder magazine, and it appears from a return furnished to me by the Company of the issues of explosive to the Cymmer end of the tunnel, that the consumption of powder was considerable. It appears therefrom that there were constant issues of 2cwt of gunpowder at a time. Thus, in January, there were six such issues, making 12cwt; in February there were four such issues, making 8cwt; in March there was one issue of 2cwt; and in April (up to the 21st) there were three such issues, or 6cwt. Thus the total issues of gunpowder from 1st January to 21st April amounted to 28cwt. Under the Explosives Act, which came into operation on the 1st January last, no person may keep more than 30lbs of gunpowder without a license or under registration, and then only provided it is kept for private use and not for sale. It is clear, therefore, that (not to go further back than the 1st January) the Company had been illegally storing gunpowder. They had also, it appears, been illegally storing gun-cotton (or “cotton powder”), for on the 17th April there was an issue to the Cymmer end of 56lbs of “patent gun-cotton” and “100 cartridges compressed ditto”. Of this material the Explosives Act allows only 15lbs to be kept (for private use and not for sale) without license or registration (Order in Council No.8).

With regard to this, however, Mr Lean laid some stress on the fact that the Company had, prior to 31st March, made application for a store license to cover the storage of “Mixed Explosives”, which license they have failed to obtain owing to the proposed site not being strictly in accordance with the provisions of the Order in Council relating to Stores. But it is proper to point out that the keeping of this gunpowder without a license had not only constituted an illegality since 1st January 1876, but was illegal under the old Act which expired at that date (see 23 & 24 Vict. c. 139, sec. XVIII.), and the mere fact of applying for a license about the end of March would not excuse the previous illegality, nor cover the continued storage of the explosive preceding the grant of such license, or after it had failed to be obtained.

2nd. But a more serious illegality, in my judgment, consisted in the storing of quantities of dynamite in the manhole at the Cymmer end of the tunnel. A reference to the license held by the Company shows that condition 3 directs that Nitro-glycerine preparations stored in pursuance of this license shall – “not be stored anywhere than in a certain magazine well and substantially built of brick or stone, or excavated in solid rock, earth, or mine refuse, and lined throughout with wood, and situated at Blaen Llynvi, near Maesteg, in the parish of Llangonoyd, in the county of Glamorgan”; and condition 11 directs as follows – “Nitro-glycerine preparations stored under this license shall not be used except by the licensee or persons in his immediate employ; and shall not be sold or served out except to persons in the immediate employ of the licensee for the immediate use of such persons on work authorised by the licensee.”

Now it has been shown that a quantity of dynamite amounting to 200lbs had been deposited in the manhole in the tunnel, which was not the place authorised by the license for the storage of the same, on the 18th April, and that at the time of the accident there remained of this amount 150lbs. If this constituted a “storage” of dynamite it was a violation of the third condition of the license above recited, while if the issue of the 18th April was in excess of what was necessary for immediate use, the eleventh condition of the license had also been violated. I venture to express my opinion that there was a violation of both those conditions. There is, it is true, no actual limitation of time assigned in the Nitro-glycerine Act or in the license as the limit beyond which keeping constitutes “storage”; but, taken in conjunction with the eleventh condition of the license, it must, I think, be clear that where dynamite is kept in excess of what is required for “immediate use” there is a “storage” of the same. This brings me to the question – What is immediate use? The resident engineer Mr Lean, who naturally in the interests of the Company would be disposed to assign a liberal interpretation to this expression, appeared to consider that “immediate use” meant about a day’s (24 hours) consumption.

Elliott stated that he had received verbal instructions from Mr Lean not to get more than two boxes (=100lbs in all) at one time. This, at the rate of consumption which had obtained up to the date of the accident, would generally represent four or more days consumption. Mr Lean, however, states that he does not recollect giving Elliott these instructions, and thinks it improbable that he would have given an order for any definite limit of quantity without regard to the actual consumption. But be this as it may, it is quite clear that, as a matter of fact, no correspondence between the quantity required for “immediate use” and the quantity actually issued was observed on the occasion of the last issue or on former occasions.

An analysis of the return gives the following results –

January – Total issues between 3rd January and 3rd February, 650lbs. If we assume that the consumption proceeded at the same rate, we have for the 31 days an average consumption of about 21lbs a day. But in no case were the issues less than 50lbs, or two days consumption, and in one case (the 14th), 100lbs was issued. There were in the month, 11 issues of 50lbs, = over 2 days each, and 1 issue of 100lbs, = nearly five days.

