Local newspapers tell the story of a double fatality A reckless descent

Local newspapers tell the story of a double fatality A reckless descent

Shocking accident at Clayton

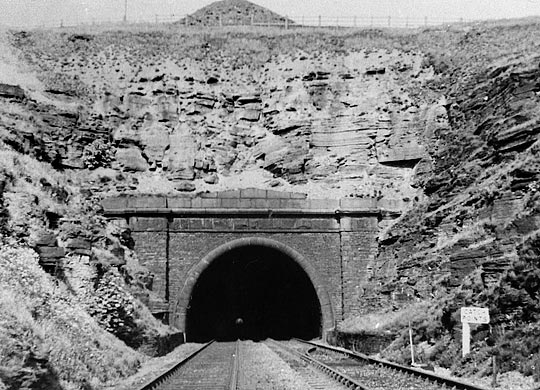

On the line of the Great Northern Railway, from Halifax to Bradford, and thence to Thornton, there are two very heavy tunnels in the course of construction, one under Clayton Heights, about 1,000 yards in length, and that under Queensbury, about 2,000 yards long. Along the line of the tunnel first named, four shafts have been sunk so that headings can be driven simultaneously from eight different points, and the works connected with these headings are carried on night and day almost without cessation.

Over the shaft at which the accident occurred, large timber scaffolding, or head gear has been fixed, surmounted by a pulley from four to five feet wide, and by means of this the rubbish from below is raised to the top of the shaft; and at a few yards distant from the mouth of the shaft an engine for winding up the tubs of debris, and pumping water, has been planted.

There are usually eleven men in each shift at the bottom of the shaft, and at six o’clock on Wednesday morning, Henry Hickman, one of the sub-contractors, gave orders for the day shift to go down and relieve the night men, and accordingly four of them got into the tub or cage to descent. Before this could be done, however, it was necessary that the cage should be raised a little, in order that the “lorry” might be drawn back a little from underneath to allow the skep and the men to descend.

When the lorry was withdrawn, the order was given to lower, but from whatever cause, the engine had not been reversed, and instead of being lowered, the skep was drawn to the top of the head gear and went backwards over the pulley, the result being that one of the men, Thomas Coates, Hickman’s brother-in-law, fell to the bottom of the shaft, a depth of 35 yards, was horribly crushed and died in five minutes. The other three men fell to the ground about five yards from the pit mouth, with the skep after them, and were all seriously injured as they had fallen nearly 40 feet. The names of the three men who then so narrowly escaped were William Elliott of Queensbury, whose internal injuries were such as to preclude any hope of recovery, James Spillbury from Shelf, and William Williams. The third was the least injured of any, but still suffered from dislocation of the hip and a few bruises. They were all conveyed as soon as possible to the Infirmary in this town, and arrived there about half-past eight o’clock; and from the first no hope could be held out of Elliott’s recovery as he was suffering from a fractured pelvis and other severe internal injuries, while Spillbury had sustained concussion of the brain, and he was then also in great danger, though his recovery was not despaired of.

The body of Coates was removed to the Royal Hotel, Clayton, where on Thursday afternoon an inquest was opened before Mr Barstow, deputy coroner.

The wife of the deceased, Tamar Ann Coates, said that her late husband was twenty-seven years of age, and lived at Clayton Heights. He was working as a filler in the employ of her two brothers, who were sub-contractors under Messrs Benton and Woodiwiss, the contractor for the railway.

Mr John Fawthrop, surgeon, Queensbury, said he had seen the body of the deceased at the Royal Hotel, at about eight o’clock on the morning of the accident, and found beside a lacerated wound on the chin and sundry bruises and scratches, a fracture of both thighs, and concussion of the brain, the latter having caused death.

James Bright, banksman at No.4 shaft on the tunnel, said when the accident occurred he was on the bank top, and saw Coates, Elliott and two other men get into the skep, then resting on the lorry which runs over the mouth of the shaft. Witness gave four signal “raps” which meant that the engineman was to raise the skep a few feet, in other that the lorry might be drawn from underneath them, and the instructions were obeyed. He then gave two raps, meaning to lower the skep to the bottom of the shaft, but instead of that the skep went right up the pulley on top of the head-gearing, and when he gave one rap to stop the engine, the skep was drawn right over the pulley, and fell on the ground between the shaft and the engine-house. Deceased either jumped or was thrown out, and fell right down the shaft. There were two men in charge of the engine, one of whom worked the day and the other the night shift, namely William Francis Taylor, and Edward Keats, but he could not say which of them was on duty at the time. Keats ought to have been on until six o’clock, and it then wanted a minute or two to six, it being very dark at the time. Witness had heard that a skep had been pulled over on Saturday.