February – Total issues and (assumed) consumption from 3rd February to 1st March, 750lbs, = average consumption for the 26 days, 29lbs per diem. But the actual issues were –

7 of 50lbs = over 1½ days each

2 of 100lbs = about 3½ days each

1 of 200lbs = about 7 days

March – From 1st March to 4th April, issues and (assumed) consumption, 550lbs, making an average consumption for the 34 days of 16lbs a day. But the whole of this amount was served out in only five issues, being –

1 of 30lbs = about 1½ days

4 of 100lbs = about 6½ days each

April – Issues from 4th to 21st, 550lbs. Of this 150lbs was destroyed by the explosion, leaving 400lbs expended between the 4th and 21st, and giving an average consumption for the 17 days of 22lbs a day. The issues during this month were –

1 of 50lbs = 2 days consumption

3 of 100lbs = 4 days consumption

1 of 200lbs = 8 days consumption

I do not lose sight of the fact that this mode of exhibiting the want of correspondence between the issues and the quantities required for “immediate use” is open to the objection that being based upon the “average” rate of consumption it takes no account of the occasionally heavy expenditures of dynamite, or of the days when there was no such expenditure at all. It may be represented, for example, that although 100lbs was issued on the 14th January when the average consumption was only 21lbs a day, there is nothing to show that the whole of that 100 lbs was not, in fact, used on the 14th or 15th. But this argument, if it be admitted, includes also the admission that the consumption was exceedingly variable, and subject to no very reliable rule of averages, and it follows, therefore, that the storekeeper, in the absence of definite information as to the actual consumption or immediate requirements, could not possibly have adjusted his issues to the real requirements for “immediate use”. In the absence of any such information he would have nothing whatever to go upon but his calculation as to the rate at which the dynamite was demanded, and at which, judging from the frequency or infrequency of these demands, its use was proceeding; and the above tables at any rate show that if he in fact proceeded upon this method of calculation he certainly made no attempt to observe any relation between his issues and the amount apparently required for immediate use, seeing that he actually made his issues in quantities varying from one and a half to eight days average consumption. Had the storekeeper then anything else to guide him? It appears that he had not. It was the practice of the foreman, Elliott, when he wanted dynamite, to make a requisition on a form provided in a book; but it was not his practice to specify the amount required, nor had the storekeeper, whose magazine was distant about a mile (over rough mountain road) from the Cymmer end, any other opportunity of ascertaining with any sort of accuracy what was being actually used. And as a matter of fact it appeared from my examination of the storekeeper that he was even ignorant of the particular condition of the license which required the issues to be thus regulated.

It can hardly be successfully contended that a storekeeper who was not only ignorant of the actual quantities required for “immediate use”, but also of any obligation limiting the issues in this way, was in a position or likely to observe this condition of the license, and it is not therefore to be wondered at that an examination of the issue book discloses on the face of it an entire absence of any observance accidental or designed of this condition.

Still, despite the probability, almost certainty, that this condition must under the circumstances have failed to be observed, and despite its apparent non-observance throughout the three and a half months preceding the explosion, as ascertained by the method of computation adopted above, I deemed necessary to examine a little closer and to inform myself whether there actually was, on the particular occasion in question, a non-observance of this rule. The storekeeper’s book shows that there was an issue to the Cymmer end, on the 18th April, of 200lbs of dynamite. Elliott stated that on receiving this large amount he was at a loss what to do with it, and would have sent some of it back, but he considered he had no authority to do so. There had been nothing in Elliott’s requisition to suggest the sending of this large quantity. It is true there had been a slight delay in the obtaining of dynamite from the agent at Cardiff, and there was also the fact that the chairman of the Company (Major Beaumont) was known to the storekeeper to be present and carrying out experiments with new drills, and there was thus on his mind an impression that the stock had run out, and that the occasion was one when probably an extra supply would be useful. As a matter of fact both these surmises were incorrect, for there still remained (Elliott says) 50lbs of dynamite when the new supply was received, and there was in fact no increase whatever in the actual rate of consumption for that month.

These circumstances alone, show how impossible it was for a storekeeper, without definite instructions and a proper system, to have observed this important condition. Moreover, the license leaves no room for guesses and conjectures of this sort.

It expressly prohibits the issue of larger quantities than are required for immediate use; not quantities larger than the storekeeper or other person may consider or conjecture to be necessary, but quantities not exceeding what actually is necessary.

Applying this test, we find that while 200lbs were issued on the 18th, no less than 150lbs of that amount was unexpended on the evening of the 21st. This circumstance, quite apart from the other considerations which I have urged, seems to establish clearly a serious violation on this particular occasion of a most important condition of the license; one, moreover, to which, as I have shown, the storekeeper’s attention had not been specially directed by the Company, of which, indeed, it appeared that he was in fact ignorant, and one, finally, the neglect of which contributed, I do not doubt, to a large increase in the number of deaths resulting from this most serious explosion.

I observed one or two minor illegalities in the magazine, e.g. it was not wholly lined with wood, and it was not wholly free from the presence of iron; but on these points it is not necessary particularly to insist. The substantial illegality was that which I have endeavoured to bring out into prominence above, viz. the illegal storage in the tunnel of a quantity of dynamite in excess of what was required for immediate use.

Negligence of the company and their servants with regards to the management of explosives

But it is still my duty to make some observations on the negligence which is shown to have prevailed with regard to the keeping and handling of the dynamite.

I have already mentioned the laxity which prevailed even subsequent to the explosion, and up to the time of my visit, at the Maesteg end of the tunnel, a laxity which is not to be excused by the fact that the quantity of explosive was small, for it was certainly not so small that fatal consequences might not have ensued from its explosion. But at the Cymmer end with which I am more particularly concerned and where the quantity kept was sufficiently large, as we unfortunately know only too certainly, to cause the deaths of many persons, the absence of adequate precautions was not less conspicuous. Indeed, if we except the facts that the manhole where the dynamite was stored (in quantities far exceeding what was necessary) was provided with a locked, door, and that the men had been instructed not to prepare their charges at this spot – an instruction which it plainly appears there was no real attempt to enforce – it may be said that no precautions whatever were taken.

The foreman who was charged with the receipt and custody of the dynamite had neither received nor issued any written instructions with regard to its management; he was even doubtful, it seems, whether he would be justified when he received an unduly large supply (as he did on the 18th April) in sending some of it back, and as a matter of fact he did not venture to take the responsibility of doing so, and accordingly stowed it all away for want of a better place in the manhole; a suggestion which Elliott says he had made to Mr Lean that a small supplementary magazine should be provided outside the tunnel was not adopted; the manhole beyond being provided with a door and lock was not fitted in any way as even a place of temporary deposit for explosive should be, whether the explosive so deposited be in large or small quantities; the detonators were kept inside the manhole with the dynamite; the whole business of the place was permitted to be carried on by the light of naked candles; smoking, which in theory was prohibited, could, as it appears, be indulged in in the manhole with impunity; while even repeated disregard of the orders which had been given against preparing the charges at this manhole entailed upon the offenders no more serious consequences than a verbal reprimand.

It is not surprising that such general laxity and carelessness should ultimately have resulted in a disaster; indeed the really surprising thing would have been the absence of such a result; and I consider that the Company in permitting such a state of things to exist on their works incurred a most serious responsibility, and have laid themselves open to very grave censure. The case is, in my judgment, further aggravated by the considerations, 1st – That the responsible officers of the Company were cognisant of the habitual carelessness of their workmen in their dealings with explosives, a carelessness of which in the case of Parsons the foreman Elliott had repeated and ample ocular evidence; 2nd – That they could not plead ignorance of the sort of precautions which should have been observed because the detailed conditions of their dynamite license furnished a useful and sufficiently precise guide on this point. The observance in the manhole of the precautions enjoined in conditions 6 to 10 of this license would probably have averted this disaster, and I quite fail to follow an argument or excuse put forth by Mr Lean, that while these precautions were no doubt proper to be observed where the amount exceeded 150lbs or 200lbs they were unnecessary in the case of smaller quantities; indeed, a more emphatic contradiction of the soundness of Mr Lean’s view that there was no objection to detonators being kept with the dynamite when the latter did not exceed 150lbs could not have been furnished than was furnished by the unfortunate fact that this particular amount of dynamite had sufficed (through the agency in all probability of a single detonator) to kill 13 persons, and it must be a matter of surprise and regret that Mr Lean should have ventured to offer this argument in face of the damaging refutation which this explosion afforded. Nor did Mr Lean’s argument in favour of the use of naked candles appear to me more convincing. He urged that the light given by a lamp is inferior to that given by a candle, and that consequently with a lamp there would have been a greater temptation to bring it into dangerous proximity to the explosive. But it appeared on cross-examination that Mr Lean’s conception of the relative illuminating power of candles and lamps rested upon no substantial basis. He had not, he said, taken any steps to ascertain whether a safe and efficient lamp for magazine use could be obtained, notwithstanding that the 8th condition of his dynamite license distinctly indicated the existence of such a lamp. Had he taken any trouble on the subject, he would have discovered that two patterns of lamps had been approved by me on behalf of the Secretary of State, and that the illuminating power of either of them was vastly superior to that of the common tallow candles actually employed. He would also have found that these lamps might be brought into even close proximity to an explosive without danger. In fact, he would have found that his argument on this point was worthless. Further, it appears to me that the grounds upon which Mr Lean stated that he had declined to adopt the suggestion made by Elliott, that a supplementary magazine should be provided outside the tunnel for the storage of the supplies of dynamite as received from the Maesteg end are wholly untenable. He said, that to have adopted this prudent suggestion would have entailed the carriage of prepared charges of dynamite fitted with fuse and detonator from such magazine into the tunnel at a risk to the persons working outside and to the huts and workshops, and that as dynamite is not dangerous until it is fitted to the detonator the nett result of this arrangement would have been an increase of risk. But even if the statement that dynamite is not dangerous until it is fitted to a detonator were correct, which it certainly is not, the result suggested by Mr Lean would not necessarily have followed; for it would, of course, have been open to the Company to require the detonators to be fitted as required for use in the tunnel, such small quantities only being sent from the supplementary magazine into the tunnel as might be actually required for immediate use. Moreover, by storing the stock of dynamite in the tunnel instead of outside, two journeys were in fact necessitated instead of one, for all dynamite so taken in had to be brought out again in quantities sufficient for immediate use, to be softened by the application of heat, and when so softened taken back again. Had the stock been kept in a supplementary magazine, the required quantities might have been taken out therefrom, softened at the place appointed for the purpose, and when softened carried on into the tunnel, there to be primed and used.