Mark Radford, a miner who was working in the pit at the time, picked up the deceased. He was not dead, but died in a few minutes. Witness brought his body to the top of the shaft.

Henry Hickman, sub-contractor, deposed that he was standing near the pit mouth and saw the accident happen. He heard the raps given to raise the lorry with the four men in it, and it was lifted a few feet and then stopped half a minute, and then it was drawn up to the pulley. Immediately after the accident Taylor ran out of the engine-house and came to the top of the shaft, when he asked witness, “Oh Harry, who’s down the shaft?” and he replied “Tom Coates”. Then Taylor said again, “That ____ (meaning Keats) has left a trap for me, he left the engine in motion,” and then Taylor was as white as a sheet. Keats was away half an hour from the time the accident happened.

Wilkinson Andrews, aged seventeen, stoker and cleaner for Taylor, said he was at the engine-house five minutes before the accident happened, and the engine was not then in motion. No one was on the driver’s seat at the time, and as it wanted five minutes to the time he turned round and sat down, and the next he heard was some shouting outside on the bank. Witness then saw the rope coming slack on the drum, and immediately after Jacob Wright cried out, “You’ve pulled a poor fellow into the pit.” Taylor, Hoyle and Keats then ran out, and witness stopped the engine which was then running the rope off the drum. He could not tell who set on the engine. All that Taylor had said to witness since the accident was, “It was cruel of Ned.” Since then, witness had not spoken to Keats.

Henry Hoyle, aged thirteen, stoker for Keats, said that Keats was going to the seat, when Taylor said, “Come away” and Keats then put some oil on his hands, and was drying them, when the accident occurred. Witness saw Taylor go to the seat as soon as Keats left it, and the engine was then standing, and continued so for fully a minute after Taylor got onto the seat. When Taylor started it, he put full steam on, and must have thought the skep was at the bottom.

George Richardson, a labourer on the line, said he was passing the door of the engine-house about five minutes before the accident happened, and he then saw Taylor on the driver’s seat. Witness went into the engine-house some time afterwards, and heard Taylor say that he would take his “dying oath” that he was not on the seat at all.

No further evidence was then called and the inquiry was left in this unsatisfactory state – involving something very like recrimination between the two engine drivers – until next Tuesday when it will be resumed.

We regret to say that while the inquiry, as given above, was going on, the other man (Elliott), most seriously injured, was laid dead in the Infirmary. The other two men, still at the Infirmary, are progressing towards recovery.

(Leeds Times, Saturday 7th November 1874

.jpg)

Photo: Phill Davison

The adjourned inquest on the body of Thomas Coates, who was killed on the 4th inst by falling down a shaft at Clayton Tunnel, on the works of the new Great Northern line from Bradford to Halifax, was resumed at the Royal Hotel, Clayton, yesterday, before Mr William Barstow, Coroner.

Edward Keats, the engine driver on the night shift, was the first witness called. He said he was certain that it was Taylor, the other driver, and not himself, who drew up the skep when it went over the pulley. After lowering the skep on to the trolly for the men to get into, witness never meddled with the engine. He saw Taylor on the seat.

William Francis Taylor was then called, and he stated that when he went into the engine-house he and Keats compared watches, and it then wanted five or six minutes to six o’clock. The engine was then standing. Witness turned away to put his dinner into the cupboard and take off his jacket when he heard a signal, but he could not say whether it was to pull up or to lower. When he turned around again, Keats was on the driver’s seat. Witness went towards Keats and told him it was getting near six o’clock and he had better come away. Keats got off the seat, leaving the engine in motion, but before witness could get on the seat he heard the shouting outside and saw the rope on the drum coming slack. He immediately reversed the engine and ran out to see what was the matter. There were two marks on the rope, exactly alike, one to show where the skep was at the bottom, and the other to show where it was at the top. These marks came to just the same place on the drum, and Keats did not tell him whether the skep was at the bottom or at the top, as he ought to have done. It was quite dark and he could not see the skep, but he might have counted the “laps” of the rope on the drum if there had been time. Keats raised the men off the trolly. Witness never turned the steam on at all, as the engine was running when he went to it. Witness had been an engine driver for twenty-eight years.

After some deliberation twelve of the fourteen jurymen returned a verdict of “Manslaughter against William Francis Taylor.”

Bradford Observer, Wednesday 11th November 1874