In short, the arguments by which it was sought to excuse the practices or omissions of the Company were, to my mind, the reverse of satisfactory, and in discharge of the duty imposed upon me by the 4th sub-section of section 66 of the Act, of making such observations on the evidence or any matters arising out of the inquiry which I may think right, I feel constrained to express my opinion that these arguments must be regarded rather as excuses put forward after the occurrence for what they are worth, than as considerations which had seriously influenced the Company and their servants with regard to the course which they had adopted, or with regard to the precautions which they had omitted to observe.

When all has been said, the conclusion appears inevitable that serious blame attaches to the Company and their servants for the dangerous negligence which is shown to have prevailed at these works in regard to the keeping and handling of explosives.

To apportion the blame in regard to this negligence is not easy. Primarily I suppose the Company must be held responsible for the acts or omissions of their servants, and I do not think this responsibility can be considered to be discharged by the fact that, in practice, the working management was vested in Mr Lean. It was surely the duty of the Company, as it is of everybody carrying on operations which involve risk of accident, to satisfy themselves that adequate precautions have been adopted for the prevention of accidents. Had the Company made any inquiry of this sort, I cannot doubt that they must have seen reason, as they can hardly fail to see reason now, for dissatisfaction with the arrangements. The professional qualifications of the chairman (Major Beaumont, RE) and his experience in connection with explosives, would at once have suggested to him that the arrangements adopted were not such as to afford any reasonable security against a serious accident.

The actual working arrangements were, however, in the hands of Mr Lean, the resident engineer, and it does appear to me that this gentleman is seriously to blame for the state of things which prevailed. It was, in my opinion, his duty to have taken steps to secure the strict observance of the conditions of the license and the adoption of proper measures of precaution; but Mr Lean appears to have tacitly delegated his functions to the storekeeper and the foremen, and this without taking any steps to direct their special attention to the particular points affecting their respective duties. Butland was left to find out for himself how much dynamite he should issue, and this, as we have seen, he wholly failed to discover; and the foremen were left to take such precautions as seemed to them proper, and these, it has been shown, were culpably inadequate; so, in the end, we find an excessive quantity of dynamite being issued and the keys of the manhole in which it was kept entrusted to a man (Parsons), whom the foreman, Elliott, knew to be reckless and in the habit of disobeying such elementary orders as had been issued with a view to the prevention of accident. There was thus, as it appears to me, a general failure of duty and censurable negligence on the part of all concerned, beginning with the Company, continuing with Mr Lean, Butland (the storekeeper), and Elliott, and ending with Parsons, and to the failure of duty and negligence of this last-named man in the careless and improper making up of the charges at the manhole, the explosion, as I have shown, may be immediately ascribed, while the large resulting loss of life was no doubt due to the direct violation of a condition of the license and the illegal presence of a quantity of dynamite largely in excess of what was required for “immediate use”.

V D Majendie, Major RA, HM’s Inspector of Explosives